Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

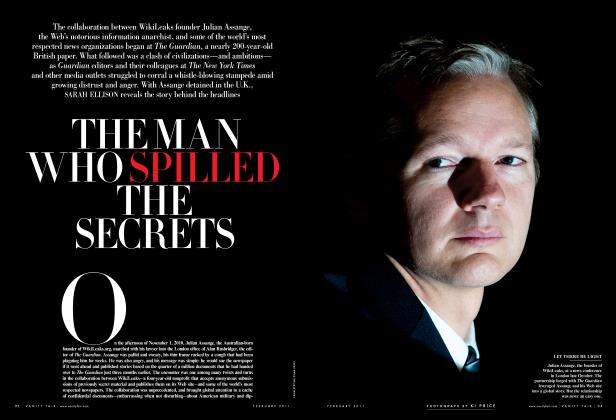

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAs the 100th anniversary of Duke Ellington's birth spawns tributes in more than three dozen cities, the jazz king's life still holds a central mystery: the indefinable bond between Ellington, a notorious Lothario, and composer Billy Strayhorn, whose open homosexuality was rare in its day. DAVID HAJDU, president of the Duke Ellington Society and Strayhorn's biographer, examines a collaboration that began in 1938 with an instantaneous meeting of musical minds and led to such classics as "Take the 'A" Train" and "Satin Doll."

May 1999 David Hajdu Gordon ParksAs the 100th anniversary of Duke Ellington's birth spawns tributes in more than three dozen cities, the jazz king's life still holds a central mystery: the indefinable bond between Ellington, a notorious Lothario, and composer Billy Strayhorn, whose open homosexuality was rare in its day. DAVID HAJDU, president of the Duke Ellington Society and Strayhorn's biographer, examines a collaboration that began in 1938 with an instantaneous meeting of musical minds and led to such classics as "Take the 'A" Train" and "Satin Doll."

May 1999 David Hajdu Gordon ParksSecretly dying of the cancer that would claim him within months, Duke Ellington, sallow and thin, stood before the assembled in Westminster Abbey on October 24, 1973, for the premiere of his third and final Sacred Concert, and a chorus sang the 74-year-old composer's words: "Every man prays in his own language." Publicly, Ellington spent much of his last decade communing with the divine in grand, if unorthodox, devotional performances. Privately, retiring in the hotel rooms that were his home for more than half a century, he used a prayer book. His son, Mercer, later donated one of Ellington's volumes, a 1966 edition of The Catholic Hymnal, to the Smithsonian Institution. When an archivist unpacked it recently, she called me. She had found some photographs tucked between the pages, and she thought I should see one of them before it was filed away, erasing any record of its origin. It's a snapshot of a sweet-faced, bespectacled African-American man, Billy Strayhorn, half dressed, reading a book in bed.

What was Duke Ellington saying, in his own language? Why would one man, reading in solitude, care to look at a picture of another man doing the same? And what might that have to do with the music that is Ellington's legacy?

This April 29 marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Edward Kennedy Ellington, one of the true pioneers of jazz. Duke reigns omnipotently over the cultural landscape, or at least its high ground: Concerts and conferences devoted to Ellington are scheduled at dozens of arts centers and institutions, from New York's Lincoln Center to Ohio's Cuyahoga Community College. A torrent of new Ellington CD collections and reissues will land atop the more than 150 titles in circulation. There will be a nationally syndicated radio series, musical celebrations in three dozen cities, even new ballets in Duke's honor.

Fleetingly, the face in that photograph from Ellington's prayer book shifts in and out of view. In panel discussions, as experts ponder Ellington the Legend, Billy Strayhorn is mentioned with reverence. In out-of-the-way cabarets in Manhattan and Istanbul, vocalist Allan Harris has been performing all-Strayhorn tributes. Filmmaker Irwin Winkler is now casting a screen version of Strayhorn's life. And the credits on virtually every new Ellington CD list William Thomas Strayhorn as composer or co-creator of some of the best-known pieces associated with Duke, including "Take the 'A' Train," "Satin Doll," "Chelsea Bridge," and suites such as "Such Sweet Thunder."

Yet Strayhorn, Ellington's chief collaborator and perhaps the most influential figure in his creative life, is still, somehow, but an ethereal presence. Though their careers are elementally inseparable, the true nature of their collaboration remains virtually unknown—or unspoken. As Strayhorn's biographer, I have explored their three-decade partnership extensively; indeed, some of the interviews quoted herein were gathered for my 1996 book, Lush Life. And the question remains: How to explain a relationship between men of such contrasts? Ellington, tall and commanding, a master jazz innovator who managed his orchestra and his expansive songbook like a small industry, a brilliant scholar of the streets whose regal air and grandiloquence, vaguely ironic, had the charm of an irresistible con game; Strayhorn, tiny, attentive, demure, a consummate composer and arranger, content to remain in Duke's massive shadow, a culture buff who relished New York (as well as Paris, eventually) and developed a taste—and oversize appetite—for high style in food, fashion, and nightlife.

