Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

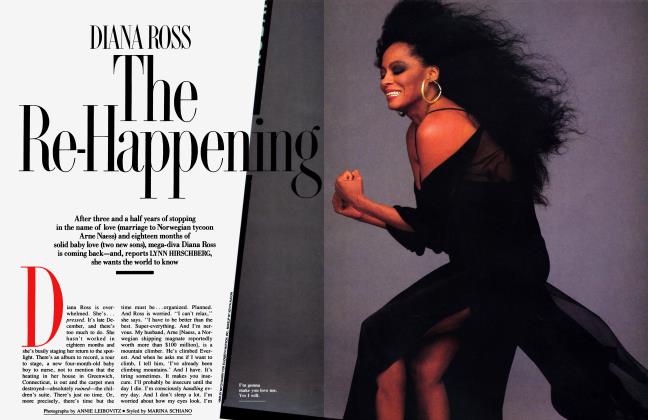

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowQuentin Tarantino is the love child of cool-guy movies and 1970s pop culture. The writer-director burst onto the scene with his brilliant, bloody Reservoir Dogs, followed up with True Romance, and hopes to be No. 1 with a bullet when his latest film, the star-filled Pulp Fiction, opens in August. LYNN HIRSCHBERG hangs out with the film junkie who is mainlining American noir

July 1994 Lynn Hirschberg Annie LeibovitzQuentin Tarantino is the love child of cool-guy movies and 1970s pop culture. The writer-director burst onto the scene with his brilliant, bloody Reservoir Dogs, followed up with True Romance, and hopes to be No. 1 with a bullet when his latest film, the star-filled Pulp Fiction, opens in August. LYNN HIRSCHBERG hangs out with the film junkie who is mainlining American noir

July 1994 Lynn Hirschberg Annie LeibovitzQuentin Tarantino is sitting on his couch making a list of action sequences. He is tall and rumpled and handsome in an appealing, big dog sort of way, and he bends over the pad of paper like he's taking a final exam. Except, he's happy. He's all enthused about the idea of making this list of the best action sequences of all time, and he's writing furiously, visualizing gunfights and car chases and guys with their heads bashed in. "Hmm," he says, writing down "Shoot-out in The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly." "Oh, yes!" he exclaims, recalling the opening sequence of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

He scribbles away ("The truck chase in Road Warrior!" "The warehouse scene in 8 Million Ways to Die"). "What's so great about those sequences," he explains, "is that you forget you're watching a movie. You forget you're breathing. You're just, like, 'Wow.' " Tarantino concentrates a second. He likes this task because it is about movies, and not only does Tarantino arguably know more about movies than any other person on the planet, but his interest goes beyond mere knowledge: Tarantino has the zeal of a true believer. Quite simply, he is in love with movies—they are not only what he does but, to a great extent, what he is.

And like all great obsessives, he strives for order ("The restaurant shootout in Year of the Dragon," "The chain-saw scene in Scarface"). There are so many scenes, characters, plots, MOVIES coursing through Tarantino's brain at any given moment that he has had to invent a structure. Categories. Genres. Lists.

Lists of action sequences, lists of best first-kiss scenes, lists of favorite movies. The list of Tarantino's 10 favorite movies changes all the time, but three remain constant: Taxi Driver, Blow Out, and Rio Bravo. "When I'm getting serious about a girl, I show her Rio Bravo," he says, "and she better fucking like it."

"The mark of a cool actor is, after you see his performance, you want to act like him."

Past the exalted three, there are thousands more, all organized by genre. "There are 'Two Guys and a Girl' movies, like Jules and Jim, Bande à Part, and A Girl in Every Port, by Howard Hawks," Tarantino explains, becoming increasingly animated. "Then there's 'A Bunch of Guys on a Mission' movies, preferably W.W. II. The best are Where Eagles Dare or The Guns of Navarone. Then there's 'How I Grew Up to Write the Book' movies, like Imaginary Crimes. There's 'The Teacher I'll Never Forget' genre, which is To Sir with Love and Dead Poets Society. Then there's 'Mother Nature Goes Ape-shit' movies, like Frogs and Willard. Not really Jaws, which is more of a horror movie, but Night of the Lepus. Then there's 'I Married a Whore but Can't Stand to Watch Her Work' films, like Mona Lisa, and 'New Faces' movies, like Dark Passage, which are about plastic surgery."

