Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBy 1961, Joan Baez, the dark-haired waif who had captured the spotlight at the first Newport Folk Festival just two years earlier, was folk music's virginal superstar, leading the coffeehouse culture of a new American generation. And an unknown, unwashed, Woody Guthrie—worshiping kid from the Minnesota suburbs named Bob Dylan had just arrived in Greenwich Village. In an excerpt from his forthcoming book, Positively 4th Street, DAVID HAJDU recalls the prickly beginnings of the Baez-Dylan relationship, the strange symbiosis between her voice and his music, and the triumphant, magical appearance at Freebody Park that made musical history

May 2001 David HajduBy 1961, Joan Baez, the dark-haired waif who had captured the spotlight at the first Newport Folk Festival just two years earlier, was folk music's virginal superstar, leading the coffeehouse culture of a new American generation. And an unknown, unwashed, Woody Guthrie—worshiping kid from the Minnesota suburbs named Bob Dylan had just arrived in Greenwich Village. In an excerpt from his forthcoming book, Positively 4th Street, DAVID HAJDU recalls the prickly beginnings of the Baez-Dylan relationship, the strange symbiosis between her voice and his music, and the triumphant, magical appearance at Freebody Park that made musical history

May 2001 David HajduFolk music had begun rumbling across America in the late 1950s. Small festivals devoted to folk were sprouting up on college campuses. Hoping to capitalize on the trend were three savvy entrepreneurs: tobacco magnate Louis Lorillard, would-be folk mogul Albert Grossman, and George Wein, the Boston impresario already successful with the Newport Jazz Festival. The partners put together the Newport Folk Festival, a two-day program of concerts and workshops in July of 1959. The setting was a minor-league ballpark on the Rhode Island seacoast surrounded by the holiday mansions of Gilded Age barons. The performers would include Pete Seeger, the Kingston Trio, bluegrass banjo master Earl Scruggs, the blues duo Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, and the rousing folksinger Bob Gibson. In turn, Gibson had invited an 18-year-old upstart to come join him onstage for a couple of duets. Her name was Joan Baez.

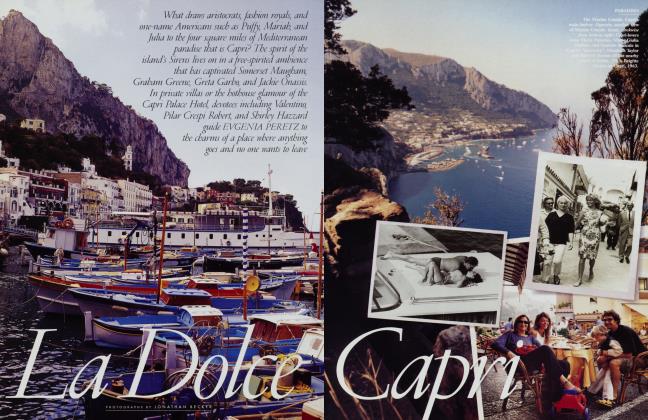

Newport had acquired a reputation as a venue where musical careers could suddenly catch fire. "Folk was becoming the big thing," George Wein remembered, "and Newport was the place to be." A mostly college-age audience of some 13,000 attended opening day, seemingly undaunted by intermittent rains.

"Joan [Baez] stood right by the stage entrance," said Wein, "and she was in bare feet, and she was there the whole time. She got to see and talk to every folk performer. She stayed there all day and night and danced during the music." It was not yet certain that she would get to do any other performing; although Bob Gibson had invited her to sing with him, he needed to square the plan with Oscar Brand, the festival's master of ceremonies. "Bobby Gibson took me aside," Brand recalled, "and he said, 'Listen, there is this girl. She is very popular in Boston. I would like to let her take part of my time.' And I didn't really think it was a great idea. First of all, it was a terrible rainy day, and we were running over. And when he came over with her, she was drenched. Her hair was wringing wet. She was not wearing shoes, and her feet were covered with mud. Bobby said, 'Listen, I will work with her. I won't leave her alone.' And I said, 'O.K., what the hell,' if he was giving up his own time. It was a very loose program."

Hedging her bet on Gibson, meanwhile, Joan asked several other performers if she could sing with them. Robert J. Lurtsema, a radio journalist for WBCN in Boston, watched backstage as she approached the banjo player Earl Scruggs. "He said no, and she moved on to the next guy who was going to be singing," recalled Lurtsema. "She wasn't leaving anything to chance."

Gibson began his set early on Sunday evening, singing and playing the 12-string guitar. He wore a gray sports jacket and a tie, and he sang exuberantly. The audience cheered him on with obvious delight. The rain had stopped, and a mist wafted through the stage light as he paused to tune his guitar and announced, "Now, I want to sing 'Virgin Mary Had One Son.' There is a young lady from Boston whom I have asked to do it with me." Joan Baez strode out briskly in a long-sleeved red dress. She stood alongside Gibson, her hands dropped to her sides. They sang two verses together, and Gibson backed away from the microphone. Joan stepped forward, straight-backed, and sang full-voice:

Some call him David

Think I'll call him 'Manuel

Oh, Oh, think I'll call him 'Manuel

Oh, Oh, I think I'll call him 'Manuel

Glory be to the newborn king.

Oscar Brand had brought his two-year-old son, Eric, to the festival and let him sleep on a couple of chairs offstage. "She sang with such a powerful voice that she woke him up," recalled Brand. "She woke everybody up all the way to Boston." As a follow-up, Gibson, seasoned in stagecraft, chose "Jordan River," a rousing, up-tempo gospel number; Joan let loose on the chorus, Odetta-style, and the crowd erupted in exhilaration. "The audience went crazy-mob psychology and great theater in perfect synchronicity," remembered Greenwich Village folksinger Dave Van Ronk. "Newport absolutely exploded." In the performance of two spirituals, Joan Baez made an evangelical debut.

"You have to understand this in its totality," explained Oscar Brand. "It was the whole atmosphere. The audience was surprised to see her—nobody said she was going to be there. It had been raining. Her hair was stringing down her face. And she stood there very, very simply, and the intensity with which she performed in front of that audience of thousands was just tremendous. It was like she had an aura around her."

In Guthrie, Bob found an image—the hard-travelin’ loner with a guitar . . . easy with women, and surely doomed.

Gibson, though delighted for Joan, declined to take credit for the effect of her performance. "If I hadn't 'introduced' Joan Baez, someone else would have," he wrote in his memoir, I Come for to Sing. "It was like 'discovering' the Grand Canyon. ... Do you think that girl was going to stay unknown in Cambridge?"

"There was no question that she had exactly what the young, new audience was looking for," said Jac Holzman, founder of Elektra Records. "When they came together, it was like a match and stick of TNT." After hearing her sing, Holzman went backstage, eager to sign her to his label, but he never saw her; she was lost in a mob of admirers.

Released in October 1960, the debut album Joan Baez, on the Vanguard label, found an audience first among responsive critics. Robert Shelton raved in The New York Times: "This disk sends one scurrying to the thesaurus for superlatives. It represents one of those beautiful folk performances that one could give to the most conservatory-oriented listener, yet at the same time commands the respect of the most tradition-directed auditor_At the age of only 20, Miss Baez has truly arrived."