In the section on Strayhorn in his 1973 memoir, Music Is My Mistress, Ellington was, as always, poetically obtuse on the subject: "He was not, as he was often referred to by many, my alter ego. Billy Strayhorn was my right arm, my left arm, all the eyes in the back of my head, my brainwaves in his head, and his in mine."

Many fellow musicians have called theirs a unique case of artistic intimacy. "Ellington's relationship with Strayhorn was one the likes of which I will never see and maybe the world will never see again," says Luther Henderson, the composer and arranger with whom Ellington and Strayhorn crafted many of their most ambitious projects, including several longform works for symphony orchestra. "It was obviously a special relationship. Duke had an enormous love for Billy apart from his work," explains George Avakian, Ellington's longtime producer at Columbia Records. "It was a love affair between the two, as artists," remarked the late trombonist and arranger Billy Byers.

That's the essence of the story, I am convinced: they loved each other. But what kind of love? As Ellington frequently noted, he and Strayhorn abhorred all categories, whether aesthetic, social, racial, or emotional. Moreover, it seems that Duke Ellington, a notorious Lothario, loved Billy Strayhorn more fully and deeply than he loved any woman in his life—excepting his mother and his sister, Ruth. No matter how many scholarly panels we convene, the complexity of their love remains elusive, even in our ostensibly enlightened age.

With a conjurer's regard for the allure of the unknown, Ellington always kept the details of his collaboration with Strayhorn a mystery. "Edward always used to say, 'Don't peek your hole card,'" explained the late Marian Logan, wife of Ellington's friend and doctor, Arthur Logan.

"[Edward] would never answer the question 'Who wrote this? Who did this?'" recalls Teo Macero, the arranger and producer who made several Ellington albums for Columbia. "He'd say, 'Sweetie ... you know, I don't know. Maybe Billy, you know, me ... ' And it would go round and round and round."

"They were like one mind. They were like Clark Kent and Superman."

Ironically enough, when he first met Strayhorn, in 1938, Ellington was hardly in need of a muse. Not even 40 and a bandleader for nearly 20 years, Ellington had proved to be not merely a skillful writer of distinctive popular songs ("Mood Indigo," "Solitude," "Sophisticated Lady") but also a serious composer of more intricate works ("Creole Rhapsody," "Reminiscing in Tempo") which had begun to redefine jazz as a music for the ears as well as the feet, earning due praise from highbrow critics and composers such as Aaron Copland. Ellington, however, recognized Strayhorn's talents as a pianist, composer, lyricist, and arranger when the prodigy, then 23, attended one of Duke's concerts in Pittsburgh. (The pair were introduced backstage by William Augustus "Gus" Greenlee, the charismatic sports impresario, nightclub owner, and presumed racketeer.) Ellington was so taken with Strayhorn's skills that he immediately implored him to write songs for the band, swiftly jotting down directions to his Harlem apartment, subway line and all—scrawls which Strayhorn ingeniously fashioned, within a week or two, into the swing classic "Take the A' Train."

Strayhorn had gone as far as Pittsburgh could take him. Conservatory-trained, he had already composed several sophisticated pieces merging jazz and the classical tradition; played bar piano all around town; led his own jazz trio; arranged for half a dozen local bands (black, white, and mixed); and written songs that would later become jazz standards, including "Something to Live For," "Your Love Has Faded," and his signature piece, "Lush Life." Highly regarded by the few who knew him, Strayhorn lost ground, nonetheless, as a result of two provincial pressures: his trio and his main big-band affiliation, both mixed-race groups, had been forced to dissolve after incidents of prejudice against Strayhorn, because he was African-American; and he was dropped from the best black band in town, because he was gay.

In a drumbeat after they met, Ellington had him move into his apartment on Edgecombe Avenue in Harlem's tony Sugar Hill district, where Strayhorn lived like one of the family with Ellington's girlfriend Mildred Dixon, Duke's only sibling, Ruth, and his son, Mercer. (Ellington was estranged, though never legally separated, from his wife, Edna.) The benefits of their collaboration proved exquisitely mutual: Ellington gained a second set of gifts to help expand his musical palette and take him beyond the big-band idiom into the worlds of the concert stage and the theater; Strayhorn, in turn, now had a world-class vehicle for his music and the freedom to compose without bearing public scrutiny and the risk of rejection for his homosexuality. That Strayhorn would toil largely behind the scenes often contributing anonymously to the ever broadening Ellington canon, worked to the advantage of both.

