Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

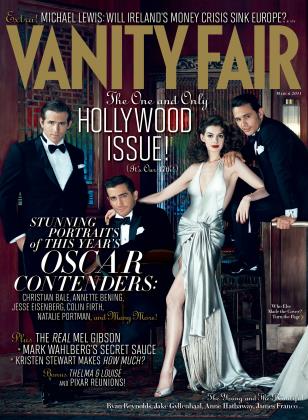

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHow Harvey Got His Groove Back

FOR DETAILS, GO TO VF.COM/CREDITS

BRYAN BURROUGH

After several years in the wilderness, Harvey Weinstein has come roaring back (if a bit less loudly) into the moviemaking sweet spot, winning raves for The King's Speech, The Fighter, and Blue Valentine. But his bitter war with Disney over Miramax, the crushing blow of losing the company (named after his parents) a second time, and his attempt to build a multi-media empire—all have left their scars. BRYAN BURROUGH learns about the darkest hours of a man who, love him or hate him, may be the last true impresario

On a chill Sunday evening last autumn, a select group of powerful New Yorkers filed into a screening room at the Tribeca Grand Hotel. News Corp.'s Rupert Murdoch slouched in an aisle seat with his wife, Wendi, rising just to accept a hug from Katie Couric. Leveragedbuyout king Henry Kravis sat a row in front of them, managing a weak smile as his rival Steve Schwarzman, clad in a battered barn jacket and worn jeans, eased into an adjacent seat. In the back, painter Julian Schnabel kibitzed with Jamie Rubin and Christiane Amanpour, turning in his seat every now and then to whisper with Debra Winger. In a darkened corner the evening's co-hosts, Julianne Moore, Ellen Burstyn, Patricia Clarkson, and Christine Baranski, huddled together.

"[Disney] wont sell to me," Harvey told a friend' "BECAUSE THEY HATE ME. IF ITworked out... it would make them look bad"

By and by the host, Harvey Weinstein, raised a microphone and in a scant seven sentences introduced the film's star, Colin Firth, who introduced the movie, The King's Speech. It was a glamorous evening, and a glamorous film, the kind of night—and the kind of film—that Weinstein once hosted regularly, that is, until his last few years in the wilderness, when he lost millions of dollars and, by his own admission, his love for making movies. Standing in front of the Murdochs and Kravises was the Harvey Weinstein people remember, the Harvey Weinstein whom, despite his infamous temper and penchant for infighting, people missed, the downtown impresario, the indie king, the man who with his brother, Bob, produced some of the best movies of the last 20 years, from Pulp Fiction to Shakespeare in Love to The English Patient. Here was the Harvey many had felt was gone forever.

This, at least, is the public Harvey Weinstein. The other Harvey, the one who has returned to actually making films, is on display a few nights later, sitting in a crowd of nobodies at the Clearview Chelsea theater, on West 23rd Street. The occasion is the first test screening of Submarine, a British coming-of-age movie he took on last September after successful showings at the Toronto Film Festival. The New York audience's reception is a disappointment, subdued at best, sullen at worst, and when Harvey stalks out into the lobby, he barely makes eye contact with the film's director, a young Londoner named Richard Ayoade.

"It's amazing, the humor just doesn't translate," Weinstein fumes to a circle of aides. "In Toronto they were on helium they were laughing so hard. These people, they don't get it. They don't get it. I just don't get it. It's like they need permission to laugh." Weinstein riffs through changes he can make to the film, which will be released sometime this year. Maybe a "place card" to establish the Welsh setting. Maybe toning down some of the heavy British accents. "We'll take down some of the dialogue, like we did in My Left Foot. Anyway, there's a problem with the film. This is the process. I'll fix it."

A moment later he shoots me a look, and a smirk, that pretty much says it all: after all the bad movies and bad decisions and bad, well, everything of the last five years, Harvey Weinstein is finally back.

Love him or hate him, and there are plenty in both camps, Weinstein is first and foremost a creature of New York, a personification of the best and worst traits: smart, arrogant, foulmouthed, temperamental, undeniably creative. At the point where Manhattan fashion and film and media and politics intersect, he is simply "Harvey," a single-name icon after all these years. Most nights he can still be seen gliding through downtown streets in his gleaming, chauffeur-driven black Escalade, same black suit as in his heyday, same rumpled white shirt, same sumptuous belly straining at the lowest buttons. But he's not the same Harvey, not really, not after all that's happened. His long climb back, into what appears to be a promising third act, has made him a bit humbler, a bit chastened.