There was some prescience in Shelton's hyperbole; as a recording artist, Joan Baez quickly attracted a national following, increasing the prominence of folk in the process. Her album made the Billboard chart and stayed there for 140 weeks. Like all hits, this one was a beneficiary of timing: Joan was an exquisite reflection of her generation's self-image at the cusp of the 1950s and 1960s. How many children of the Cold War sat on the floor next to their record players, listening to Joan Baez murmur of fate, helplessness, and death, thinking, Yeah—they're all my trials, too?

"It was a combination of things," explained Sam Charters, the folk historian and musician. "The absolute clarity, the purity, of her ballad singing and also a distinct earthiness. On record, whatever sex appeal she had in person dissipated. That record was utterly devoid of sex appeal. A few years earlier, no one would have imagined that formula succeeding."

Joan herself was impressed. "Based on everything I had been led to believe about the music business, I could only go so far, because my image was [one] of innocence and purity," she said. "I was not about to change it, because I took that image very seriously, to the point of being obnoxious. I remember thinking, when people compared me and my image to the Virgin Mary, That sounds good to me. Hey—that took her pretty far."

The first hit record by a woman of her generation in the folk idiom—and a bestseller with virtually no advertising, promotion, or "tour support"—Joan Baez was the talk of the coffeehouses. For young women, Joan's ascetic grace and brooding musical persona served as an antidote to the era's sexualized, glamorized formula for feminine celebrity. Thin, dark, strong, smart, virtuous, she was the negative image of Marilyn Monroe—and yet, she too was young and attractive to men. "Girls were just knocked out by her, because she had this waif-gypsy image," said folksinger Barbara Dane. "She seemed like somebody who was absolutely free and in charge of herself, even though she was young. With the bare feet and the straight hair, she looked like this creature who could do her own thing. And that sad music—all the girls who were miserable with their lot in life were dying to cry along with her. Young women were absolutely starved for and ready for an example of somebody like themselves who could dominate the stage and be a different kind of woman up there and also have the guys interested."

To some men, at least, Joan's virginal quiescence gave her reverse-psychology sex appeal; like Doris Day, Joan Baez was a vicarious challenge to would-be predators. "Her whole image—and everything she sang in the early days—drove the men crazy," said actor and singer Jack Landron, who, as Jackie Washington, performed extensively in Cambridge. "The songs were never straight-across 'I love you—we're going to get together and fuck our brains out.' It was always 'I never will marry.' And she looked sad, the hair hung down, and the fellows were thinking, I can make it right for you. She loved us collectively. We loved her one by one. She knew it, and that's the way it worked." Indeed, Joan said she enjoyed the sexual gamesmanship. "I was the virgin princess," she explained. "They wanted to sleep with me, and I could sleep with them if I wanted to. So I didn't have to do it with any of them. It's called control."

Within the record industry, Joan Baez established a new standard. "I had to get my own Baez," said Elektra's Jac Holzman. "I'm quite sure every label in town felt that way." At Columbia, Joan's chart success prompted an especially competitive reaction. "The first thing I wanted was [to know] why didn't we get her," said Columbia executive David Kapralik. He ordered his staff, "The message here is that the kids want this kind of music. Someone else [out there] has just as much to offer. Find her, and let's sign her."

As the sound of Joan Baez spread from Cambridge to Newport to Monterey, young folksingers like her played in coffeehouses and clubs all around the country. The epicenter of this folk boom was New rk's Greenwich Village.

A fabled bohemia since Edgar Allan Poe and Walt Whitman squabbled in its basement drinking halls, the Village had long been infamously tolerant of cultural adventurism. A tradition of folksinging in Washington Square Park, the eight-block town square of Greenwich Village, began in 1945, when a professional printer named George Margolin started strumming a guitar and singing folk songs near the park fountain; Margolin evidently attracted a following and inspired imitators, whose numbers multiplied exponentially. By 1960 hundreds of young people adorned with various stringed instruments congregated there every weekend.

Julius Zito, a Village baker, said the music carried over four blocks to his shop on Bleecker Street and slowed the rise of his bread on Sundays. An itinerant entrepreneur known as the Pick Man was understood to earn a living selling guitar and banjo picks in the park. "You couldn't turn around without bumping into a guitar," said Lionel Kilberg, a salesman for a Manhattan airfreight company who played washtub bass for a bluegrass group, the Shanty Boys. "In the mid-50s, more and more people from all over the New York area were coming to the park to play. Then more people started coming to hear them play. The next week, the same people who just came to listen would be back, only this time they would have guitars, and they would be playing. More people would be listening to them, and the following week they would have guitars."

"Fariña told him straight, 'All you need to do, man, is start screwing Joan Baez.'"

Like good capitalists in a tourist economy, Greenwich Village shop owners acted quickly to accommodate the thriving folk trade. The first coffeehouses in the district—two spare rooms called Edgar's Hobby and David's—had opened in the late 1940s for the area's Italian population. Their inheritors—more than a dozen places all around the Village with progressively whimsical names such as the Cafe Figaro, the Rienzi, the Caricature, the Cafe Wha?, the Dragon's Den, the Bizarre, the Why Not, and the Hip Bagel—now offered folksinging to the mobs of weekend visitors, including uptown residents who would stroll around the Village, just minutes from their homes, as if it were a resort.

There were also hootenannies all over town, as well as frequent parties given by folk buffs such as Miki Isaacson, whose apartment at One Sheridan Square was essentially a youth hostel. "There was something going on all the time, if you liked the music," said Bob Yellin, the son of a concert violist, who became the banjo player for the bluegrass group the Greenbriar Boys. "It wasn't just folk music like the Weavers. There was blues and old-time music and bluegrass and mountain music, and everything else, nonstop." Even in private gatherings hosted by nonmusicians, folk was a mark of egalitarian chic. "If there was a party in the Village," Brand recalled, "it was 'You bring the folksinger, I'll bring the Negro.'"

One of the scene's first important social centers was Allan Block's Sandal Shop on West 4th Street, opened in 1950 by a self-taught leatherworker from Oshkosh, Wisconsin, who played country-style fiddle. Passersby would hear Block playing "Sally Ann" or "Cumberland Gap" between sandal jobs and wander in. Just 20 feet wide and 40 feet deep, the store had a few pine stools set in front of a shop table with a buffing wheel mounted on the side; on an exposed brick wall, Block had hung some sketches of feet and sandal designs he had made. It was a workspace, rustic and spartan. The smell of leather and glue, the sound of fiddle playing, and the sight of hand tools and pencil drawings worked to attract a public veering away from the regimented commercialism that Midtown Manhattan seemed to represent.

"In the beginning, most people saw sandals as something very European or feminine," said Block. "White men wouldn't buy them at all—only black men. Then, I think, people started relating the idea of exposed feet and natural leather and something handmade with folk music and crafts." By the mid-1950s, Block's shop had become a meeting place for Villagers and tourists interested in folk culture; on Saturdays the store was overrun with musicians jamming, trading songs and stories.