And that Ellington might not have really required the young man's assistance would quickly become moot; they grew reliant upon each other. "His approval was like going out with your armor on, instead of going out naked," Ellington said of Strayhorn in a 1968 interview. "We had a relationship that nobody else in the world would understand." The composers worked together from 1938 to 1967— often closely, occasionally as a sort of musical tag team, trading portions of pieces in mid-creation.

Wherever in the world his performances took him, Ellington called Strayhorn religiously, writing songs by phone, virtually every night. Their collaborative output includes dozens of jazz masterworks, from songs such as "Day Dream" and "The Star-Crossed Lovers" to extended jazz-orchestra pieces, from the Broadway musical Beggar's Holiday to film scores.

"Our rapport was the closest," wrote Ellington. Indeed, according to photographer Gordon Parks, who spent several days observing Ellington and Strayhorn in 1960, on assignment for Life magazine, "they were like one mind." Preparing for a Los Angeles recording session, the pair shared a small suite at the Chateau Marmont in Hollywood, Parks remembers. Ellington would start writing late in the evening while Strayhorn slept; around two A.M., Strayhorn would awaken and resume composing where Ellington had left off, while Ellington would take Strayhorn's place in bed. "One person would work until he got sleepy," recalls Parks. "They never seemed to be in the room at the same time. They were like Clark Kent and Superman. You wondered if they were really the same person, changing disguises in the bedroom." What's more, Parks says, "they didn't talk about the music. One would just leave it for the other one, and he would pick up as if he had been writing the whole thing himself."

"Billy would sit and stare into his eyes ... and Duke would stare back ... and Billy would go out and write what Duke wanted."

Ruth Ellington described the communication between her brother and Strayhorn as virtually psychic. "I've seen [Strayhorn] walk into Duke's dressing room," she recalled, "and Duke would say, 'Oh, Billy, I want you to finish this thing for me.' Just like that. And Billy would sit and stare into his eyes ... and Duke would stare back, and then Billy would say, 'O.K.' They wouldn't even exchange a word. They'd just look into each other's eyes, and Billy would go out and write what Duke wanted. That's why he and Duke got along so well—because he could look at people and see through them. If he looked at you, he could tell exactly what you were."

Ellington couldn't abide such an intrusion—from anyone other than Strayhorn. "He didn't like anybody who could read his mind," his son, Mercer, remarked. "That's what gave him his strength over people. Pop knew everybody's weakness, but he would never, never—oh, man, never— he'd never let anybody know his. Strayhorn was the only one. He let Strayhorn in the door. That door was locked for everybody else, and I do mean everybody— family, his women ... me, too, before the old man was dying, and I was the only one sitting there."

If Ellington granted his collaborator unique emotional access, the key to it was their music. "Let me tell you the one thing that will explain everything there is to know about Duke Ellington, including that magic between Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn," said a friend of both composers. "Music. That's it. Duke Ellington lived, breathed, ate, and drank music. That's all that really mattered to him—nothing else. That's what he loved. And he loved Billy Strayhorn because they made music together."

Marian Logan, perhaps because she was the wife of a physician, had a more diagnostic view. "Everybody knows Edward had eight million women," she said. "You have that many—and you're never home for any longer than a day every year—and you don't have to get overly close to none of them, and you don't have to worry none about them getting too close to you. The only real partner that man ever had was Billums [Strayhorn]. He called him his 'musical companion,' you know. Strayhorn adored that. [Edward] kept everybody else very far away, built a wall around himself—a big, gold, shiny wall. The only person inside with him in there was Billy Strayhorn. He wouldn't let his own doctor in, believe me.

"Edward had a kind of intimateness with Strayhorn that he never gave his girlfriends, none of them," Logan continued. "He trusted him [because] of the one thing that cut way down deep into him, and that means the music. It's hard to explain what it was. He had a very, very, very deep love for Strayhorn, and Strayhorn obviously loved Duke, too, to work with him like that for all those years. You can call it whatever you want. It had all to do with his music, and I think it was the only kind of love Ellington was truly capable of."

Though artistically plausible, Logan's assessment overlooks paternal love. From the onset of their association, Ellington included Strayhorn in his familial circle—and inserted himself in Strayhorn's; Duke would wire Billy's mother, Lillian, back home in Pittsburgh, on her birthday and Mother's Day. A generation older and far more prominent than his junior partner, Ellington would seem an obvious father figure. Then again, he avoided the obvious in most matters of business, art, and family. "That's the way it probably looks, a father-and-son thing, but it wasn't that simple at all," recalls Lena Horne, Strayhorn's dearest friend and confidante. Horne, who still keeps Strayhorn's portrait on her nightstand, also worked with Ellington and had something of a fling with him once. "Duke didn't want to be anybody's father—hell, no! Not even his own son's, and certainly not Billy's. He wasn't old enough to be a father!" she says with a big laugh. "Duke was young forever—he thought he was, anyway—young and sexual. Listen to his music. He never aged a day, till Billy died."