Everyone in the entertainment world knows his story. A middle-class kid from Queens, a onetime concert promoter who emerged with his brother in the early 1990s as the leading maker and marketer of independent films, Weinstein made his name during an unprecedented streak, from 1992 to 2003, when his beloved Miramax studio produced at least one best-picture nominee every year. The contradiction that made him so fascinating was how a man who produced such wonderful films—Trainspotting, Cold Mountain, Good Will Hunting, to name a few—could produce such boorish behavior. In Hollywood, everyone seems to have a favorite Harvey tirade. The time he told The New York Observer he was "the fucking sheriff of this fucking lawless piece-ofshit town." The time he screamed at Terry McAuliffe, then chairman of the Democratic Party, over some now forgotten bit of political trivia: "You motherfucker! I'll rip your balls off!" (Weinstein denies this happened.)

That was Harvey Weinstein then and, though such outbursts seem rare these days, probably still is. An aide tells the story of a "slight" tantrum he recently threw on the set of a movie filming outside London, after which he apologized for "being an asshole," at which point someone piped up, "Yeah, but you're our asshole, and we're glad you're back." Ask his peers about Weinstein these days and you hear that kind of thing a lot. Where once he was viewed as a spitting, cursing blowhard, today, at 58, Weinstein is often described in warmer terms, as a throwback to the passionate, sometimes vulgar studio heads of yore, such as Harry Cohn and Jack Warner. Having sold Miramax to the Disney Company in 1993, then leaving in a rancorous dispute with its C.E.O., Michael Eisner, in 2005, he was surprised to find much of Hollywood actually cheering him on when he tried to buy back Miramax last year.

"I think just about everybody was rooting for them," says Tom Freston, the former Viacom C.E.O., "because, while Harvey is sort of the anti-Hollywood, underneath all the bluster people really do root for him because he is sort of emblematic of the Hollywood of yesteryear, the big, burly guy who steps on a lot of toes, who does it his own way. It harks back to the reasons many of us got into this business."

"There are still detractors, there are still people who remember the hell," says Bryan Lourd, the Creative Artists Agency talent agent. "But, look, everyone needs a healthy distributor for high-end art films because there are, like, two and a half of them right now. These things, these rarefied bets on the art business, have to work or we're all going to be living in a world of superhero movies or three-minute video clips from our retarded cousin in Baton Rouge. The world needs Harvey."

"I think I took my eye off THE BALL," ADMITSHarvey "I was out of it."

Harvey and Bob Make a New Media Company

If there is a lesson to be drawn from Weinstein's lost years, it is that hoary old bromide: Be careful what you wish for. Seven years ago, all Harvey and Bob wanted was their freedom—freedom from Disney's smothering supervision, freedom to make the films they wanted, freedom to branch out into the thrilling new world of multi-media. After a solid year of tortured negotiations, every twist and turn of which was chronicled in the Hollywood press, they finally burst free in mid-2005, leaving behind Miramax to start a new firm, the Weinstein Company, a vehicle that would not only let them make their own movies but give Harvey free rein to pursue his multi-media dreams. They would plunge into the Internet and fashion and publishing and television.

With Wall Streeters and hedge-funders tossing around billion-dollar investments like confetti, everyone wanted to be in business with the Weinsteins. And rightly so. During the time they ran Miramax, they had produced hands down the highest-quality movies of the era, for which they were showered with 249 Academy Award nominations and 86 wins, including 3 Oscars for best picture. They had all but created the world of modern independent cinema, and if Harvey's temper and the brothers' incessant squabbling made them unpopular in some circles, they had nevertheless emerged as genuine legends, the last great flamboyant impresarios of a Hollywood slowly being taken over by suburban accountants.

No sooner had they founded the Weinstein Company in a sleek suite of offices above Manhattan's Tribeca Grill than the money came flooding in—more than $1 billion in all, raised for them by Goldman Sachs. Nearly $500 million came from the sale of stock to a slew of gold-plated investors, including Dirk Ziff, Mark Cuban, Vivi Nevo, and Todd Wagner; another $500 million was available in a credit line for the brothers to use however they saw fit. Opening their doors for business in October 2005, Harvey and Bob announced an ambitious slate of more than a dozen new movies to be released in the next year.

