Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

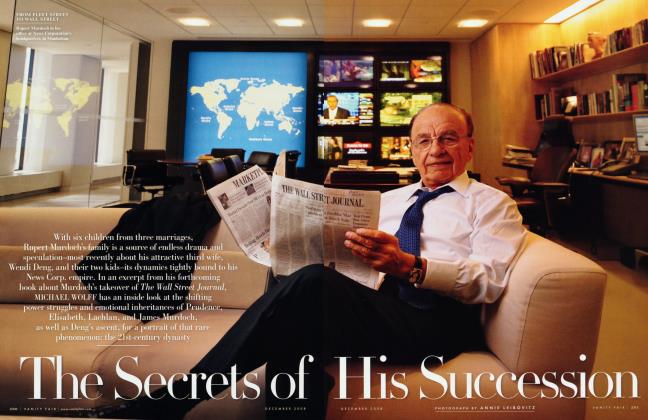

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAfter buying up London's most exclusive dining establishments, Richard Caring wants to create a luxury-restaurant empire-imagine Annabel's and Le Caprice in Dubai. To food snobs and snob snobs, it's a death knell, but what if it's just the future?

December 2008 Evgenia PeretzAfter buying up London's most exclusive dining establishments, Richard Caring wants to create a luxury-restaurant empire-imagine Annabel's and Le Caprice in Dubai. To food snobs and snob snobs, it's a death knell, but what if it's just the future?

December 2008 Evgenia PeretzPicture, for a minute, a perfectly coiffed London billionaire. He’s just nabbed his first aardvark-in-formaldehyde by Damien Hirst for £10 million. This is his moment—and so he’s at Scott’s in London’s Mayfair district, savoring a dozen spéciale de claire oysters with his beautiful wife. He notes his fellow diners: Tony and Cherie Blair, and over there, Keira Knightley. Not too shabby, he thinks. His suit is Savile Row. His watch is from Patek Philippe. His mollusks are from Richard Caring.

Around the comer on Berkeley Square, a white-haired lord and his wife are sequestered in a cozy banquette at Annabel’s stoically attempting to blot out that their son and heir is all over the tabloids, having been caught soliciting sex from an Amazonian blonde named Bruce, whilst wondering if that fellow over at the bar will ever shut up, for God’s sake. The gimlets they’re enjoying (their fifth pair of the evening, if anyone’s counting) are being provided by Richard Caring.

Across town at Electric House, in Notting Hill, a publicist, a modeling agent, and other assorted “media types” are shrieking incoherently and taking an unusually high number of joint trips to the loo. The chipolata sausages sitting on the table are courtesy of Richard Caring.

At this point, if you are a Londoner who bears any resemblance to one of these archetypes, all the food you’re eating and drinks you’re enjoying are being provided by Richard Caring. If you want to avoid it, you’re going to Au Bon Pain. Until 2005, Caring was known simply as the tanned fellow who supplied merchandise to his billionaire friend Sir Philip Green, who with his family owns British Home Stores and Arcadia Group, which includes Topshop, in London. In 2005 he turned to what Britain calls “the catering business” and in three years has acquired London’s very best restaurants for some very high prices. First he bought the Caprice group (including the Ivy, Le Caprice, J. Sheekey, Daphne’s, and Bam-Bou) for $57.2 million, followed by Scott’s, which he bought for $614,495 and refurbished for about $10.5 million. In June 2007, for $198.8 million, he snapped up the ultra-exclusive, members-only clubs of Mark Birley (which in addition to Annabel’s include Harry’s Bar, Mark’s Club, George, and the Bath & Racquets Club). In January 2008 he bought an 80 percent stake in Soho House, which also includes Shoreditch House, Electric House, Babington House, and High Road House, for another $205.4 million. To provide some context, that’s like one man in New York suddenly owning the Four Seasons restaurant, ‘21,’ Cafe des Artistes, Union Square Cafe, Nobu, Balthazar, and Pastis. Come to think of it, he may soon own Balthazar and Pastis if he gets his way—but more on that later. He’s on an acquisitions-andexpansion blitz, taking his brands to numerous U.S. cities (including Los Angeles, Miami, and Chicago) as well as Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Istanbul, and, especially, Dubai. The plan is to open in 22 countries over the next seven years. Soon, he will have the world’s first global luxuryfood conglomerate. But is such a thing really possible?