And so on. So many genres. And each one informs Tarantino's own work. Reservoir Dogs, his highly acclaimed screenwriting and directorial debut, is a "Heist Gone Awry" movie. And his next film, Pulp Fiction, which just won the Palme d'Or at Cannes, is an anthology movie. But in both cases there's a twist: Tarantino's scripts have a way of reworking the classic genres. The plots and characters are familiar, but Tarantino's structure and dialogue transcend any category. His style is unique, half rooted in some long-ago cool-guy world that may never have existed except in movies, and half stuck in the 70s pop culture that has resurfaced in the 90s. In Tarantino's world, movies of the past make the rules, but he longs to bend them, to push beyond the boundaries of any genre.

Which does not diminish his obsession with practically every other movie in the universe. If prompted, Tarantino will launch into soliloquies on topics ranging from the brilliance of The Last Boy Scout to the genius of JeanPierre Melville to the underappreciated art of director Kevin Reynolds.

"Kevin Reynolds is going to be the Stanley Kubrick of his decade," Tarantino proclaims. "I think so. Fandango is one of the best directorial debuts in the history of cinema. I saw Fandango five times at the movie theater and it only played for a fucking week, all right? Five times I saw it! And Kevin Costner is so great in that movie. To me, the mark of a really cool actor is, after you see his performance, you want to act like him. All right, I wanted to dress like Kevin Costner. I started talking like Kevin Costner. I wanted to wear a filthy tuxedo and sleep and piss and barf and drink and sweat in a car going over the desert. He made a filthy tuxedo look like the coolest thing to wear.

"Oh, I just thought of another one," he says, scribbling down "The shootout in the whorehouse in Rolling Thunder." "Did you see it? It was great! It's a 'Revenge' movie," he explains. "Which means that the guy's happy for the first 20 minutes and then they kill his wife or his dog or something and they fuck him in the ass and he wants revenge. And then, for the rest of the movie, he gets it. He fucks them back. In Rolling Thunder, William Devane and Tommy Lee Jones go to a Mexican whorehouse and create a war. You really want them to get revenge. It's the same way in John Woo's A Better Tomorrow. You really hate the bad guys and you really want the good guys to kick some ass. But in Rolling Thunder, they kick more ass than you could even imagine. Most movies let you down in that way, but this is ass-kicking Nirvana." He pauses. "That scene will change your life," he says. "Absolutely, fucking change your life."

"Violence is a color in his palette. Some work with musical numbers—he works with violence."

He isn't what you'd expect. Not from his movies. Tarantino's films—Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction, which he wrote and directed, and True Romance and Natural Born Killers (directed by Oliver Stone and also due out in August), which he scripted—are dark, bloody affairs full of brilliant tough-guy dialogue and violent exchanges. Discussions are usually held at gunpoint and nearly everyone dies. It's a severe world, menacing and dangerous, but laced with a quirky sort of humor: in Pulp Fiction, two hit men on their way to blow away some drug dealers debate the psychosexual ramifications of foot massages; in Reservoir Dogs, a sociopathic killer dances to "Stuck in the Middle with You" before slicing off his victim's ear.

The humor in Tarantino's films often comes out of these juxtapositions, but it is also a function of his remarkable dialogue, which borrows stylistically from films such as His Girl Friday and other classic comedies. Yet Tarantino's scripts are not dated—he has taken that learned sensibility and turned it upside down. So that in Pulp Fiction a romantic first-date scene is at once modern and stuck in some sort of screwball-comedy time tunnel:

MIA: Now I'm gonna ask you a bunch of quick questions I've come up with that more or less tell me what kind of person I'm having dinner with. My theory is that when it comes to important subjects, there's only two ways a person can answer. For instance, there's two kinds of people in the world, Elvis people and Beatles people. Now Beatles people can like Elvis. And Elvis people can like the Beatles. But nobody likes them both equally. Somewhere you have to make a choice. And that choice tells me who you are.