There was just one small problem, of which almost no one, least of all their investors, had the first clue:

Harvey didn't want to make movies anymore.

By his own admission today, he was burned out. He had just gone through a difficult divorce from his wife of 17 years, Eve; he married his secwife, the British fashion designer Georgina Chapman, in 2007. But it was the Disney divorce that left the real scars.

"Fahrenheit 9/11—that started it," Harvey says with a sigh, shifting uneasily in a tiny chair as we finish breakfast outside his office. Release plans for Michael Moore's flamethrowing anti-Bush-administration documentary had triggered a long, drawnout fight between the brothers and Michael Eisner, all through 2003 and 2004. Eisner, worried about political fallout, refused to allow Disney to release the film. Ultimately the Weinsteins forked over $6 million of their own money to buy it back, then released it themselves. The movie earned more than $200 million, making it the highest-grossing documentary of all time, but the struggle took a toll on Harvey. "The whole thing," he says with obvious pain, "it was just disastrous."

Then there was Disney's refusal to allow him to make The Lord of the Rings—too expensive—and its refusal to back a Miramax cable channel. By the time Harvey finally gained his freedom, he wanted to do just about anything except make a him. "I really lost interest in making movies," he says. "I just didn't want to do it anymore. I was interested in everything other than movies, frankly." His ambivalence showed. None of those first Weinstein Company films—The Matador, The Libertine, TransAmerica— earned much money, or notice.

"DreamWorks waited 18 months to start producing, but Harvey didn't want to wait," recalls a former Miramax executive. "He felt if he sat out he would lose his edge. Well, the first movie was Derailed, with Jennifer Aniston and Clive Owen, which was pretty bad. Us Jews are superstitious. This was just bad Karma. How do you make your first movie and call it Derailed? It was a bad start."

As the new company began to grow in 2006, eventually hiring more than 200 employees in New York, London, even Hong Kong, Harvey and Bob charted a path that was sharply different from the old one at Miramax. By and large, due mainly to Harvey's burnout, they retreated from actively producing as many movies in favor of having subordinates snap up small, independent films made by others, eventually buying and releasing more than 70 titles between 2006 and 2009. There was a minor hit or two—Harvey's The Reader, with Kate Winslet, and Bob's Scary Movie—but most offerings tanked. More than a quarter failed to earn even $1 million at the box office. Thirteen brought in $100,000 or less.

"I haven t cleared this with Harvey, but Dm going to SAY THIS: I WAS NOT IN FAVOR of them [buying] Miramax," says Cablevisions Jim Dolan.

"I think I took my eye off the ball," Weinstein says. "From about 2005, 2006, 2007,1 was out of it. I thought I could oversee movies and have it done for me, so to speak."

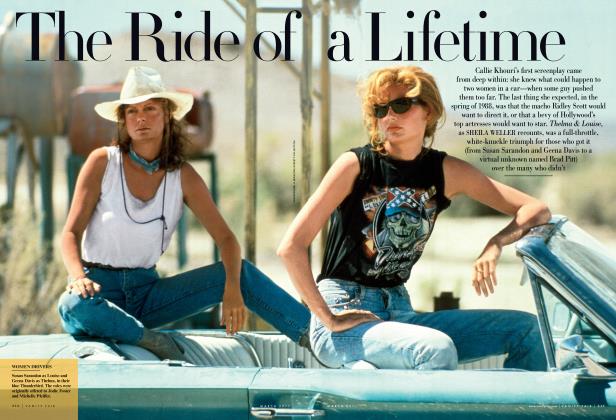

What interested Harvey, and took up much of his attention during these years, was a slew of non-Hollywood acquisitions. At Miramax he had already dived into publishing and television production, creating at least one breakaway hit, Bravo's Project Runway. But now, freed from Disncy's control and with $ 1 billion in play money, Harvey was able to indulge his every whim. His first acquisition, unveiled in May 2006, was a controlling stake in a two-year-old Web site called A Small World, which was intended to be a kind of Facebook for the rich. Harvey threw himself into its development, but today acknowledges that he hadn't a clue what he was doing.