"YOU CAN’T KNOCK IT, THE NEW WAY OF DOING THINGS,” SAYS ONE ARISTOCRAT. "IT’S VERY COMFORTABLE.

For the food snobs, a restaurant is a proprietorship, and you just can’t treat it like a Starbucks outlet. “The notion of a conglomerative luxury restaurant is almost a contradiction,” says a key member of the London restaurant fraternity. “All the restaurants he’s bought up to now were built upon personal attention. They were built by restaurateurs, not restaurant owners.” Sam Hart, who with his brother Eddie revamped the Soho institution Quo Vadis, says, “It is not a good situation when one person controls so many restaurants. It’s difficult for creativity to flourish.” And the money he has spent? “Ludicrous,” says one restaurateur. “He must have a printing press somewhere to manufacture all his money,” says another.

The regular old snob snobs feel that his whole “corporatizing” thing is beyond tacky. “‘He’s trashed [Annabel’s] completely and we’re not going to have anywhere to go and this is awful!”’ says one social fixture, imitating the hysteria that ensued after Caring bought the crown jewel of the Birley group. It didn’t help that he came with some most distasteful baggage: a house in London nicknamed the “Versailles of Hampstead”; a shooting lodge on the border of Devon and Somerset that was known to be hopelessly nouveau, complete with a helipad and way too many pheasants tearing away at the neighbors’ plantings; and, worst of all, a close friend in Sir Philip Green, the notorious retail merchant who proudly awarded himself $2.1 billion—the largest bonus in British corporate history—paid to his wife in Monaco, where it would not be taxed.

But if a luxury-food conglomerate is feasible, Caring may be just the man to pull it off. He is not simply another successful businessman hitting middle age and buying trophies. He’s doing for food what he has done for clothes. At a time when high fashion was only for the very rich, Caring was bringing chic, or at least semi-chic, fashion to the masses, by manufacturing clothes in Asia and selling them in stores like Marks & Spencer. As a result, a great many more European women looked better. Now he’s doing the same thing for fine dining, boiling down successful brands into formulas that he believes can be replicated and applied in cities where Tony Roma’s now qualifies as cuisine. He’s not making the food any cheaper, but he is making it available. What Conrad Hilton did for luxury hotels in the 1950s and 60s, Caring proposes for Dover sole.

And he is far from the cigar-chomping beast the hysterical snobs of London might expect. A trim 59-year-old in Armani with a dazzling tan, very white teeth, and steel-gray hair swept back in a slight bouffant, Caring has a kind of cool 80s stylishness and quiet vanity. (He is rumored to have once decided against buying a site because he would have had to wear a hard hat to tour it.) He is studiously polite, asking permission, for example, to take off his jacket in his own office, which is sprawling and features two large Degas drawings of ballerinas. “He’s got the most beautiful manners,” says P.R. man David Wynne-Morgan, who was Birley’s right-hand man for 43 years. “It was the last thing I would have expected of him from what I had read.”

"UNFORTUNATELY, I LIKE MOST OF THEM MORE THAN MY OWN!” SAYS KEITH McNALLY OF CARING’S RESTAURANTS.

He doesn’t gush about balsamic reductions or rarefied vintages. What Caring thinks about—and talks about—are “positions” and “directions.”

“The idea of [buying] Balthazar [the fashionable Manhattan bistro owned by Keith McNally] would be another customer again, another profile, so it would give us width,” he explains, sitting across from me at a conference table.

Buying McNally’s empire appealed to him, he says, “because I’m very keen to get some depth in the States.”

“We bought the Robinsons-May [department store] site in L.A., for condominiums, so that’s our luxury position.”

His customers aren’t old friends or new obsessions or lovable eccentrics. Rather, they represent “60,000 quality names and addresses.”

If he seems to lack passionate beliefs about how to brine chicken or where to seat a suddenly disgraced media mogul, it’s because he does. Caring knows these details are important, but he’s the first to admit he’s no expert on them. That’s what management is for, he says. Caring has inherited some of the best, and he’s not messing with it.