VINCENT: I can dig it.

MIA: I knew you could. First question, Brady Bunch or The Partridge Family?

VINCENT: The Partridge Family all the way, no comparison.

MIA: On Rich Man, Poor Man, who did you like, Peter Strauss or Nick Nolte?

VINCENT: Nick Nolte, of course.

MIA: Are you a Bewitched man, or a Jeannie man?

VINCENT: Bewitched, all the way, though I always dug how Jeannie always called Larry Hagman, "Master!"

MIA: If you were Archie, who would you fuck first, Betty or Veronica?

VINCENT: Betty. I never understood Veronica attraction.

MIA: Have you ever fantasized about being beaten up by a girl?

VINCENT: Sure.

MIA: Who?

VINCENT: Emma Peel on The Avengers. That tough girl who used to hang out with Encyclopedia Brown. And Arlene Motika.

MIA: Who's Arlene Motika?

VINCENT: Girl from sixth grade, you don't know her.

Pulp Fiction is not all this breezy. (In fact, this exchange appears only in the shooting script; it was cut from the final film.) In Tarantino's movie universe, things veer off in extreme directions. This date between Mia and Vincent, for instance, ends in a near death by heroin overdose. Yet the violence functions in the same manner as the dialogue—it's another way to establish character, to create a world. "Violence is a color in Quentin's palette," says Stacey Sher, co-executive producer of Pulp Fiction. "Some work with musical numbers—Quentin works with violence. But unlike most filmmakers, he shows its impact. In his movies, violence is hyper-real. It's not just a style thing."

It is, instead, a movie thing. When Reservoir Dogs came out in 1992, Hollywood was eager to hail Tarantino as the voice of his generation. The movie was appearing at film festivals at the time of the L.A. riots, and somehow the movie and its director, who had actually grown up in South-Central L.A., became emblematic of the real-life violence. But it was only timing—Reservoir Dogs had nothing whatsoever to do with racial tension. It is mostly about trust and a kind of existential code, a brilliantly structured, elegantly plotted story about five guys who are doomed. Its biggest influence was not the violence on the six o'clock news but the violence in the six o'clock movie.

Tarantino's is a cool, cold movie world, so it's a (pleasant) surprise when he doesn't turn out to be a hepcat in a black suit and shades. Sitting on the set of Pulp Fiction, he is dressed in baggy corduroys, a T-shirt, and a scruffy suede baseball jacket. He has a kind of constant alertness: he is hyperaware of the moment, the way, say, a kid is when he's playing with electric trains or expounding on his favorite issue of Spiderman.

It's a chilly evening, and tonight the movie is filming at a large ultramodern house nestled in the Hollywood Hills. Pulp Fiction is three interlocking stories, anchored by one main character, Vincent Vega, played by John Travolta. In the scene to be shot tonight, Vega is taking his boss's wife, Mia (played by Uma Thurman), out for dinner. This is meant to be her home and it is spectacular. The house is positioned on a cliff and has breathtaking own-the-world views of L.A.

As the crew sets up inside the living room, Tarantino perches on the edge of a patio lounge chair. It's an extremely relaxed set, more like a party, with cast and crew members floating about, stopping by to say hey to Quentin. "Bruce Willis was great," Tarantino says of another Pulp Fiction star, not famed for his on-set ease, who has finished filming his scenes. "Everyone loved him. Every week he raffled off four pots of $50 each for the crew. So Uma said, 'I can beat Bruce like that. I'll raffle off a blow job.'" Tarantino laughs. "That would have definitely beat 50 bucks."