When Billy Strayhorn, then 51, succumbed to esophageal cancer on May 31, 1967, Ellington, then 68, fought to come to terms with it, while those around him struggled to understand Ellington's reaction. Mercer, who served as road manager for the orchestra at the time, recalled his father as angry and distraught. "He said, 'Why me? Why did this have to happen to me?' Only time I remember him ever saying, 'Fuck it,' he didn't want to play." Shortly after Strayhorn's death, pianist Donald Shirley, a friend of both Ellington's and Strayhorn's, went backstage to see Duke at the end of a performance and found him alone at the piano, head bowed, playing Strayhorn's "Lotus Blossom" over and over.

Ellington's grief was so deep that his publicist, Joe Morgen, circulated what has been considered a fabricated interview with the deceased, reportedly to deflect rumors about the musicians' close relationship. In it, an uncharacteristically tough-talking Strayhorn justifies his bachelorhood by claiming, loopily, that his apartment was too sloppy for any gal to stomach.

"Duke was young forever—young and sexual. Listen to his music He never aged a day till Billy died."

The degree to which the mercurial love between the pair may or may not have seeped past the chalk lines of heterosexual friendship is unknowable, though it proved to be anything but imponderable. As Strayhorn's biographer, and the president of the Duke Ellington Society, I've been asked literally scores of times if their relationship had a homosexual component. In the muted Ellingtonian tradition, I've tried to dodge the question gracefully.

Yes, Strayhorn was gay, and he undoubtedly had a love for Ellington; however, Strayhorn was known as monogamous and appeared wholly devoted to each of his four main companions in turn. Might he have longed for a more amorous involvement with Ellington? Perhaps, some have said. "I think that if Strayhorn could have constructed a relationship with Ellington, then he would have," Mercer told me. (Mercer died at 76 in 1996.) "He loved him that much."

As for Duke, Mercer said—with no hint of spin—he had always simply assumed that his father's bond with Strayhorn, his legendary sexual appetite, and his seemingly boundless sense of adventure likely led to some experimentation with Strayhorn. "I don't know for a fact—I didn't watch them," he said. "I just presumed as much. So did the cats [in the band]. One told me he walked in on them one time. I never pressed the issue. It seemed like a given."

A few of those close to Duke Ellington discussed homosexuality with him directly. According to Sam Shaw, producer of the 1961 film Paris Blues, scored by Ellington and Strayhorn, "Duke talked to me about Billy and the whole subject of homosexuality. In certain [African] tribes, the priests wore blue robes, which were the symbol of their status. They were considered holy, and they were bisexual—part of the African culture. Duke accepted that as part of nature."

Some of Ellington's personal beliefs, feelings, and preferences—including, for instance, his habit of wearing blue clothing—are more than just subjects of gossip because they had a significant effect on what he brought to the public. This year, as innumerable celebrations acknowledge his contributions to 20th-century culture, one accomplishment may go little noted: Duke Ellington accepted, nurtured, supported, and empowered a small, shy gay man whom he loved as a soul mate, and he gave voice to that man's music through his own. There's a sound within the sound we think of as Ellingtonia, and much of it is a world apart from the assertive drive of big-band swing. "Passion Flower," "Lotus Blossom," "A Flower Is a Lovesome Thing," "Minuet in Blues." In dozens of Billy Strayhorn compositions that Ellington performed and recorded with his orchestra, the listener encounters expressions of humanity's subtler shades—a gentleness, a sensitivity, sometimes a sadness, arguably a gay sensibility, there on the jukebox from the same band that played "It Don't Mean a Thing if It Ain't Got That Swing." Though Billy Strayhorn could swing when he wanted (having written Ellington's theme song, "Take the 'A' Train," the leitmotif of the whole swing era), other things meant a thing to him, too. Billy Strayhorn composed eight songs about flowers.

"The music of Duke Ellington is regarded as so great and so important now," notes Kevin McGruder, executive director of the organization Gay Men of African Descent. "To think that some of it is the voice of a gay man making distinctive statements of his own is quite something. It's a real testament to Duke that he embraced Billy Strayhorn the way he did and gave him that outlet. I can't imagine any other bandleader of his time doing that."

During the seven years between Strayhorn's death and Ellington's, of cancer on May 24, 1974, the aging composer turned his attention to God. He created three major works of sacred music and performed them in churches and temples, accompanied by singers, dancers, and a full orchestra. "He started channeling his music and his deep capacity for love toward God," explains the Reverend Janna Steed, a United Methodist theologian now writing a book about Ellington's religious music. "His theology was quite simple. All Duke was saying, basically, is 'God is love, and love is the answer to everything.'"

For reference, he always had his prayer book.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now