Nearby, the grandly christened Folklore Center became the nexus of the Village folk community almost as soon as it opened in April 1957. "Within about three weeks, it crystallized the scene," said Ralph Lee Smith, a journalist who played the Appalachian dulcimer in jam sessions at the sandal shop. "Izzy Young just walked right into the right place at the right time, and he became an instant crossroads, both in the Village and, quite quickly, nationally." An ebullient anarchist raised in a Jewish ghetto in the Bronx, Israel Young, 29, established the Folklore Center at 110 MacDougal Street, one and a half blocks from Washington Square. The store was essentially an excuse for Young to indulge his own passions— books, folk music, and gossip (he was an obsessive diarist). Young's hangout was a narrow shop with new and used instruments hanging on the walls, and racks for records and publications.

"The first place everybody with the slightest interest in folk immediately went was Izzy ung's Folklore Center," said Oscar Brand. "That was where you caught up on the latest news, speculation, and misinformation. If you stayed more than a minute, someone you knew came in. It was a social center, like an old Eastern European town square, and just as profitable. Izzy was the worst businessman in the world. He sold everything at a discount, if he didn't give it away. If you wanted to sing in a coffeehouse, and you needed a guitar, Izzy would give you one and say you could pay him later. Of course, no one did."

Within the store's cramped quarters, Young held concerts, many of which were the formal debuts of young singers new to the city. "I was a real schmuck," said Young. "I didn't know that I was doing everything wrong. But everybody else was schmuckier than me, because they came in and asked me for my opinion."

In its first years, the Greenwich Village folk scene, much like the one in Cambridge that had nurtured Joan Baez, adhered to the labor theory of value. Pete Seeger had reason to be proud: most musicians sang and played for free in Washington Square and passed a basket for change in the coffeehouses (or "basket houses"). The principal measure of success for the majority of folksingers was peer approval. It was a system virtually untainted by professionalism, until nightclubs such as the Village Gate and the Blue Angel began booking folksingers as well as comedians and bebop combos.

From his crow's nest at the Folklore Center, Izzy Young saw the spread of folk into the terrain of jazz and cocktails in Manhattan nightlife as proof of the music's commercial potential—and an opportunity to expand his own enterprise. "Nightclub owners," said Young, "were giving people folk music and booze and a place to meet other people so they could get laid, instead of sitting there in the afternoon sipping espresso. But they weren't doing it right, because they didn't give a shit about the music. I said, 'Hey, I can do that better than them.'"

Working in partnership with Tom Prendergast, a sharp-dressing ad executive with an interest in folk, Young made a deal with Mike Porco, the owner of a bar and pasta house two blocks east of Washington Square, and set up the first folk-only nightclub in Greenwich Village. Porco was an irrepressible man with a calabrese accent that he thickened and thinned like marinara to suit his needs. With handshakes, the pair agreed that Young and Prendergast would book and pay for the acts, handle all advertising and promotion, and take home what they collected at the door ($1.50 per head, no charge on Mondays); Porco would keep all he made from the sale of drinks and food. "It was a good deal—for me," Porco recalled with a grin.

Izzy Young called the room the Fifth Peg, a banjo reference, although most everyone continued to use the restaurant's old name, Gerde's. It was a cozy place. The walls were covered in a maroon flock-paper design, and the tables had red checked covers. The air was a soup of cigarette smoke, beer, and garlic. Gerde's exuded ascetic integrity. A three-foot-high oak-beam partition separated the bar area, on the left, from the restaurant and performance space, on the right; it was a cultural divide between Porco's old regulars, most of them Italian laborers, and the young Village folkies. The musical link between them—the performers on the right were singing about the working people on the left—seemed lost on both sides. "They tended to tolerate each other with benign amusement, complete ignorance, and fear," said Dave Van Ronk.

In the back by the end of the bar, a narrow door led to a basement, a musty windowless area with two benches where waiters and waitresses changed clothes and musicians warmed up or gathered to play informally. The downstairs, recalled John Herald, the Greenbriar Boys' guitarist and singer, "was unbelievably damp. There was a mysterious gray area all the way in the back that was real dark and dank. You'd be playing the guitar and you'd hear sounds from back there— some people were smoking dope or fucking— and you'd keep playing."

It was at Gerde's, in September of 1961, that folksinger Bob Dylan got his first big break.

Born Robert Allen Zimmerman on May 24, 1941, Bob Dylan was just about four months younger than Joan Baez. Raised in Hibbing, Minnesota—a Mesabi Valley mining town drained of the iron ore that had been its lifeblood—Bob grew up in comfort. His father, Abraham Zimmerman, ran a family business, Micka Electric Co., with his two brothers, while Bob's mother, Beatrice (Beatty) Stone Zimmerman, held a clerical job at Feldman's Department Store. They lived in a two-story, tan stucco house on a corner of a middle-class block; there was a terrace on the second floor and a rec room in the basement.

Bob and his brother, David, five years younger, were part of a big, close Jewish family. (Defensive about his family's relative prosperity, Dylan would later insist, inaccurately, "Where I lived, there aren't any suburbs. There aren't any suburbs, and there's no poor section, and there's no rich section. ... There's no wrong side of the tracks and right side of the tracks. As far as I knew, where I lived, nobody had anything that anybody else didn't have, really, and that is the truth.")

Considered a creative and solitary boy, Bob wrote poems, he drew (mainly pencil sketches of cowboys and horses), and he liked music. He listened to hillbilly radio and what rhythm and blues he could find in local record stores, and he taught himself how to play elementary chords on the family's Gulbransen spinet piano. In his teens, Bob was not rebellious so much as absorbed with the idea of rebellion. He went to the Lybba theater (built by Bob's maternal great-grandfather and named for his wife) to watch Rebel Without a Cause at least four times, according to Bill Marinac, one of his friends from Central High. Bob cut out magazine pictures of its tortured young star, James Dean, framed them, and hung them in his bedroom, and he bought a red leather motorcycle jacket like the one Dean wears in the movie. When Bob was 16, his parents bought him a used HarleyDavidson Model 45. He liked to ride his Harley up and down the Hibbing strip, Howard Street, glowering at the road. He was not a strong rider, his friends said; he looked uneasy on the bike and got thrown off once while he was trying a stunt near a passing train.

Bob had started crooning along with the radio at the age of 10 or 11; his childhood idol was Hank Williams. When rock 'n' roll emerged, connected to motorcycles and red leather as a symbol of teen insurrection, Bob became obsessed with the music. He learned how to bang out three-chord songs on the piano well enough to front a string of garage bands: the Shadow Blasters, formed when he was 15 ("We were just the loudest band around," Bob said); the Golden Chords; the Satin Tones. Bob wore a pink shirt and a bow tie. For the Rock Boppers, which Bob organized in the summer of 1958, he adopted a stage name, Elston Gunn. (Elston is an echo of Elvis, obviously; Peter Gunn, a television drama about a hipster detective, first aired that year and had a driving, jazzy theme song that became the source for two hit singles.)

On a 1958 home recording made by his buddy John Bucklen, Bob can be heard playing, singing, and raving about rhythm and blues in adolescent rapture. Asked what kind of music is the best, he blurts, "Rhythm and blues! Rhythm and blues is something that you can't quite explain—see? When you hear a good rhythm-and-blues song, chills go up your spine. You wanna cry when you hear one of those songs." His piano work was a functional approximation of the Little Richard style of blocking major chords, and his voice was sweet and buoyant-something like Buddy Holly's.