But will the standards of London’s top restaurants continue when they all have the same guy at the top? Can a trophy remain a trophy if there are 19 of them all over the globe? Caring believes the answer is yes. “Let me show you something,” he says, getting up in the middle of our interview. He returns with a letter Mark Birley sent out to the Annabel’s membership at the time of the sale, assuring them that Caring would respect and maintain tradition. To win Birley’s trust was no small feat, as he was famously fussy and stingy with praise. Caring had the letter framed.

Others believe Caring can do it, too. His friend Sir David Tang, the Hong Kong entrepreneur who co-owns Cipriani Hong Kong and founded the international clothing chain Shanghai Tang, says, “I think that Richard Caring understands the delicacy of some of the rather conservative and perhaps pompous elements of the [Birley clubs’] membership and then the much more relaxed way and less pompous, less feudal feel of the modem age.” Indeed, despite the gossip of the toffs, Annabel’s is still the place to be, even if one opens in Dubai. “Anything that stands still moves backwards,” Caring says. And as to the question of overpaying, if his plan works, he will have made another fortune. “I think he paid too little,” Tang says. “As we are speaking, there are probably people trying to seduce him to sell at a premium.”

Growing up, Caring had no access to the kinds of eating experiences he’s now spreading throughout the globe. His father, Lou Caringi, was an American soldier injured during the Second World War who convalesced in London, under the care of Caring’s future mother, a British nurse named Sylvia Parnes. After dropping the i from his last name and putting down roots in North London, a largely working-class Jewish neighborhood, Lou set up a small showroom in the fashion district, north of Oxford Street. “It was needs must at the time,” says Caring. When he left school, at age 16, he briefly apprenticed in the real-estate business, but was soon called away by his father. “He said, ‘Come on—I need some help. The family has to get together and do this.’” Both Richard and his mother joined Lou, with Richard packing and shipping dresses. Two years later, London’s Carnaby Street era was beginning, and Caring got creative. Together with a girlfriend in fashion school, he designed a set of dresses that actually looked good. Caring had them made by the local Greek-immigrant “outdoor factories” and began pounding the pavement. “I had a target that I had to sell 200 [dresses] a week. They would cost a maximum of £2 [at the time, $5.60], and I would sell them for 69 shillings and 6 pence, which was about £3.50 [$9.80]. I was out there knocking on doors. I had a little route of shopkeepers that I would take an order from. Someone would buy five, another girl would buy eight. If I got an order of 36 it was a big day for me.”

Caring didn’t dream of fabulous wealth and luxury. “I was interested in being able to take out a girl to a decent restaurant and have a car that I wasn’t ashamed of,” he says. Soon, he was able to make his rather modest goals come true. Two hundred dresses a week turned into 500, turned into 1,000, turned into 60,000 to 70,000 a week. By 1971, he had landed a beautiful wife: Jacqueline, a model whom he had first spotted on the catwalk. Around the same time, a shrewd buyer made the suggestion: Why aren’t you in Hong Kong?

“I hadn’t even heard of Hong Kong,” Caring recalls. “My geography was awful.” With a why-not attitude, Caring and his father decided to send one of their employees to scope out the scene for a few days. He ended up staying for seven months. The materials, the labor, it was all chicken feed over there. This was gold. In 1980 he moved to Hong Kong with his wife and young son, Jamie (his second son, Ben, would be born there), to oversee his growing business. Other companies had discovered the promise of the Far East, but they were making “basic stuff,” Caring says. The Carings, on the other hand, were making fashion—well, fashion enough to appeal to discerning shoppers who might be on a budget. Before long, the company had a virtual monopoly on the low-cost fashion industry in the U.K., supplying clothes to chains such as Marks & Spencer, Next, and Philip Green’s Topshop.

When Green purchased the department store BHS in 2000, he and Caring became virtual partners, with Green reportedly cutting out all other suppliers and directing his buyers to go through Caring. With Green’s other company, the Arcadia Group, which Green bought for about $1.6 billion in 2002, their partnership flourished even more. In the first year, Green doubled profits and more than doubled Arcadia’s value.

Green was the flashy one—he threw his son an estimated $7.4 million Bar Mitzvah, complete with performances by Destiny’s Child and tenor Andrea Bocelli—while Caring was his little-buddy workhorse. That is, until Green’s 50th birthday (for which he flew 200 guests to Cyprus for a three-day extravaganza concluding with a toga party). Then Caring publicly presented him with a red Ferrari Spider, thereby making his point: he was no longer content to remain in the shadows.