Tarantino started writing Pulp Fiction as soon as he had finished postproduction on Reservoir Dogs. Even before principal photography was completed on it, Reservoir Dogs was the talk of Hollywood. "I had read Dogs and loved it," recalls Stacey Sher, "but I hadn't met him. And then I went with a friend to the premiere of Terminator 2 and we're all hanging out and my friend says, 'I'm about to make your night—here's Quentin Tarantino.'" Shortly after that, Sher helped Tarantino secure the rights to the Stealers Wheel classic "Stuck in the Middle with You" ("If I couldn't get that song, I wouldn't have made the movie," he says now), and—without having seen Reservoir Dogs—Sher, the president of Jersey Films, offered Tarantino nearly a million dollars to write and direct his next movie. "You just knew," she says. "You knew he had a vision. He hadn't directed anything, but you knew."

After Reservoir Dogs came out, he went to Amsterdam and started writing Pulp Fiction. ("There was a Howard Hawks film festival there," he remembers. "It was one of those God things.") Tarantino writes the old-fashioned way: in longhand. "You can't write poetry on a computer," he states emphatically. "So I go buy a 250-page notebook and three black felt pens and three red felt pens, and I say, 'These are the pens I'm going to write Pulp Fiction with.' It's very romantic."

After a year of writing the script in hotel rooms all over Europe while promoting Reservoir Dogs at festival after festival, he finished the third and final draft and handed it in to Jersey Films. They had set Pulp Fiction up at TriStar Pictures, but upon reading Tarantino's screenplay the studio reportedly became nervous about making the $8 million movie. "It's a wild script," says one TriStar executive, "and although a lot of the writing was thrilling, it was just too dark." Soon after TriStar put Pulp Fiction in turnaround, Miramax picked it up, making it its first major acquisition since being sold to Disney. It will undoubtedly be the first Mouse movie with romance, heroin, and anal sex.

Tarantino writes old-fashioned movie dialogue—the kind of speeches and banter and chat that actors love to say. Pulp Fiction attracted stars such as Bruce Willis and John Travolta, who are huge in the international film market. That meant that, even before shooting began, Miramax could sell Pulp Fiction in every European territory and already be in the black. "That's very uncommon, but everybody wanted to do Pulp Fiction," says Miramax co-president Harvey Weinstein, who has just signed Tarantino to a two-year first-look deal.

And they worked for very little. Bruce Willis's fee on Die Hard 2 was as much as the entire budget of Pulp Fiction. "I think it cost me money to do this movie," says John Travolta. "Around $30,000. I wanted to stay in a different hotel, so I said, I'll add money to the per diem. But it was well worth it. Quentin's script is like Shakespeare."

Seeing as how Travolta is a 70s icon and the star of Blow Out, Tarantino was thrilled by the prospect of casting him in Pulp Fiction. "As much as I like John Travolta, I couldn't bring myself to watch some fuckin' talking-baby movie," Tarantino says, referring to Look Who's Talking I and II. "But I've seen everything else he's done. And he's one of my favorite actors." It's a great part for Travolta: he gets to be funny and cool and tragic.

"Travolta is great," Tarantino practically shouts. Mid-exclamation, he is interrupted by Eric Stoltz. He's also in Pulp Fiction, but he isn't working tonight, just hanging around the set, soaking up the atmosphere. "You're still in costume," Tarantino says, greeting him warmly. Stoltz is wearing a stained Speed Racer T-shirt and baggy jeans. He looks as if he hasn't shaved or bathed in days, possibly weeks. "The bathrobe I wore as Jimmy," says Tarantino, who has a small part in the movie, "I did everything in that bathrobe. I ate. I drank. I masturbated in that bathrobe." Stoltz nods. They talk some more about how long you can go without changing your clothes ("I think about five days," says Stoltz, as if he has given the matter great thought), until a crew member tells Tarantino he's wanted on the set.

Inside the all-white glass-and-steel living room of the house, Travolta is preparing for his entrance. He is dressed in black and has hair extensions, which are pulled back into a long, glossy ponytail. He looks more adult than he did in the 70s—age has subtracted some of the lushness from his face—but he is still quite handsome. He hasn't lost that movie-star thing.