A big Holly fan, Bob went to see him perform at the Duluth Armory on January 31, 1959; when Holly died at 22 in a small-plane crash three days later, he joined Hank Williams (who had died en route to an engagement when he was 29) and James Dean (killed at 24) as the third of Bob's heroes to be immortalized by a premature death while on the road. Bob had "a preoccupation with death, out of Hank Williams," his brother said; when Dean died, "Bobby's whole world crashed in," and after Holly's death, "Bobby just went into mourning."

By September 1959, when Robert Zimmerman, then 18, entered the University of Minnesota and joined Sigma Alpha Mu, the Jewish fraternity, rock 'n' roll had done nothing to keep up with its maturing fans. Indeed, during the four years since the first major rock hit, "(We're Gonna) Rock Around the Clock," the music had not merely stagnated but regressed, neutered by record companies to suit the 13 ^-year-old girls they had identified as their most profitable market. Many of the genre's charismatically threatening founders were gone— Elvis Presley drafted, Jerry Lee Lewis and Chuck Berry banished because of sex scandals, Little Richard retired from music (temporarily) to become a minister—and replaced by nice pretty-boys such as Ricky Nelson, Frankie Avalon, and Bobby Rydell. For college students in Minneapolis, just as in Cambridge or New York, rock 'n' roll was a happy memory you left at home with your skates. The music of preference at the U. of M., especially in the artsy off-campus area called Dinkytown, was folk.

When Bob started performing publicly in Dinkytown his freshman year, he was strumming a flattop Gibson acoustic. "Elston" had gone the way of Elvis, Jerry Lee, and the other figures of his teenage dreams. He replaced his motorcycle jacket with a dirty gray tweed sport coat from the Salvation Army and let his hair dangle, uncombed. Bob was a folksinger now. His small but fast-growing repertoire—rural blues and rhythmic, gospel-tinged material he picked up from Odetta records, as well as folk standards—hinted at his past musical identity while he began to craft a new one.

By his second semester, Bob had moved out of the frat house to live with a shifting assortment of fellow artists and bohemians above Gray's Drugstore in Dinkytown, and he was appearing regularly at the local coffeehouse, the Ten O'clock Scholar. The Scholar was a dark, narrow storefront with walls painted flat black and a plate-glass window that faced the street. Sometimes the owner, David Lee, taped a sign on the glass that read, BOB DILLON. Like Gunn, Bob's latest alias was the name of a TV character: Matt Dillon, the stolid marshal of Dodge City portrayed by James Arness on Gunsmoke (the most popular show that year); he had shifted the dramatic milieu from the modern city to the Old West, befitting the young musician's transition from "Buzz Buzz Buzz" to "Muleskinner Blues."

"He listened to everybody, and he had an incredible ability to take things in and absorb them and put them right back out there like they had always been a part of him," said "Spider" John Koerner, a blues guitarist and singer who showed Bob dozens of songs in Koerner's Dinkytown apartment. Beginning in February 1960, the duo of Spider and Dillon appeared often at the Scholar. They sang, among other songs, Lerner and Loewe's "They Call the Wind Maria," from Broadway's Paint Your Wagon.

It was early autumn 1960 when Bob, now spelling his name Dylan ("because it looked better"), began to present a full-on musical persona, although that persona was not his own. An acquaintance had lent him Woody Guthrie's 1943 memoir, Bound for Glory—an epiphany. Bob appeared instantly and wholly consumed by idol worship; he had the book in hand for several weeks, poring over it, again and again. While he had already known about Guthrie and been performing a handful of his songs, including "This Land Is Your Land," Guthrie's music evidently had never struck Bob as deeply as his picaresque tales of life on the road. In Guthrie, Bob found more than a genre of music, a body of work, or a performance style: he found an image—the hardtravelin' loner with a guitar and a way with words, the outsider the insiders envied, easy with women, and surely doomed. An amalgam of his heroes, Dylan's Guthrie was Hank Williams, James Dean, and Buddy Holly—a literate folksinger with a rock 'n' roll attitude.

"He's the greatest holiest godliest one in the world," Bob said of Guthrie—a "genius genius genius genius."

Examining his Guthrie fixation several years later, Dylan explained, "Woody turned me on romantically. As far as digging his talent and what he could do, in all honesty, I would just have to laugh at it [now]_I'm not putting him down. I'm not copping out on my attraction to him and his influence on me. What drew me to [him] was that, hearing his voice, I could tell he was very lonesome, very alone, and very lost out in his time. That's why I dug him. Like a suicidal case or something. It was like an adolescent thing—when you need somebody to latch onto, you reach out and latch onto them."

Guthrie's footprints provided Dylan with a path. He dropped out of school and decided to take to the road. In December 1960, Bob told friends he had telephoned his ailing hero at Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital in northeastern New Jersey and had arranged to visit him there. He headed east by bus. In Madison, Wisconsin, he met a young political activist, Fred Underhill, who was about to drive to New York; Bob went with him. They arrived in Manhattan on January 24, 1961. The weather was as cold as the North Country—14 degrees with nine inches of snow in the streets. Undeterred, Bob and Underhill trudged to the coffeehouses. At the Cafe Wha?, each was allowed to sing a few songs.

After that, Dylan rarely left the Village. "It was like Dylan was in all the places all the time," said John Herald. "u couldn't escape him." He played somewhere—the back of the Folklore Center, the Gaslight, the Commons, the Lion's Head, Mills Tavern—virtually every night for basket change or $10 or $20 from a generous manager, sleeping on couches and floors provided by hospitable folk buffs, as Guthrie had during his years on the road. (Eventually he found a one-bedroom railroad flat at 161 West 4th Street for $80 a month.)

Dylan's appearance and manner, onstage and off, were vintage Guthrie. Dylan paid regular visits to his idol, who was often hospital-bound. "Man, I could whip anybody—I was at the high point of my life from seein' Woody," he crowed, and the more time Dylan spent with Guthrie, the more the acolyte seemed to resemble the debilitated master. "I was visiting Woody at that time also," said John Cohen, of the New Lost City Ramblers. "I had known Woody maybe eight years by then, and you could see all that jerky stuff starting to happen in his body. And then when Bob stood up to the microphone and started jerking around, tilting his head this way, and making these moves—I'd never seen anything like that except in Woody. When I first saw him, I said, 'Oh, my God, he's mimicking Woody's disease.'"

Dylan was 19 now and becoming known around the Village. But his first major work of imagination—his own persona— took shape slowly. "You could not ask him personal questions," said John Herald. "He'd always joke, or he'd tell you something like he used to be a miner—something like that. If you'd ask about his parents, he'd say he had none, or he'd change the subject, or he'd put you on." ("I shucked everybody when I came to New York," he later admitted. "I played cute.")

For those privileged few to whom he opened up, Dylan mustered a parade of colorful fantasies: he was an orphan, born in Chicago or raised in a New Mexico orphanage or in various foster homes; his Semitic features were the mark of Sioux blood in the family; one of his uncles was a gambler, another a thief; he had lived in Oklahoma, Iowa, South Dakota, North Dakota, Kansas, and on the Mississippi River; he had joined a carnival at age 13 and traveled with it around the Southwest; he had played the piano on Elvis Presley's early records. If an acquaintance said something that touched upon Bob's childhood or background—"Did you ever have to sing in church?"—he would snap back, "Dig yourself."