"The trouble was I tried to make money" with the Web site, Weinstein says. "That was absolutely the wrong decision. You have to be able to lose money in these things for a long time in order to make a better product. But I was just fascinated by this stuff. I thought it would be fun and have fabulous payoffs. I thought it would take me in a whole new direction. But I was terrible at it. Terrible."

Next up, in October 2006, a stake in Ovation, a cable network devoted to the arts. Four years later, while still alive, Ovation _I_ i remains a very small operation. Then, in 2007, Harvey unveiled his most aggressive move to date, buying Halston, the fashion house. To outsiders, the motley collection of deals made little sense. But to longtime Weinstein-watchers, there were familiar pathologies at work.

"Harvey believed that Disney held them back from being a broader multi-media juggernaut," a former Miramax executive says, "so in his mind he wasn't content with having just the film side, so he went ahead with releasing all these movies, which he shouldn't have, but he went for the multi-media side, too. The problem was he was like a hungry kid who goes shopping. It was his insatiability. He was a kid with a chip on his shoulder. He needed to prove he could do it, and it turned out he couldn't. It was ridiculous. Halston, Ovation. None of it worked together. None of it had focus."

"Once they split from Disney, there was this sense of liberation, and of euphoria," says James Dolan, the chairman of Cablevision and a longtime Weinstein friend. "You have to put it in the context of the economic times. As a country we were pretty flush. Harvey's new company was a beneficiary of that. [Then] he got caught in the same economic downturn everyone got caught in. He went from euphoria to—how do I put it? He got close to getting scared."

"He had a classic case of hopeful expansion, trying to be a one-man conglomerate, which took him away from his real roots and talents, which is a hard-nosed maker of independent films," says Tom Freston. "I think maybe he thought he could pretend to be playing with the big boys, from Halston to television to doing a lot of things that were maybe out of his bailiwick. It appears now that just in the nick of time he's sort of recovering and entering what had been his real specialty, with some Academy Awardlevel pictures."

"He had been doing the same thing for 20 years," says Vivi Nevo, a media investor and Weinstein backer, "and you know, people lose their sight. They want to get involved in technology and fashion and everything else, which is not your focus, so you take your eye off the ball, trying to find synergy. You are not doing what you are 100 percent good at. It creates some headaches. He tried to go in new directions, and now he is back to reality."

From 2005 to 2008, any number of friends tried to guide Harvey back toward filmmaking. But he had stopped reading scripts. He had stopped going to the film festivals. "When I first got there, in 2008, the focus was not on movies," says Weinstein's baby-faced young president, David Glasser. "Harvey was focused on Internet and fashion and the global media picture. I had expected I would see this unbelievable guy cutting trailers till three in the morning, but he wasn't. He was just in board meeting after board meeting—Six Flags, Halston, all these things. It was a very different company than I expected.

And for Harvey, taking his finger off the pulse was not a good thing. I remember a moment where we kind of sat down, and he started saying, 'Look, I know what I need to do.' It was just getting back in touch."

@vf.com LET THE LITTLE GOLD MEN BLOG BE YOUR GUIDE TO OSCAR SEASON.

The turning point came during the summer of 2008, as the severity of the recession was sinking in. Business was down. The films weren't selling. Worse, the backbone of the Weinstein Company's cash flow, DVD sales, was collapsing as film-watchers increasingly turned to Netflix and pay-perview. "The home-video market crashed," Harvey recalls, "and 40 percent of our business got crushed." It was then, as the brothers began assessing their financial health, that they realized how much trouble they were in: they were drowning in debt.

By the summer of 2008 the Weinsteins had gobbled up almost $450 million of their $500 million credit line. The resulting interest payments, $40 million a year, actually surpassed their total overhead. Today, Harvey shakes his head at the memory. "Bob and I had never done debt," he says. "The investment bankers would say to us, 'Debt is cheap money.' No, it's not. Debt can be the most addictive thing in the universe, and it can kill you. You get used to living high off the hog. It was intoxicating. And so in 2008,1 just woke up and said, 'This is crazy.' "

"When we got the debt, remember, it was during the boom," says Glasser. "Debt became like a drug, as Harvey says. You get high on it—you can do all these things: I can do more and more. Well, we weren't making our numbers anymore. It wasn't running the way we wanted. Harvey knew the only way to survive going forward was to get rid of this debt."