Tarantino walks over to Travolta and they huddle for a moment. This scene has already been blocked, but Tarantino just wants to say hello and good luck and all that. As an actor himself, he understands the value of contact with a director. Tarantino is practically the only director working today who doesn't use a video monitor. "I don't trust monitors," he explains almost vitriolically. "To me, when directors bring monitors on their sets, the monitor directs the movie. You can't see a performance in a monitor. Just fuckin' forget it. The magic in the eyes—you can't get that from a monitor. You have snow and grain. Howard Hawks never used a monitor. A lot of good movies were made without them.

"And besides," he continues, "every actor, I don't care who the fuck it is, will look at the director after he finishes his scene and you need to be there. You need to be there—not the back of your fucking head across the room buried in the monitor."

Tarantino smiles. Unlike most of the human race, he is not plagued by worry. He is a doubt-free zone. So what that he has made only one movie and that everybody else in the business, people with a lot more experience, all use monitors and think they work fine—well, fuck that. It's just not Quentin. He doesn't care that we are not back in the 30s, or even the 70s, when video technology was not a part of the filmmaking process. He's a romantic.

"You're old-fashioned," says Stoltz, overhearing Tarantino's anti-monitor diatribe. "But that's why we love you."

"Ah," replies Tarantino, clapping Stoltz on the shoulder. "I'm also right, you know. I know I'm right."

He was named to be famous. "I wanted a name that would fill up the entire screen," says Connie Zastoupil, Tarantino's mother. "A multisyllabic name: Quen-tin Ta-ran-ti-no." She was only 17 when her son was born, and she named him (the name would have been the same had he been a girl) after a character Burt Reynolds played in Gunsmoke, Quint Asper. "It's a big name," Zastoupil says now. "And I expected him to be important. Why would I want to have an unimportant baby?"

"I hated school," Tarantino recalls over a plate of Thai honey duck in one of his favorite haunts, a pleasantly divey L.A. restaurant called Toi. "School completely bored me. I wanted to be an actor. Anything I'm not that good at I don't like, and I couldn't focus on school. I never got math. Spelling, I never got spelling. I was good at reading. And I was good in history. History was like a movie. But a lot of things that people seemed to learn really easily it took me years to learn. I didn't learn how to ride a bike until the fifth grade. I didn't know how to swim until I was in junior high school. I didn't learn how to tell time until the sixth grade. I could do the 30s and the o'clocks, but when it got to anything more intricate than that, I was perplexed." He smiles. "To this day, I can't tell time that well. And when everyone's telling you you're dumb and you can't do what everyone can do when they're seven, you start to wonder."

Despite his failure at school, Tarantino always had an unflagging sense of faith in his own abilities. "He just had his own agenda," Connie Zastoupil says. "From the beginning of his life, Quentin only wanted to devote his waking hours to what amused him."

Instead of going to class, Tarantino went to the movies. His mother, a wildly progressive parent, had taken him to Carnal Knowledge when he was five ("It bored me") and a double bill of The Wild Bunch and Deliverance when he was six ("That scared me—you couldn't take me camping ever"). From the time he was seven, every Monday night, his stepfather would take him to the movies.

He started writing scripts in the sixth grade, which he flunked, including an after-school special inspired by his massive crush on Tatum O'Neal. By ninth grade, he was barely attending school. "They called my mom, and when she asked me, I said, 'Yeah, I quit school,"' Tarantino recalls, spearing a piece of duck. "A couple days later, she said, 'I'm gonna let you quit, but you have to get a job.' "

He started acting in community theater (switching from his adoptive name to his birth name of Tarantino) and, at 16, lied about his age to get a job as an usher at the Pussycat Theatre in Torrance, California. "I hated porno movies," Tarantino says. "To me, it was the most ironic situation: I finally got a job at a movie theater and it's a place where I don't want to watch the movies."