Entertainers have always changed their names and adopted professional images. Indeed, transformation has always been part of the American idea: in the New World, anyone can become a new person. The irony of Robert Zimmerman's metamorphosis lies in the application of so much artifice in the name of truth and authenticity. The folk movement propagated an aesthetic of veracity. It ostensibly celebrated the rural and the natural, the untrained, the unspoiled—the pure. Popular and easy to learn, folk music happened to attract an ambitious, middle-class college kid from the suburbs. It would accommodate him and his ambitions, no matter who he really was, as long as he could create the illusion of artlessness, and Bob did so giftedly. As the cowboy singer and sculptor Harry Jackson told folksinger Gil Turner when he saw the young Dylan perform, "He's so goddamned real, it's unbelievable."

He performed in work clothes—frayed blue denim pants, overworn tan boots, and stained khaki shirts, sometimes dressed up with a brown suede vest or a gray wool scarf—although his body appeared to have endured little hard labor. Pallid and soft, he seemed childlike, almost feminine. What conferred the impression of a life lived hard was his filth. "He looked like he could really use some help around the house," said Terri Thai, an artists' manager. "He looked totally helpless." Bob gave the appearance of being just about the shyest, quietest folkie performing in the Village. He lowered his head and watched his right hand strum as he sang, and when he did look out at the audience, he had a lost look in his eyes. This was largely because he didn't wear his glasses when he played and could see only a few feet without them.

The effect was magnetic. "He in a sense was not a communicator," said Theodore Bikel, the Vienna-born actor and folksinger. "\bu had to come to him all the way. He didn't say, 'It's nice to be here.' He didn't reach out to touch you. You had to come to where he was." Nearly half his usual set was comprised of tunes either written by Guthrie or indebted to him, including some of the first songs Dylan wrote himself—a handful of Guthrie-style "talking blues" numbers and the poignant ballad "Song to Woody." Bob murmured the words in a raw Dust Bowl twang. Between songs, he fidgeted with a funny corduroy seaman's cap he wore everywhere; a few times a night he would pull it off, look at it or lay it on a knee for a moment, then tug it back on. He often started telling a story, somehow connected to a song, presumably, only to drift off in the midst of a thought or puff a bit on his harmonica. The audience, uncertain of what he was doing, watched ever more closely to find out.

Offstage he was even more agitated. Recalling Dylan socially—sipping red wine at Gerde's or playing chess at the Kettle of Fish—his Greenwich Village friends recited a litany of nervous tics: he tapped his feet, one knee bobbed, his head darted back and forth, he scratched, he wiggled in his seat. "Dylan was always hopped-up, you know—I don't mean high, necessarily, [but] hoppedup," said John Herald.

"To put it frankly, he was a nervous wreck," remembered Oscar Brand. "He came on my radio show, and he said nothing but lies about his life. Naturally, he was nervous all the time. He was living with these enormous lies. Here he was, a kid from Minnesota, and he came here to a climate where a number of people were already quite seasoned. He was afraid he couldn't compete and afraid he wasn't good enough, so he lied."

Like many performers in the coffeehouses, Dylan had little difficulty attracting the opposite sex. His public image of unwashed timidity also proved a Freudian advantage. "He was like a hopeless little boy," said Barbara Dane. "All the women wanted to mother him. I think he knew that very well and really worked it." Uncommitted after a couple of flings in New York, he sat with blues singer Mark Spoelstra in a Village nightspot early one morning, talking about romance. "We were pouring our hearts out about girlfriends and how hard it was to find the right one," said Spoelstra. "I told him about the one I dated back in California that I still had a crush on. 'I went out with this girl Joan, and she was wild. Man, she was beautiful and real talented.' I told how we went to that dance, and we were slow-dancing, and I was really into it and loving being with her and holding her, and she started to sing at the top of her lungs while I had my arms around her. Joan Baez. He didn't seem to recognize the name, or he didn't show it if he did. I said, 'She could kill with that voice. Man. And she has this little sister. One time I picked them up, and I drove with her little sister on my lap. I wish she'd been a few years older. I guess she is, now.'"

Dylan knew who Baez was; he was just indifferent to her music. "Her voice goes through me. She's O.K.," he said, according to the notes of a conversation with Bob that Izzy Young logged in his diary a few weeks later. At the same time, he followed her career with interest. "Most of her stuff did not appeal to him at all," said John Herald. "There's no roots in it—no blues, no gospel, no jazz. He was interested in her successhow she got to be so famous."

They met on April 10, 1961. It was a Monday, "hoot night" at Gerde's, and Joan and her kid sister, Mimi, were in New York with their friend John Stein. He had driven them from Boston in his hearse so they could be in Washington Square to protest a measure meant to restrict folksinging in the park. Most of the Village folk community, energized by the demonstrations, gathered at Gerde's Folk City in high spirits. Virtually every singer in town performed two or three songs in competitive Village camaraderie: Doc Watson, Gil Turner, Dave Van Ronk, Mark Spoelstra, Bob, and Joan.

When Dylan sang a couple of Guthrie songs, Joan was impressed. "He had that silly cap on, and he seemed like such a little boy," she said. "But he was a joy to experience. He was captivating. He made me smile." Joan rose to take the stage at the end of the night, the finale. As she sang, Dylan pulled a chair alongside John Stein. "He tugged my sleeve a lot while she was playing," said Stein. "Bobby was very bouncy and twitchy and cute—he was sort of an elf and cute, and he seemed younger than the rest of us, although we were all about the same age. He said to me, 'Hey, man, I wrote a song, and I want Joanie to hear it.'"

By the time Joan finished, it was nearly two A.M. Stein escorted the Baez sisters out the door, and Bob sprang up to follow them—so quickly that he left his guitar behind. On the sidewalk, Bob asked if he could play a song for Joan. She said "Of course" and took her Gibson from its case for him. Bob dropped his left knee onto the pavement and balanced Joan's guitar on his right leg. He seemed certain to tip over while he was singing, "Hey, hey, Woody Guthrie, I wrote you a song ..." Joan, Mimi, and Stein looked down attentively. "It was like Bobby's little command performance," said Stein. "Joanie said she liked it very much, thank you, and Bobby said, 'Ya can sing it if you wanna.'"

The hour being late and the night being unseasonably chilly and damp, Joan excused the group. Bob turned to Mimi, as she recalled, and said, "Hey, do you want to go to a party with me?" Joan answered for her, "No—she can't." She was too young, Joan snapped, and it was already past her bedtime. "It was a little weird that he was hitting on me," said Mimi. "Joanie was very upset." As they rode uptown, Joan fumed. "I don't want you to see him or talk to him ever again," she instructed her sister.

The next day Dylan started telling his friends that Joan Baez wanted to record "Song to Woody." But he wasn't going to give her the permission, he said, because Guthrie didn't like her, and Bob wanted to record the song himself.