In 2004, the opportunity to step out of the “rag trade” into something more glamorous fell into his lap when Caring got a call from a friend saying that there might be an opportunity to buy Wentworth Club—a historic 19th-century house in Surrey, around which was built the 1,750-acre Wentworth Estate and three of the most prestigious golf courses in Europe. It oozed “class,” and for Caring it also held personal appeal. Caring had played golf since childhood; he had had a golf scholarship at the Millfield prep school, and played competitively—once, even on a course at Wentworth. (A large watercolor of the grounds hangs in his office.) His attack was aggressive. He paid $232.9 million for Wentworth when the book value was only $197.1 million. The golf snobs were beside themselves. “I was asked questions like ‘Are you going to turn this famous golf course into a racetrack? ’ ” recalls Caring. “ ‘Into a casino? Into residential housing?’ I said, ‘No. All I want to do with Wentworth is maintain the image and the character and just move it forward.’”

“I WAS ASKED QUESTIONS LIKE ARE YOU GOING TO TURN THIS FAMOUS GOLF COURSE INTO A RACETRACK?’”

Among the steps he took to move it forward was to bring in modern cuisine. He sought out the Caprice group, then owned by Luke Johnson (the son of the historian Paul Johnson and current chairman of the U.K.’s Channel 4), to provide the club’s food. In the midst of those negotiations, another seed was planted in his head. “I think I made a statement like At the price you’ve just quoted me, I might as well buy the company,”’ recalls Caring. “The inference I got from that was: Maybe there was a possibility to acquire it.”

The Ivy and Le Caprice—the two jewels of the London restaurant scene—were owned by Luke Johnson’s restaurant group. Both theater haunts, before disappearing under the radar, they had been bought in 1981 (Le Caprice) and 1990 (the Ivy) by Jeremy King and Chris Corbin (current owners of the Wolseley, on Piccadilly—and partners with the editor of this magazine in a small restaurant venture in New York), who gave them fresh buzz and mystique. The Ivy, especially, came to be bursting with important names from the worlds of theater, movies, politics, literature, art, and journalism. It was a club, really, and the management wanted to keep it that way, giving away three tables maximum a day to people who were unknown. According to food critic and Vanity Fair contributing editor A. A. Gill, who wrote a book about the Ivy, the daily morning meeting between Mitch Everard, the manager, and waiters would go something like this: “Table Four is Mrs. Hirschvitz. She’s having dinner with her client. Move her to Table Five, because the table next to her is another agent and they don’t want to be sitting next to each other. Dustin here. Salman Rushdie is going to be in the corner there—I think he’s with a new girl. Be particularly nice to her. The Pintos will be over in the far corner. Remember that she’s not eating onions at the moment.”

“There was no form to fill in,” says Luke Johnson, who bought the Ivy from King and Corbin in 1998 for $24.2 million, “but you knew if you were in and you knew if you were out.”

Caring paid $57.2 million for the Caprice group, of which Johnson was majority owner, and threw in another $104 million three months later for Johnson’s 23-outlet pizza chain, Strada. According to a source with knowledge of the deal, Caring had done the minimal due diligence and was practically flying blind. “Everyone thought I’d gone nuts,” says Caring. “‘How can you pay £57 million for a pizza restaurant?’” Less than two years later, he would sell off those pizza joints for $286.9 million, making a tidy profit. And now he owned the Ivy, the kind of restaurant he’d once been barely allowed to set foot in. The day after the deal was complete, he called the restaurant: ‘“I’d like to book a table for dinner tonight,’ I said, and they said, ‘I’m sorry?’ I said, ‘I’d like to book a table for dinner tonight for four people.’ And they said, ‘Who’s calling?’ And I said, ‘Richard Caring.’ ‘What time would you like to come?’ I’d waited 25 years to do that!”