There was already grumbling among the investors; the company had fallen behind on a $75 million loan from investor Dirk Ziff, who had resigned from the board. The New York press, especially the New York Post, got wind of the company's troubles and began a kind of slow-motion deathwatch, with articles regularly predicting the brothers' imminent demise. Somehow, Harvey saw, they had to rid themselves of the debt. But how? He had read Andrew Ross Sorkin's 2009 best-seller, Too Big to Fail, about the financial panic, and had been impressed by the portrait of H. Rodgin "Rog" Cohen, senior chairman of the white-shoe law firm Sullivan & Cromwell. He asked around, liked what he heard, then gave Cohen a call. It turned out Cohen was a huge fan of Miramax films, and he quickly got to work on a plan to remake the Weinstein Company's balance sheet. "Rog is King Solomon-like," Harvey says. "He got everyone together. He did it all."

Negotiations with Goldman Sachs and the various Weinstein investors would drag on for months, but in the end Cohen forged a surprisingly simple deal that made everyone happy and erased the debt. Goldman Sachs took delivery of more than 200 Weinstein-controlled films and will keep them until their rental income pays off the debt. Once it does, the films will be returned to the Weinsteins. To cope with that lost revenue, they cut their workforce in half, from a high of 225 employees to 109. The restructuring went so smoothly, David Glasser says, that they have now begun rehiring.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 342

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 295

As they fixed the company, Harvey realized it was time to get back to filmmaking. He really had no choice. The company not only needed hit films, it needed to regain its reputation as a purveyor of hit films. Beginning in late 2008, Harvey threw himself once again into the nitty-gritty of producing and buying movies. From this process sprang not only The King's Speech, which won a Golden Globe for Cohn Firth as best actor, but also several others now being mentioned as Oscar contenders, including Blue Valentine, The Company Men, and The Fighter. "I learned what I really love is making films, not the film business," Harvey says today. "I want to be on the set, meeting with writers, I want that freedom. I love it now."

All of this—the debt talks, the return to filmmaking, the recurrent predictions of the company's death—was still aborning last winter when, to Harvey and Bob's surprise, a rumor flew through Hollywood: Disney was putting Weinstein's baby, Miramax, up for sale.

The Disney Store

David Glasser heard the rumor first, in November 2009. "I went into Harvey's office and said, 'Miramax is going up for sale, for $1.2 billion. Do we have any interest?' " he says. "I knew it would be a touchy subject. I didn't know how he was going to react. And he was, well, subdued. He took a meeting with some potential partners, but he wasn't the Harvey where, you know, 'We're gonna get this and tear down a wall to do it.' The company meant everything to them. Harvey had closed that door, sealed it shut, and I don't think he was ready to try and get it back until it looked like we could."

Weinstein was torn. It is impossible to overstate what Miramax means to the two brothers, even now. It wasn't just that they had created it and run it all those years. It was that the company was named after their parents, Miriam and the late Max Weinstein; Harvey knew how much it meant to their elderly mother to get it back. Neither Harvey nor his people can publicly discuss the ensuing negotiations, which are subject to a confidentiality agreement. But Harvey will say that his first concern was whether Disney would even entertain his interest. "They won't sell to me," he told Glasser, "because they hate me. If it worked out, and I made the company a success when they couldn't, it would make them look bad."

Weinstein sent in CAA's Bryan Lourd to assess the situation. "So I dragged myself to [Disney C.E.O.] Bob Iger's house, and Bob was fantastic," Lourd says. "He actually wanted Harvey to get it. For all these reasons. It belonged to them, and it still belongs to them. Bob wanted to make that happen." A face-to-face meeting with Iger, Weinstein, and their advisers persuaded Weinstein of Iger's sincerity. By last January, Harvey had convinced his brother they should try to reclaim the company they both considered a birthright. "Bob was understandably concerned about eating the whole thing," Harvey says. "We were just getting healthy again, and to basically double our workload at that point, he thought it was too much."

Even at $700 million, the reduced price it turned out Disney was seeking, the Weinsteins no longer had a fraction of the cash they would need to buy Miramax. From the beginning, it was clear to all involved they would need deep-pocketed partners who would buy the company for them to run; the brothers would make their money via management fees. Last winter Harvey met with a series of potential partners, including Henry Kravis's KKR. He finally cut a deal with Ron Burkle, the Southern California investor. As an aide remembers it, "Burkle looked Harvey in the eye and said, 'If you want this, I want this.' " Fortress, a big hedge fund, signed up to furnish the rest of the purchase price.