At 22, after a string of other jobs, Tarantino began working at Video Archives in Manhattan Beach, Southern California's premier video store. "People think I learned about movies because I worked there," he says. "But I worked there because I knew about movies." At Video Archives, movies played on the monitors all day long. The staff wasn't particularly interested in the tastes of the customers—if they felt like watching Pasolini, Pasolini it was.

At Video Archives, Tarantino met others like him, specifically fellow film obsessive Roger Avary, another aspiring director. "When we first met we had a great competition," Avary recalls. "We hated each other. It was 'Who knows more?' And he won. Quentin is a database. I decided a long time ago to give up the fight. I decided instead to lead a life."

These two fancied themselves the 80s American version of the 60s French New Wave. "Not to sound like too much of an egomaniac," says Avary, "but Quentin is to Truffaut as I am to Godard." Tarantino violently disagrees. "He's not Godard," he nearly spits. "No way. I'm more like Godard than he is. If anyone's Truffaut, it's Roger. But I'm definitely Godard."

Actually, Tarantino's more like Scorsese, but whatever. Avary was right on one point: he spotted the enormity of Tarantino's ambitions from the jump. "For Quentin," he says, "it was either grand success or video-store clerk. There was nothing in between." For a while, it looked like the latter. Tarantino was having no luck with filmmaking: his first movie, a half-completed screwball comedy called My Best Friend's Birthday that he had worked on for four years, just didn't jell, and his acting career was largely stalled, although he did appear as an Elvis impersonator on an episode of The Golden Girls. "It didn't matter," Avary recalls. "Quentin always thought he would make a big splash. He'd studied so many careers, he knew how to do it."

After five years at Video Archives, he quit to devote himself full-time to filmmaking. "Working there was like my college," he says now, finishing his duck. "I gave them almost all my 20s." Tarantino looks pensive for a moment. "When I left I knew I was going to be successful," he says. "I didn't know how long it would take, but I knew. I always knew."

'I saw your forehead across the room!" It's 10 P.M. on a Tuesday night and Tarantino is having dinner at the Olive, practically the only perpetually cool restaurant in L.A., and tell-all writer/former producer Julia Phillips has spied him. "You're Quentin!" she says, turning on her high beams. He is very gracious—she did, after all, co-produce Taxi Driver, one of his holy trinity. "It's so nice to meet you," he says. "I love Taxi Driver." Phillips nods. She is a small, very tan woman with spiky white hair. "The best experience of my life," she says. "Seriously, the best." Phillips takes Tarantino's hand. "You made me want to make movies again," she says gravely. "When I saw Reservoir Dogs, I wanted to make movies again."

At this, Tarantino does a sort of Gomer Pyle gee-gosh-golly-thank-you and Phillips says her good-byes. He is visibly pleased, but not surprised: ever since Reservoir Dogs, he has become used to this kind of fuss. Tonight, there has been a steady stream of fans, friends, and colleagues stopping by his table. "This never happens this much," he says as a girl who once interviewed him stops by to say, "I've just finished a script for Simpson and Bruckheimer and I couldn't have done it if I hadn't seen Dogs." By the sixth such interruption, Tarantino, who is unflaggingly polite, starts to make jokes. "Kubrick just paid his respects," he says. "And John Milius came by and said how I wrote Apocalypse Now. Did you know I'm the one who told Kubrick not to name the computer 'Marvin'? I told him 'Hal' would be a much better name."

"One day you're pushing videos and the next day you're having books written about you. That changes you."

In context, the adulation makes perfect sense. The Olive denizens appreciate Tarantino's combination of success and credibility: he is walking, talking proof that you can violate the rules and flourish in Hollywood. He never compromised; he did not sell out in any way. To many, Reservoir Dogs represents the best of the independent-film world, and now he is being courted by the studios on his own terms. "I know how hard it is to make a great film," Phillips had said. "And you made a really great film."