In the summer of 1961, Albert Grossman, the ever angling music impresario, came to Gerde's for lunch one day, a rare afternoon intrusion upon the neighborhood laborers by one of the night people. Grossman, a nightclub owner from Chicago, had come to New York and quickly made his name as an aggressive manager of folk talent, and had introduced Joan Baez to Maynard Solomon of Vanguard. In negotiations, Grossman exuded a menacing charm; around Greenwich Village, his nickname was "the floating Buddha."

That afternoon, Grossman ordered the most expensive dish on the menu (breaded veal cutlet, $6) and, during the meal, quietly picked up $100 of the bill for the liquor delivery that happened to arrive. Owner Mike Porco would later insist that Grossman's largesse had no bearing on the fact that Porco would promptly book Bob Dylan-soon to be Grossman's client—for a twoweek run. ("Nobody had to tell me about Bobby," said Porco. "It was me—I gave him his start.")

Grossman, nonetheless, confided in Porco that he had privileged information: Robert Shelton was interested in giving Dylan "a big write-up" in The New York Times, Porco recalled, "and this would be a big thing for me. I told him, 'Good, because I was planning to bring in Bobby for a couple of weeks.'"

It seems possible, though not certain, that Grossman also invested a second hundred to help launch Bob Dylan's career. Porco said he understood that the Times's Shelton—to help defray the cost of coming to see Dylan—had received the same amount as Porco's liquor distributor. Many insiders had heard that Shelton wrote liner notes under pseudonyms to dodge the Times's editorialethics guidelines. By the end of September, the coffeehouses were humming with rumors that Grossman, in fact, had become one of Shelton's freelance employers. Then again, all that talk might have been envy.

On the evening of Tuesday, September 26, a clear, brisk autumn night, Bob Dylan began a two-week engagement at Folk City as the opening act for the Greenbriar Boys. Everyone on the bill had heard that Shelton had promised to review the show. Dylan was frenzied. "Oh, it was a big deal to him," said John Herald. "He was a guy at the Gaslight until that. He asked everybody what he should wear that night, what he should sing. He was excited." He decided on a blue dress shirt, properly unpressed and frayed; a tie, an old foulard that had a brown pattern or coffee stains; a charcoal sweater-vest; khakis; and, as always, his little sailor's cap. For his first set, he chose songs darker and more weathered than his outfit, among them a couple of bleak Guthrie tunes, including "Hard Travelin'." The dominant themes were woe and despair: the world can be cruel to its children, particularly to Bob Dylan. While tuning his guitar to an open chord to play the blues lament "This Life Is Killing Me," he announced, "Here's a song suitable to the occasion."

Dylan's performing style, as it had come together over the past months, was of a piece with his appearance and his material: refined asperity. His guitar playing was erratic; the beat slowed and sped, frets buzzed, dead strings thumped. When a simple minor chord, perfectly executed, rang for a moment, it would seem a kind of miracle. He used the harmonica to produce battlefield sound effects—explosions, rebel yells, and death groans tangentially related to the notes of the musical scale. His voice was rawer still, a pinched mountain holler; melodies came out in nasal moans or growls—at a dramatic point, a yelp. If he wanted, though, he could murmur in a fragile voice of startling beauty, and he would relieve the melancholy with bits of Chaplin-esque physical business. Like Joan Baez, only more so, Dylan seemed to embody the rising generation's rejection of prettifying artifice.

Although the Greenbriar Boys were the headliners, Shelton interviewed Dylan, whom he knew only casually, in the club's kitchen between sets. Dylan grabbed "facts" from the air as if they were Gerde's mascot flies: he had been a farmhand; he had run a steam shovel; he had cleaned ponies; he had played piano for Gene Vincent in Nashville; he had learned his songs straight from their creators, Mance Lipscomb, Blind Lemon Jefferson, and somebody named Wigglefoot, in his ramblin' days. Still talking when the Greenbriar Boys came onstage, Dylan and Shelton moved to a table and continued the interview while the trio played.

Robert Shelton's review was published in the Times on Friday, September 29, under a three-column headline: BOB DYLAN: A DISTINCTIVE STYLIST. Beneath it there was a photo of the singer in his hat and tie. "A bright new face in folk music is appearing at Gerde's Folk City," Shelton began, adding:

Although only 20 years old, Bob Dylan is one of the most distinctive stylists to play in a Manhattan cabaret in months.... There is no doubt that he is bursting at the seams with talent_If not for every taste, his musicmaking has the mark of originality and inspiration, all the more noteworthy for his youth. Mr. Dylan is vague about his antecedents and birthplace, but it matters less where he has been than where he is going, and that would seem to be straight up.

September 29 was also the day Dylan was supposed to play backup on a new album by Carolyn Hester, the most prominent female folksinger in the Village. The recording session, at Columbia Records' Studio A on Seventh Avenue and 52nd Street, was unofficially coordinated by her husband, Richard Farina, a writer whose circle of pals included many of Dylan's folkie friends as well as the aspiring novelist Thomas Pynchon.

The session was not going well when Dylan "bounced in," Hester recalled, with a copy of the Times rolled up in his back pocket. He had been carrying it around all morning, waving it at storekeepers through their windows and stopping friends on the sidewalk so they could read it while he watched the expressions on their feces change. At one point, Farina and the album's producer, John Hammond, repaired to the control booth to sort out their differences. And in the course of their discussion, Farina said, he sang Dylan's praises. Farina remembered telling Hammond, "He's not just a harmonica player. When this is all over, you ought to listen to Dylan."

That day, Dylan played harmonica breaks on three Hester numbers, then stayed in the studio to confer with Hammond. "He asked me what I do," Dylan recalled. There is some confusion over related details. Dylan subsequently claimed that Hammondfamed for discovering Count Basie, Billie Holiday, and Lionel Hampton—offered him a record contract there and then on the basis of the Times piece, without having heard him sing. Hammond later claimed he asked Dylan to audition—more likely, although there is no record of an audition in Columbia's logs. In any case, Dylan was soon telling friends that he was going to be recording for John Hammond. "The following day," Farina said, "we were sitting at the Gaslight, and Bob said that he had just been offered a Columbia contract, and he came over and hugged me."

Dylan and Farina frequented Gerde's and the Gaslight that autumn. "They hung around," said Suze Rotolo, Dylan's girlfriend at the time. "They went onstage with a bunch of people and sang a few times. But we didn't think of [Richard] as a musician, even though he did play. I remember them showing each other their writing—to polish, one writer to another. Bobby liked him. They were kindred spirits. He had a lot of respect for him as a writer. Richard came over to the apartment on Fourth Street once with a story he had written, and Bob loved it. He said, 'This is great—it's poetry.' Farina was writing his novel [Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me, published to acclaim five years later], and Bobby was starting to write songs seriously. They helped each other."

Fred Neil, who hung out at the Gaslight with Dylan and Farina around this time, recalled Richard suggesting a unique career idea to Bob. "Farina gave Bob this lecture," said Neil. "'If you want to be a songwriter, man, you'd better find yourself a singer.' u see, Bob and me, we were both writing, but I knew how to sing. Farina told him straight, 'Man, what you need to do, man, is hook up with Joan Baez. She is so square, she isn't in this century. She needs you to bring her into the 20th century, and you need somebody like her to do your songs. She's your ticket, man. All you need to do, man, is start screwing Joan Baez.'"

According to Neil, Dylan jokingly agreed, saying, "That's a good idea—I think I'll do that. But I don't want her singing none of my songs."