"That's when we started to get excited," a Weinstein aide recalls. "I remember Harvey told his mother, and she was just thrilled. Thrilled. She goes, 'Harvey, who should I call? Should I call Bob Iger? If you want to close this, Harvey, I can do it for you.' By the way, if you know Miriam at all, she was serious. Totally serious."

All through February and March, the auction took shape. Disney, to the surprise of many, elected to have its own executives—a team led by Kevin Mayer—handle the process rather than hire a major investment bank such as Goldman Sachs. Only later would this prove a sore point. "If Disney had hired pros to do this, things would have turned out very differently," says one participant. Would-be bidders began slowly examining Miramax's books. KKR, Studio Canal, Lionsgate, and others studied the numbers and decided to pass.

As they did, Weinstein took weeks figuring out how he would incorporate Miramax into the Weinstein Company. The Miramax film library, its principal asset, consisted of 670 movies; together with the 350 or so Weinstein controlled, this would give Harvey more than a thousand films that, with the DVD market fast disappearing, he imagined a partner could help him stream directly over the Internet. He talked to Ted Sarandos at Netflix, Eric Schmidt at Google, and Jeff Bezos at Amazon and found each interested in a partnership, at least in theory.

But the key, as far as Harvey was concerned, was his longtime friend Terry Semel. Now an independent investor, after resigning as C.E.O. of Yahoo, Semel was open to Weinstein's entreaties. Harvey proposed that Semel come aboard to run a combined Miramax-Weinstein, which would at long last free the brothers from day-to-day management responsibilities and allow them to concentrate on filmmaking. In the end, Semel begged off, apparently to explore a possible purchase of the MGM studio.

Harvey forged ahead anyway. After several delays, initial bids were due on April 5. Disney set a floor of $600 million. Most Hollywood analysts valued the studio at between only $480 and $500 million, but Harvey felt his and Bob's intimate knowledge of the library was worth at least another $100 million. Burkle decided to bid the minimum, $600 million. Harvey personally delivered the bid to Disney headquarters, arriving 10 minutes before the five P.M. deadline. Disney's Kevin Mayer told him there had been only one other, by Pangea Media, a partnership between a Los Angeles construction magnate named Ronald N. Tutor and a troubled Hollywood stalwart named David Bergstein, who was the subject of myriad lawsuits with creditors trying to force five of his companies into involuntary bankruptcy. Harvey knew all about Tutor and Bergstein. He climbed back into his limousine, confident, feeling there was little chance Disney would sell to a pair of Hollywood nobodies over the Weinstein brothers.

Around nine a Disney executive telephoned to say a third bidder, a family trio of Israeli-born financiers known as the Gores brothers, had lobbed in a late bid and was being allowed into the auction. Harvey protested that this was against the rules, but it was no use. "That," a Weinstein adviser says, "was our first sign that maybe not everything here was kosher."

Inside the Weinstein-Burkle-Fortress bidding group, the mood the next day was buoyant. Their initial offer was low, it was true, but no one feared Pangea, whose bid was valued around $750 million, much less the Gores brothers, in large part because neither competing bid appeared to be backed by firm financing commitments, as theirs was. Burkle decided to use this as a battering ram and, in a weekend meeting at Iger's Brentwood home, he and Harvey argued that they were the only legitimate bidders and thus should be given an exclusive negotiating window. Iger agreed, and later that week Disney said it would deal only with Burkle and Weinstein for 60 days, during which the other bidders would be idled. The Gores brothers eventually bowed out.

Teams of analysts and investment bankers plunged into the minutiae of Miramax's financial statements, studying how much the company was worth. After almost a month of work, Burkle and Harvey agreed they could boost their bid as high as $625 million. Bob Weinstein, however, remained unconvinced. "Bob thought the price was too high, and frankly feared the workload," says a Weinstein aide. "Harvey told him, 'We're not going to have to go knock on doors selling DVDs we're going to stream everything over the Net. They'll sell themselves.' " Yet Bryan Lourd too was wary. "The deal Harvey was going to accept, and that Bob was reluctant to accept, I was telling him not to do it," he says. "But Harvey's love for that name was driving it."