It wasn't so simple. By 1989, Tarantino had written two scripts, True Romance and Natural Born Killers, which no one wanted to let him direct. Through a friend, Tarantino met a former dancer and actor named Lawrence Bender, who had produced a low-budget slasher movie called Intruder. "It was July 4, 1989," Bender recalls. "Quentin was at the end of his tether with these two projects. And he said, 'I'm gonna make this movie Reservoir Dogs' He had the title, but he hadn't written it yet."

The rest is legend in the indie world: Tarantino wrote the script in three and a half weeks; Bender flipped over it and asked for a year to raise the money. Tarantino said, "No way. I'll give you two months with an option for one more month." Bender agreed and went to his acting teacher, who was friendly with Harvey Keitel. He loved the script. "You have no idea what a thrill it was to hear Harvey Keitel's voice on my answering machine," Bender recalls. Once Keitel signed on, other actors followed. Eventually, Bender raised $1.6 million. They shot Reservoir Dogs at a former funeral home in Highland Park, California, and before Tarantino was even finished with editing, the movie was being hailed as a small masterpiece.

Reservoir Dogs was a sensation—the first coffeehouse action movie. Meaning, people who thought they were too cool for Lethal Weapon would see this film. Reservoir Dogs was an action film for nihilists—it spoke to Kurt Cobain (who thanked Tarantino on In Utero) and movie buffs alike. "This gentleman does not do what I consider to be the action genre," says Lawrence Gordon, who produced 48 Hrs., Die Hard, and many of Tarantino's favorite action films. "But I thought Reservoir Dogs was about as intense a film as I've ever seen. I could barely watch it. It was great, but too fucking real. I had to close my eyes, and I rarely close my eyes."

"People wanted to meet me after Dogs," Tarantino says. "I was a pet." It was from 0 to 50 overnight: Tarantino took his movie to festivals and openings and, in the process, did more than 400 interviews, answering everything from "Did Mr. Orange die at the end?" ("Yes") to "What does the title mean?" (He refuses to say, but his mother provides the answer: "He was talking to one of his girlfriends and she said, 'I want to go see Louis Malle's Au Revoir les Enfants.' Quentin said, 'I don't want to see no reservoir dogs. ' And that's where the name came from.")

Not surprisingly, the question most asked about the movie concerns the violence. "It's a big drag," Tarantino says now. "When they start to talk about the violence, even in a nice way, it's like 'Get out of here.' I've stopped defending it. At first I thought that Pulp Fiction would be my get-it-out-of-my-system crime film. After all, I don't want to be known as 'the gun guy.' But then I thought, Fuck everybody. What if, after Pulp Fiction, I come up with another great idea for a crime movie—I'm just going to do it."

Tarantino's incredible sense of self-confidence buoyed him through the post-Dogs feeding frenzy. The festival circuit is an onslaught of flattery, sycophancy, and blather—it can puff up the head of any director. "Going to Sundance was, for me, like being on some strange psychotropic drug," says Roger Avary, whose film, Killing Zoe, was screened at the festival this year. "You're in an alternative reality. Everyone is telling you how great you are. It's very seductive, but I lost myself—it was like doing crack for a week. And that was only one film festival. Quentin went to festivals for a year. That's got to affect you. Look, one day you're pushing videos at the store and the next day you're having books written about you. That changes you. It has to."

Maybe. But Tarantino seems remarkably at ease with his fame. It's as if he was always expecting this to happen—it was just a matter of when. And it's bought him leverage. "The good thing about being spoiled early," he says, "is you can't go backwards. You can't accept less." He pauses. "What I'm proudest of is my perseverance," he says as a fan wearing a huge medallion bops over to the table. This guy praises Tarantino to the moon ("You're a god!'''). Tarantino thanks him enthusiastically. "I remember what it was like," he says as the guy bops off. "I'm not so far away from that."