Though they crossed paths at Gerde's a couple of times over the next two years, Dylan and Baez wouldn't have their first extended conversation until April 21, 1963, when both attended the weekly hootenanny at Club 47, in Cambridge. At a party after the hoot, Dylan plopped his guitar down on the floor, then caught Joan's eye as he leaned back in a chair. "Hey, how ya doin'?" he said. "Is your sister here?"

Joan said "No" flatly and finished the sentence with a glare that expressed, in essence, and fuck you for asking. (By then, Dylan's friend Richard Farina had moved to Paris, where he had met, and then married, 17-year-old Mimi Baez, over Joan's objections. Four months later Richard and Mimi would repeat the nuptials in California, with Thomas Pynchon as best man.)

Bob abruptly asked, "Wanna hear a song I wrote?"

Dylan nestled his guitar on his lap and began strumming a C chord in three-quarter time. He repeated it until the small room hushed, then he slid into the opening of "With God on Our Side." By the end of the song's nine verses, Joan Baez was no longer indifferent to Bob Dylan or irked by his crush on Mimi. She was startled by the music she heard and fascinated with the fact that that enigma in the filthy jeans had created it. "When I heard him sing 'With God on Our Side,' I took him seriously," said Joan. "I was bowled over. I never thought anything so powerful could come out of that little toad. It was devastating. 'With God on Our Side' is a very mature song. It's a beautiful song. When I heard that, it changed the way I thought of Bob. I realized he was more mature than I had thought. He even looked a little better."

Dylan played a few more of his topical songs, including "The Death of Emmett Till," "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall," and "Masters of War." They astounded Mark Spoelstra, who had not kept up with his old Milage cohort's development as a songwriter, and he could see they seemed to overwhelm Baez. "Joan was not somebody who was easily impressed," said Spoelstra, "and she was not somebody who was ever at a loss for words. She just sat there with her mouth open."

"You like 'em?" Dylan asked.

Baez just nodded, smiling, while Spoelstra and a few other musicians watched in fascination. "It's fair to say [that] I fell under that spell of his," said Joan. "Nobody was writing like that. He was writing exactly what I wanted to hear. It was [as if] he was giving voice to the ideas I wanted to express but didn't know how." Joan had to leave soon; it was after two A.M., and she had an early-morning flight back to California. As it happened, Dylan was supposed to play at the Monterey Folk Festival in a few weeks, he said. She should come and hear him. She could sing something with him, if she wanted to. Joan thanked him and said she liked that idea. She now lived near Monterey. In fact, she said, he was welcome to come to her house and visit while he was in the area. Bob said sure, that sounded cool, and almost smiled.

Having nurtured his charge for two heady years—through one album, a burgeoning songwriting career, and even the occasional acting job—Albert Grossman arranged for Dylan, not yet a household name, to appear on the same stage as Peter, Paul and Mary just as the group's rendition of Dylan's "Blowin' in the Wind" began airing on the radio. (The 45 would become the fastest-moving single, up to that time, in Warner Bros, history.) On May 17, 1963, the trio headlined the opening day of the Monterey Folk Festival; the following evening the bill would include, among others, the Weavers, the New Lost City Ramblers, and Bob Dylan—his first appearance in California. (Ten days later, The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, his second album, would hit record stores.)

Dylan traveled from Los Angeles to Monterey with Victor Maymudes, the founder of L.A.'s pioneering coffeehouse, the Unicom. Then 29 and impressively conversant in liberal politics, Eastern thought, Beat literature, and everything else modish, he kept Dylan company and attended to professional details under Grossman's auspices. "Bob [was] a very internal being," Maymudes recalled. "When we drove, I don't think he said much of anything to anybody. He was always processing." Dylan and Maymudes shared the ride with Jac Holzman of Elektra and Holzman's colleague Jim Dickson; they took turns driving Jim's overridden Ford Falcon, which kept molting parts on Interstate 5, while Bob quietly fingerpicked his guitar in the backseat. "He was very private and withdrawn," Holzman said. "I think he was writing songs while we were talking. I remember wondering if I was going to hear my own conversation in the next song of his."

Joan Baez was waiting for Dylan in Monterey. Taking him up on his offer to sing something with him at the festival, she had learned "With God on Our Side." The two reunited backstage and quickly ran through the song. When it came time for Bob's 15 minutes onstage, Barbara Dane, the festival's host, introduced Dylan as the man who had written Peter, Paul and Mary's new single. Scattered mumbles. He shuffled out and did three of his hardest-hitting protest songs: "Talkin' John Birch Paranoid Blues," "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall," and "Masters of War." Yet the Monterey audience, largely unfamiliar with Dylan's style, responded poorly, talking loudly as he performed. "The rumbling around was that he didn't go over that well," Dane recalled. "People hadn't heard anything quite like that before. I don't think they understood what he was all about."

Then Joan walked out, with no introduction, to murmurs of surprise and eager applause. As Bob began strumming the opening chords of "With God on Our Side," the crowd quieted. Baez, standing alongside him, inched closer to his microphone. She wanted everybody to know, she said, that this young man had something to say. He was singing about important issues, and he was speaking for her and for everyone who wanted a better world.

Dylan began singing, "Oh, my name it is nothin' / My age it means less ... ," and Baez joined in, singing harmony. "I had barely finished memorizing [the song], and the [weather] was very hot," Joan recalled. "There was perspiration running down the small of my back and behind my knees. I was nervous, excited, and exhilarated." Their voices seemed mismatched—salt pork and meringue—but the tension between their styles made their presence together all the more compelling.

They seemed elementally incompatible, Joan with her ethereal tone and tight vibrato, Dylan talk-singing in earthy yelps; together they sounded like Glinda, the Good Witch of the North, and the mayor of the Munchkin City. But they functioned more like a movie couple, Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Joan seemed to soften Bob, and he emboldened her; as the Hollywood fan magazines used to say about Astaire and Rogers, Baez gave Dylan class, and Bob gave Joan sex appeal. Doing harmony with Baez, Dylan sang more melodically, applying himself to hitting the notes (or coming closer than usual), and he used warm, sweet parts of his voice that he had been keeping secret from audiences since singing Buddy Holly songs in high school.

That night in Monterey, they left the stage with 20,000 people cheering.

The following day, Joan and Bob watched the festival's last performers and talked. They strolled the grounds, gorging on hot dogs and laughing at the amateurs in the "song swap" under the concession tent. Bess Hawes, who sang in the "Gospel GetTogether" that evening, saw the pair huddled together, and assumed they were longtime lovers. Although this was essentially their first date, Baez and Dylan appeared intimately attached, and Joan's prominence, especially there on the West Coast, ensured that everyone noticed.

Bob accepted Joan's invitation to visit her house in the Carmel Highlands. She drove him in her Jaguar XKE, and she cooked a pot of stew. He played and sang his songs. They sat on the wide-plank pine floor in the living room, surrounded by windows that restrained encroaching eucalyptus trees on all sides. Dylan taught her the chords to half a dozen or so of his songs and wrote down the lyrics for her. They tried singing most of them together, experimenting with arrangements and harmonies. "It was very exciting but challenging," Joan recalled, "because he never wanted to do the same thing the same way twice."