With the Ivy and Le Caprice under his belt, it was time for his social debut. He found himself a cause—the Children’s Charity, which fights child abuse and pedophilia—and threw a $13.7 million benefit for 480 people, including Elizabeth Hurley, Sting, Jimmy Choo founder Tamara Mellon, and many of the most prominent figures of London society. No one had heard of this Richard Caring, but the invitation piqued everyone’s curiosity: a giant Russian matryoshka doll, inside of which was a bottle of vodka and an invitation to fly by private jet to St. Petersburg. It asked for measurements, which meant only one thing: a fancy-dress party!—something rich Brits can’t resist. En route to Russia, the guests sipped champagne while being entertained by comedians wearing Russian peasant outfits. When they arrived in their hotel rooms, tailor-made 18th-century Russian costumes were waiting, while seamstresses buzzed about making last-minute adjustments. The next 48 hours were a caviar-and-champagne orgy, complete with performances by the Kirov Ballet, Sir Elton John, and Tina Turner; a charity auction held by Sotheby’s Europe chairman Henry Wyndham; and a surprise visit from Bill Clinton, who dressed up like a Russian general.

The guests didn’t know what to make of it all. The party “was seen very much as a man trying to launch himself into society,” says one of the guests. But Caring’s actual behavior was not that of a showman. Rather, he seemed like a polite man from, well, the rag trade. “He was the person with the tape measure around his neck,” says Vassi Chamberlain, an editor at Tatler and one of the guests. The party earned the charity $24.9 million and was deemed the most extraordinary weekend anyone had had in a long time.

"THE IVY IS A LONDON-THEATER INSTITUTION WHAT THE HELL IS IT GOING TO DO... IN THE MIDDLE OF DUBAI?”

The big gesture—this was Caring’s way of doing everything, including, for example, shooting, a sport he took up only three years ago. A young aristocrat who had the opportunity to shoot at Caring’s country estate explains that a traditional English shoot consists of “old tweeds, a sausage roll, and a glass of sloe gin at 11 o’clock. And you’re not supposed to make a big fuss about how many birds you shoot.” But Caring’s lodge, in addition to the helipad, has a modern design and “a butler with a tablecloth and this whole bar laid out, incredible herbs and sandwiches.” A little gauche, maybe. “But you know what?” says this source. “You can’t knock it, the new way of doing things. It’s very comfortable.” If there is a person keeping Caring’s ego in check, it’s his wife, says his friend Christopher Biggins, an actor. “She won’t have any nonsense,” Biggins says. “When you go on the boat with them”—a 200-foot yacht—“it’s not all the grand people you might think. It’s really old friends who’ve been friends for 20 or 30 years. The grounding comes from her.”

But with the next chapter in Caring’s rise—the purchasing of the Birley group—London’s establishment felt he’d gone too far. A national treasure in London’s high society, Annabel’s was said to be the only nightclub ever visited by the Queen. Birley represented the ultimate in British snobbery and good taste, fanatical about every last detail, from the way the butter was rolled to how the napkins were starched. Imagine Caring—Philip Green’s close friend— thinking he could just step into Birley’s shoes by waving around obscene amounts of cash! According to one story making the rounds in the restaurant world, a Brit, asked by an American whether Caring was going to ruin Mark Birley’s clubs, responded, “There’s no reason why he should ruin them.” Then he hesitated: “Just so long as he doesn’t let his friends in.” Was this really just a sign of a deep-seated anti-Semitism? “The British establishment, the aristocracy, the people who are members of Annabel’s and who have been since day one,” says a social observer who has come to know Caring well, “they will never explicitly say this—but [they didn’t like him] because he’s Jewish.” In fact, in the first weeks of Caring’s taking it over, members could be heard muttering to one another, “I can’t do Annabel’s any longer. It’s just sort of loud, fat Jews.” While the British press didn’t dare wade into the anti-Semitism issue, it did print complaints that he had trashed Annabel’s.

Caring was devastated by the reports, says a club member in whom Caring confided. He had worked hard to earn Birley’s confidence. Now he simply put his head down and worked quietly to win the confidence of the members. When, for example, one member wrote him saying that he could no longer have anything to do with the club, Caring wrote back, “Give me a chance.”

He also sought out the advice of David Tang, a close friend of Birley’s who had managed to be both a member of the new rich and beloved by society. Tang, expecting an egomaniac, was impressed: “When you meet somebody [who has] actually bought something trophy, you cannot but expect that person to be slightly pleased with himself. There was nothing like that in Richard, and he was genuinely interested to hear what I had to say.” Tang didn’t feel it was his place to give concrete advice about the direction to take Annabel’s, but he did share his basic belief.