After Bob Weinstein reluctantly agreed to move forward, talks with Disney intensified. Finally, in mid-May, after long days of negotiations that left everyone involved drained, the two sides tentatively agreed on a purchase price: $611 million, subject only to the Weinstein group's completion of its due diligence. Harvey was overjoyed. He called his mother and told her the company would be theirs. Then, believing nothing but details remained, he flew off to Cannes to host a fund-raiser, confident that Miramax was within his grasp.

In the final hours, however, a glitch developed. Burkle's people found it and brought it to Harvey's attention. Deep inside Miramax's financial statements, revenues from several films, including Robert De Niro's Everybody's Fine, were still being carried as estimates, rather than actual numbers. In every case, the actual revenue was lower than the original estimate. It was just the latest of dozens of similar problems they had found with Miramax's numbers.

"It was unbelievably sloppy recordkeeping, the kind of thing you just don't think a public company would do," says a Weinstein adviser with a sigh. "You've never seen an asset for sale the way this one was. It was awful. Finding things, it was like a scavenger hunt. It wasn't too worrisome, not at first. So we brought this to Disney's attention, and at that point I think they were frustrated that we kept finding assets with problems. We weren't the easy buyer that was going to write a check and be done. We said, 'Look, there needs to be a [price] adjustment. We need to bring the price down.' People were tired, frustrated on all sides. And Disney took an approach that was just shocking to all of us, which was 'Yeah, O.K., so what?,' and lashed back at us and said, 'You've got 24 hours.' It was just shocking."

It was May 21. Burkle told Harvey he was lowering the bid. The question was how much. Weinstein felt the adjusted financial statements justified maybe a $10 or $15 million drop in the offering price. Burkle, however, felt the number was closer to $50 million, suggesting the group submit a final bid of $565 million. Harvey argued strenuously against this. Privately, he felt that Burkle had grown overconfident, that with no remaining bidders other than the flimsy Tutor group he was using the newfound discrepancies as an excuse to lower the purchase price and save money. "He thinks he can get away with this!" Harvey fumed to an aide. As one of his advisers recalls, "We told Ron, 'You don't know the Disney Company. You can't do this. You don't give Disney a $50 million haircut.' Harvey was worried they would just say, 'Fuck you,' and walk away."

The Weinsteins argued for an offer of $595 million and no less, but Burkle would not be swayed. "Ron was not dishonorable— he was just being tough," a Weinstein adviser says. "He told us, 'They're not going to dismiss the offer. They can always come back to us.' " Still, Harvey was worried, more so when he learned that Burkle had submitted the offer in a letter, rather than via a face-toface meeting. "Ron and Bob [Iger] should have sat down," says the adviser. "But they didn't." Still, Harvey remained upbeat. After all they had been through, he couldn't believe Disney would shut them out. At one point, he telephoned his mother and said, "We're still going to get it."

Harvey's Third Act

Harvey was in Cannes the next day, where he was scheduled to host his annual fund-raiser to benefit AmFAR, a leading AiDS-research philanthropy. It was a gala affair, held at the Hotel du Cap, with President Clinton and scores of stars in attendance, including Sharon Stone, Ryan Gosling, Annie Lennox, Robert Pattinson, Eva Green, Josh Hartnett, and the cast of Inglourious Bcisterds. The evening's high point was Gosling's keyboard serenade, during which he lavished kisses on an actress portraying Harvey. During the auction, Pattinson sold two kisses to the winning bidders' daughters for around $26,000 each. A saxophone autographed by Clinton brought nearly $175,000.

At every break, Weinstein stepped into the wings to caucus with David Glasser, who had a cell phone glued to his ear, fielding updates from Los Angeles. When the news finally came, it was not good. "We have a problem," Glasser said. That morning in California, Disney had responded to Burkle's letter with one of its own, rejecting the $565 million offer and, to Weinstein's dismay, ending the talks altogether. "It was just a massive 'Fuck you,' " the adviser says. Harvey couldn't believe it. He telephoned Burkle, who was arriving in Cannes that night; he couldn't believe it, either. "They're not going to leave you at the altar," he assured Weinstein. "Not at this point."