After a couple of days together, playing music almost constantly, Joan found herself captivated equally by the power of Dylan's music (especially his protest songs) and the alluring frailty of its composer. "I was falling in love," she said. "When I heard those songs, I melted. They were manna from heaven to me, and he was so shy and fragile. I wanted to mother him, and he seemed to want it and need it. He seemed so helpless."

Dylan's feelings toward Joan were unclear. Back in New York, Bob had begun seeing Suze Rotolo again, although their relationship was cooling. Joan could only assume or hope that Bob had affection for her and that perhaps it was growing quietly. "We didn't need to make love," she said. "The music seemed like enough at the time." Like Scheherazade, Dylan may have called upon the muse to postpone something for which he was not quite ready.

Re-invigorated by their musical collaborations, Joan told Bob she had a concert tour of the Northeast coming up and she wanted him to join her on it. She was now singing to audiences of 10,000; she could introduce him to all those people. Bob said, Hey, yeah, cool—and they had a deal. Joan drove him to Monterey so he could catch his ride back to L.A.

After he left, Joan seemed obsessed with Bob Dylan. She walked to her neighbor Cynthia Williams's house, the town square of the Highlands, and announced to the neighborhood that she had discovered a genius. As for Bob, he sat in the back of Dickson's Ford, softly playing his guitar again, and he never mentioned Joan Baez during the seven-hour ride to Los Angeles. Said Jac Holzman, "We didn't even know he stayed with her. He didn't utter her name. He was exactly the same—quietly working on his music. Whatever he was thinking, he was putting into his songs."

The next month, Joan sent an LP to Mimi, who had just graduated from a high-school correspondence course. It was The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. Joan had clipped a note on the sleeve: "My new boyfriend." This seemed to Mimi like a competitive taunt; when they had met Bob at Gerde's, he had flirted with her, not Joan. The record was puzzling, too; if Joan was Bob's girlfriend, who was the cute brunette on the album jacket, walking arm in arm with Dylan through the snow?

If the cover photograph of Dylan and Suze Rotolo on Jones Street the previous winter was out of date, the album fully captured Bob in his most recent incarnation: a socially conscious composer. It included a portfolio of mature original songs (such as "Blowin' in the Wind," "Don't Think Twice, It's All Right," "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall," "Masters of War," "Girl from the North Country"), and it proved to be a thoroughly persuasive declaration of Dylan's seriousness of purpose—ambitious, musically varied and nuanced, and literate, a demonstration of Dylan's ability not only to change but also to grow.

The following month, nine weeks after Joan had joined Bob onstage in Monterey, they reconnected at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival. It was "the peak of the folk boom," said George Wein, who had helped loose Baez upon the world four years earlier. An estimated 47,000 paid attendees overflowed the three-day concert. Seventy acts were scheduled to perform.

Baez was returning to the site of her breakthrough, but she was now taking on the role Bob Gibson had played in 1959. "What I wanted to do was help Bobby [Dylan]," Baez said. Dylan was hardly an unknown; Peter, Paul and Mary had been raving about him in concerts around the country. He was all the talk at Newport. Joan, however, was now such an institution that her influence permeated the festival. When Robert J. Lurtsema approached her near one of the Newport stages to request an interview for WBCN radio, he was told, "I'm sorry, I'm not Joan Baez." He looked closely and realized he was not talking to Joan at all, but to another woman, who had modeled every aspect of her appearance on Baez. Lurtsema glanced around and saw Joan Baezes everywhere.

Bob and Joan opened and closed the festival together. And it would begin a period of collaboration and joint performance that they would reprise a decade later. During those early years, Joan recalled, Bob looked terrified.

"I remember him coming out with his humble attitude," Joan said. "He was really scared, and he couldn't hide it. He would never admit that, but he was scared. So he did his whole shy-little-poet thing."

"She was getting a kick outta having me coming up—baggy elephant me, come up and sing my songs, which nobody had ever heard before," Bob remembered. "And her audience, which are just like pieces of wheat, anyway, man—when they heard my songs, they were just flabbergasted."

"It was exciting for me to bring him out, but it was also a big challenge, because my audience didn't like it," Joan said. "They didn't want this scruffy little guy out there, singing off-key. Some people would heckle him, and I would come out from the wings like a schoolteacher type and scold them— 'You're very lucky to be hearing him,' that kind of thing. 'You'll be hearing more of him. You'll be sorry!'"

Yet over those three days and nights at Newport, Baez and Dylan appeared neither stilted nor hesitant, but magical and triumphant. Together, they helped create one of the pivotal moments in American musical history.

On that first evening of the festival, Dylan performed a brief set of his own, sardined in a ludicrously overpacked bill (Bill Monroe and His Bluegrass Boys, Doc Watson, Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry, Peter, Paul and Mary, and five other acts). Peter Yarrow ended the concert by asking the audience to sing "Blowin' in the Wind" with his trio, and he called a select group of compatriots onstage to join them: Seeger, Theodore Bikel, the Freedom Singers (Rutha Harris, Bernice Johnson, Charles Neblett, and Cordell Hull Reagon), Baez, and Dylan. As an encore, they all locked hands and sang "We Shall Overcome," swaying in time.

The image of this assemblage at Newport would become one of the primary symbols of the 1960s folk revival: the Old Guard joined with the New, the commercial and the Communist, black and white, leading a sea of young people in a sing-along for freedom. "I think of that highlight of the 1963 Newport Folk Festival—that stunning, stirring ringing out of 'We Shall Overcome'— as the apogee of the folk movement," said Theodore Bikel. "There was no point more suffused with hope for the future."

Yet the moment had another dimension. Despite the defiant words the group was singing (a civil-rights anthem adapted from Charles Tindley's early-20th-century spiritual "I'll Overcome Some Day") and the physical posture it adopted (a line of solidarity traditionally employed to resist police), this was as much a crow of triumph as it was a rallying cry. The performers holding hands onstage could well have been singing "We Have Overcome." From the Newport stage on July 28, 1963, Pete Seeger and company were essentially proclaiming the triumph of the political folk diaspora. It had overcome the anti-Communist blacklist, the rise of television, the hit parade, Tin Pan Alley, and rock 'n' roll; it had never been so prominent— indeed, no other music in America was as popular as folk.

On Sunday, Joan Baez closed the final concert of the festival. She wore a simple knee-length white dress that clung to her, and she sounded as stunningly unadorned as she looked. At the conclusion of a set peppered with Dylan songs, including a pointed "Don't Think Twice, It's All Right," she thanked the audience effusively. "Tonight is one of the most beautiful nights I've seen," Joan said with a broad smile. "I'm all up here with it. I feel sort of like exploding." She bounded offstage and came right back with Bob Dylan in tow. He was wearing a short-sleeved khaki work shirt and grimy blue jeans. They sang "With God on Our Side." It was the last song of the festival at Freebody Park, the final impression made upon the 13,000 listeners, the 68 other musicians, and the press. As Robert Shelton and several others wrote in virtually identical words, "Baez, the reigning queen of folk music, had named Dylan the crown prince."

Excerpted from Positively 4th Street, by David Hajdu, to be published in June by Farrar, Straus and Giroux; ©2001 by the author.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now