“There’s a balance between what you want to do with your members and what you want to do yourself,” says Tang, “and I’ve always held this idea that clubs are inclusive rather than exclusive.” All that grousing about the right sort and the wrong sort struck Tang as nothing more than jealousy. “If I were Richard Caring, I wouldn’t give a toss, and I’ve told him so.”

Alas, it’s still a subject Caring is sensitive about. When I ask about the difficulty he has experienced in confronting London’s snobbish elements, he responds, with an affable but somewhat nervous laugh, “Do you want to get me shot?” At pains not to offend the establishment, he says carefully, “British people are more protectionist. It’s tighter here. You have to prove yourself here. Once they do accept you, they are very solid, very loyal.”

Birley’s clubs have changed since Caring took over. “[Mark’s clubs] were commercially successful by being overtly, totally noncommercial,” Wynne-Morgan explains. “For Mark, the clubs were not just his business, they were his whole life and very justification of his existence.” Now they are part of a real conglomerate with an eye on the bottom line, as are the other clubs. Membership at Annabel’s has broadened. Circulars are now sent out to members advertising special events such as musical performances at Annabel’s and wine-tasting nights at Harry’s Bar. A few corners have been cut. The truffle guy at Harry’s Bar, says one source, used to go to Tuscany to find the white truffles. He’d take a couple of weeks and visit his family there. Now the truffles are purchased from a supplier. A longtime Annabel’s staff member says that Caring’s C.E.O., Des McDonald, wants the clubs to be filled to 100 percent capacity each night, just as Scott’s is, even if that means rushing long-term members out the door. Dress-code standards have fallen through the cracks, too. “Caring may ask why there’s a guy at the bar wearing a T-shirt,” says this source. “Someone will point out, ‘But it’s Marc Jacobs.’ He’ll say, ‘Oh, O.K.’ Mark Birley never would have stood for that.”

It all was too much for Alberico Penati, beloved chef at Harry’s Bar for 20 years, who left a couple of months after the sale. “It’s not my cup of tea to work for a big company, because I am an artisan,” says Penati, now the chef at the gaming club Aspinalls. “An artisan is a small thing. There is no one director, then another director, then another director. There is just me and the owner. Simply said.”

Then again, other staff members find Caring’s more democratic approach refreshing. “He listens to our advice and he gives us quite—how can you say?—a free decision on certain things,” says Luciano Porcu, the utterly charming manager of Harry’s Bar. “Like, for example, one day I was talking to him and he told me, ‘So, how’s it going?’ I said, ‘Well, I had someone complaining that we still have jacket and tie, no jeans, no sneakers.’ And he says, ‘What would you do?’ I said, ‘I would keep it the way it is.’ ‘And so let it be,’ he told me.” And at the end of the day, it’s hard to imagine that a truffle not personally plucked from the Tuscan countryside will spoil anyone but the biggest food snob’s evening. It’s hard to conceive that a performance at Annabel’s by Bryan Ferry doing all the old Roxy Music hits should be so offensive—simply because it didn’t happen in Mark Birley’s day. Wynne-Morgan sums it up: “I think he’s trying extremely hard to maintain the standards of Annabel’s. Equally, you know, things shouldn’t stand absolutely still. We are now in a different era with different values.”

The Ivy, too, has been knocked around a bit. “It’s football wives from New Jersey,” says one high-profile source. “The media figures and crucial showbiz types that gave it such a buzz are only there in limited quantities.” Many find the thought of the Ivy opening up in Dubai puzzling. “The Ivy is a London-theater institution, steeped in history,” says a source once dedicated to the place. “What the hell is it going to do in some sort of marble building in the middle of Dubai?” And some aren’t so crazy about the Club at the Ivy, which Caring has just opened upstairs and which features a sushi bar, a screening room, and a drawing room.

"RICHARD’S GOT THE MOST BEAUTIFUL MANNERS. IT WAS THE LAST THING I... EXPECTED."

“Where the problem comes in is when Richard Caring suddenly goes out and splurges on a whole load of boat and car memorabilia, to litter around just to make it look ‘authentic,’ ” says a prominent London restaurateur. “As they say, ‘Mark Birley he ain’t,’ and he’s trying to be, and in the Ivy Club, if he’s trying to be the new Mark Birley, he shouldn’t give up his day job.” Furthermore, having an official Club at the Ivy is making some regulars worry that the real Ivy will seem even less like the unofficial club it used to be.