This is what Quentin Tarantino likes to do: sit on his couch. "I'm a lazy bastard," he says. "Making a movie is really hard work, and when it's done, I'm like 'See you later.' "

Tonight, Tarantino is sitting on his couch and watching Night Call Nurses, a Roger Corman production from the 70s. "It's a sexy version of Three Coins in the Fountain," he explains, going into genre mode. "Corman made about five of these movies and Night Call Nurses is my favorite. The 'Nurses' cycle is a subgenre. It's really a T&A movie. Other T&A movies are cheerleader movies and beach movies. The dark subgenre of T&A movies were Corman's 'Women in Prison' movies."

Tarantino's one-bedroom apartment is a pop-culture playground. There is little furniture—a chair, the aforementioned couch, and a coffee table which is covered with videotapes, scripts, and magazines. A 50-inch TV dominates one side of the room. "For a year and a half I did not have broadcast TV," he says. "I used my TV like a monitor." On the mantel are dolls—an Ilya Kuryakin doll from The Man from U.N.C.L.E., a John Travolta doll, a Boy George doll—and some awards, including two bronze horses from the Stockholm film festival. "I'm big in Sweden," says Tarantino.

There are framed vintage movie posters hanging everywhere, a large bookshelf in the dining room ("I would study Pauline Kael's reviews like class assignments"), and an even larger bookcase in the bedroom which is packed with videotapes. Tarantino collects lunchboxes, preferably from TV shows of the 70s, and he has a closet full of board games based on TV and movies. Neatly stacked are Thunderball and I Spy and Baretta. There's also a Grease game and a Welcome Back, Kotter game. "I played myself in both games," recalls John Travolta. "And I won. Both games." Tarantino is thrilled at the memory. "Playing with John was cool," he says. "It's my dream to do a Reservoir Dogs game."

The light in the apartment is dim, and it has the comfortable feel of a cool, cluttered cave. "Let's watch the movie," Tarantino says. "I had a total fantasy about working for Roger Corman," he says. "I thought, I'd be really good and do everything and then Roger Corman would say, 'Quentin, you can direct a "Women Behind Bars" film.' And I'd make the best 'Women Behind Bars' film ever. That was my fantasy, but he didn't have a job available."

Night Call Nurses is a fine example of the Corman oeuvre—like all his films there's a mix of sex, nudity, and political consciousness. Tarantino is quite taken with the brunette nurse. "There are always three," he explains. "A blonde. A brunette. And something ethnic." He seems to be equally captivated by the screenplay. Tarantino howls when the brunette nurse tells an ardent suitor, "Maybe if we went someplace else, someplace where I felt more comfortable, more at home," and her would-be boyfriend counters with "Like your home, for example?" "Great line!" Tarantino exclaims. "I can use that!"

"Quentin loves popular culture," says his friend Roger Avary. "It extends to lunchpails, games, TV shows, and especially movies. He knows everything about popular culture. But his greatest strength is his greatest weakness. He is only interested in pop culture. For instance, he would refuse to see The Bear. Because he hates bears. It's about nature, and nature has nothing to do with pop culture. The one problem people have with Quentin's work is that it speaks of other movies, instead of life. The big trick is to live a life and then make movies about that life."

Tarantino vehemently disagrees. "To me, the danger of making movies about movies is when Hollywood makes the same movie over and over again—a black cop and a white cop, but this time in Tijuana. Or it's Die Hard on a bus. And I can enjoy those if they're done well, but they're not original. There's always been a ton of movies that make movie references. But I'm making movies I haven't seen before. Except for rare moments, I'm superconscious not to be analytical when I'm writing or directing. I only want it to apply to the work after the fact."

Night Call Nurses has rewound, and Tarantino has popped in another tape, a documentary on Roger Corman. But it's getting late—around two A.M.—and he has to work on Pulp Fiction's sound mix tomorrow, so he can't watch all the way through. He pushes the stop button on the VCR. "We'll watch it later," he says, sounding distracted. He is paying attention to what is now on the TV screen. It's a Japanese monster movie being shown on Mystery Science Theater 3000. Two girls, one in a bikini, are being chased through the streets. "I know this movie," he says, as if there was any question. He watches for a moment. It doesn't matter how absurd this film is, Tarantino is riveted. It's a movie, after all. What could be better?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now