But they were. In those first hours, and in the days to come, everyone on the BurkleWeinstein team pelted Disney executives with phone calls in a desperate attempt to reopen the bidding. But Disney would not be moved. As Harvey watched in horror, the company announced it was entering into an exclusive bidding period with Ron Tutor's group, which had put its house in order by marginalizing David Bergstein. Burkle and Weinstein felt sure it was only a matter of time before the Tutor bid fell apart. But it never did. Six weeks later the deal was done—for a reported $660 million. Ron Tutor, of all people, would now own Miramax.

Harvey was shattered. The toughest part was telling his mother. Miriam said she felt certain they would still get it. Harvey said they wouldn't, not now. It was over. Once again Miriam demanded to telephone Bob Iger. The lawyers, however, wouldn't even think about it. (Disney spokespeople didn't return repeated calls seeking comment. A Burkle spokesman declined to comment, but says he has "no problem" with this version of events.)

Behind the scenes, however, the Weinsteins refused to surrender. As Hollywood journalists moved on to other topics, they quietly regrouped on two fronts. The first was a negotiation with the Tutor group; Harvey felt he could forge a partnership to buy Miramax together. "We tried to have a meeting between Ron and Harvey, but Disney found out and threatened to kill the whole deal," says a Weinstein aide. "Disney knows we know where the bodies are buried, and they don't want us telling Tutor." Weeks later, however, Weinstein and Tutor did meet face-to-face. Weinstein left impressed. "Not such a bad guy," he mused. Eventually their talks led to the Weinstein Company's agreeing to "jointventure" several sequels of old Miramax movies such as Bad Santa, Shakespeare in Love, and Rounders.

At the same time, the Weinsteins brought in two of the country's top attorneys, Bert Fields and David Boies, to confront Disney. From the very beginning, Harvey had argued that the terms of the agreement they had made in 2005, when the Weinsteins left Disney, prevented certain Miramax movies from being assigned to third parties. He had joined the auction process, in effect, under protest. Once Fields and Boies got involved, they realized he had been right about his claim to the backlist films. After several months of negotiations, Disney quietly agreed to a settlement in which it will pay the Weinstein Company $32.5 million in cash, hand over its 50 percent stake in Project Runway, and reduce its share in four jointly owned films, including Scary Movie and Spy Kids, to 5 percent from 50 percent. The $75 million settlement helped Harvey recover from what, by his own admission, was a wrenching defeat.

A number of friends, however, thought it was all for the best. "I haven't cleared this with Harvey, but I'm going to say this anyway: I was not in favor of them doing Miramax, and I think he might be better off without it," says Jim Dolan. "I don't think he feels the same way. But this allows him to focus on the thing he does best."

"I'm actually happy it didn't work out," seconds Bryan Lourd. "It's a much better structure now. It's about keeping his eye on the ball and making good pictures.... I'd say their prospects are really good. No one should make the mistake of thinking that three or four movies are going to change their fate. And I don't think any of these pictures will. What will change their fate is a disciplined approach to a balanced schedule, with Bob movies and Harvey movies and new directions and new franchises. Those can be built, those will come, out of just doing the work, just the basics of reading scripts, meeting new talent. Harvey was too highfalutin for a while. They're really on track now."

Today, with the financial re-structuring A in place, Harvey Weinstein is back to what everyone wants him doing, making and marketing movies. At lunch at Manhattan's Tribeca Grill one frigid day in December, he is sorting through advertisements for The Company Men, a topical drama he is distributing about laid-off executives, starring Ben Affleck and Tommy Lee Jones. "Obama and Hillary Clinton both asked to see it, and I wouldn't give it to them," he says. "Hillary said to me, 'Of all the movies you've made, this one is the most important.' I want Obama to see this movie publicly. This needs a Washington screening with the president of the United States and the secretary of state."

He glances over his sweet-potato gnocchi at David Glasser and Victoria Parker, a V.P. at the company. "Yeah?" he asks. They nod.

Weinstein sighs. A movie that will ask audiences to sympathize with wealthy white men who suddenly find themselves out of work—it won't be easy. Weinstein shrugs; this is all in a day's work. "Tough movie," he says, nodding. "Tough movie. I'm hoping for a miracle."

It wouldn't be the first.

FROM THE ARCHIVE

For these related stories, visit VF.COM/ARCHIVE

The Weinsteins and Miramax's early days

(Peter Bis kind, February 2004)

How Max and Miriam Weinstein inspired their two sons(Bob Weinstein, April2.003)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now