But is that such a terrible thing either? Henry Wyndham, the gregarious chairman of Sotheby’s Europe, believes that Caring has tapped into a positive social development: “London has become this extraordinary cosmopolitan place, where we were very insular probably 25 years ago, and now London is absolutely brimming and booming with ... people from other countries living and enjoying London life. There’s less of a class system. There’s a much better atmosphere.” In other words, isn’t it time the Brits stopped getting their knickers in a twist over the thought of other people having fun? The new reality, at least at the Ivy, might have been summed up when Christopher Biggins— who’d just been named “king of the jungle” on the reality show I’m a Celebrity . . . Get Me out of Here!—returned, victorious, from the Australian jungle. He reports, “The First night I came back, I went to the Ivy, and I got a standing ovation!”

Right now, the restaurant that many Londoners consider the most fun is the one Caring truly did himself, Scott’s. It was a “rotting bomb,” as Caring puts it, and he invested $10.5 million in transforming everything about it. “It’s probably the best restaurant in London right now,” Wyndham says. “And it’s the most fun restaurant, it’s got a real buzz to it, and that’s his own creation.”

As for Caring’s inroads into the U.S., he’s opening up Soho Houses in Miami, Chicago, and Los Angeles—on the top two floors of a high-rise on Sunset Boulevard—with Soho House founder Nick Jones, who still retains 20 percent. (Caring’s sons both work for Soho House in London.) Caring and Jones will also be opening the second branch of their Italian restaurant, Cecconi’s, in the building where Mortons used to be, on Melrose Avenue. (After nearly 30 years, the famed Hollywood restaurant has closed.) Caring may also bring Scott’s over to L. A., he says. “And if you’re going to bring over Scott’s, why not one or two of the other brands?”

In New York, he’s opening Le Caprice in the Pierre hotel. And, most notably, he has been doggedly trying to buy the empire of fellow Brit Keith McNally, who owns Morandi, Pravda, Lucky Strike, and Schiller’s Liquor Bar, in addition to Pastis and Balthazar. Encapsulating the Sex and the City age, they are not necessarily known for their food, but certainly for their buzz—combining the right location and the right look. The goal, again, is expansion. Caring wants to replicate Balthazar in London, Los Angeles, and Chicago.

But in McNally, Caring couldn’t have found a tougher customer. “By nature I have an intense dislike of chains and sister restaurants. Even the phrase appalls me,” McNally told me. He has turned down many offers to sell, including “an incredible” one from Las Vegas mogul Steve Wynn. “But lately I’ve seen so many copies of my places... that I’m coming round to thinking it’s not the worst thing in the world.” And after meeting Caring, who came to him with no “bullshit” or phony flattery, McNally felt he was someone “I could work with. Or for, I should say.” It also helped that McNally fell in love with Caring’s places in London, especially Scott’s and the Club at the Ivy. “Unfortunately, I like most of them more than my own!” he reports. “In fact I’d like to buy them.”

Still, for the moment, McNally is holding off on a deal, despite Caring’s “very, very generous” offer, which according to another source is about $100 million. Though Caring assured him he could retain as much involvement as he wanted, McNally is not ready to have his staff ultimately answer to someone else. And there’s another nagging concern. “If I duplicated Balthazar or Pastis, I’d be ripping the soul out of the original. I’m not the kind of person who goes to Nobu in Moscow because I like the Nobu in New York. Quite the opposite—I’d never go to another Nobu again anywhere/”

Whatever McNally’s reservations may be, Caring hardly has time to wring his hands over them. He has plans for a new hotel in London called Bed and Brasserie. He’s expanding a chain of mid-priced bistros called Cote. He wants to start a “spectacular worldwide concierge” service to take on the needs of anyone who’s a member of one of his clubs. He’s looking into buying some luxury fashion labels, and getting into wine production.

And there may be more in Caring’s future than even he himself has considered. Upon hearing the vague rumor that he was interested in buying New York’s Four Seasons restaurant, I called up co-owner Julian Niccolini to ask about it. He hadn’t even heard of Richard Caring. Who is he? Niccolini wanted to know. What is he about?

“Interesting,” he said at last. “I think he should give us a call.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now