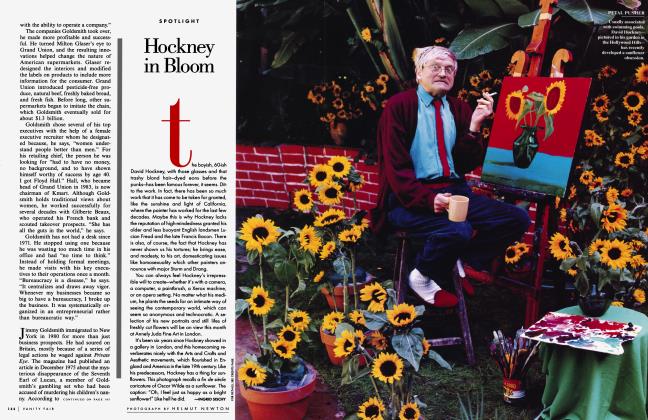

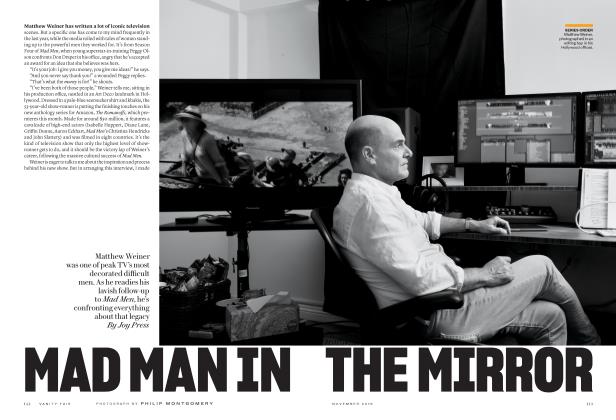

Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMarietta Tree: SERIOUS MONEY

How many blue-blooded blondes who hobnobbed with the Duke of Windsor and captivated such men as John Huston and Adlai Stevenson would exult in the frustrating legwork of U.N. politics? Only Marietta Tree, who until her death in August championed human rights by day, and by night opened up her elegant home to a Who's Who of politicos and power brokers, networking for the social good. MARIE BRENNER reports on the last of New York's great drawing-room diplomats

"Never did I think I would walk into what looked like the first scene of 'Marie Antoinette Comes to Versailles.'"

t the last dinner party she ever gave in her splendid peach rooms, Marietta Tree greeted her guests as if nothing were the matter. She gave her customary little gasp of pleasure and said, "Hello, beauty!" and "How wonderful you look!" Her voice was both cultivated and childlike, a breathy vibrato. Marietta Tree was a great blonde vision, an aristocrat with memorable cheekbones, an exalted carriage, and an almost otherworldly serenity. She adored parties, and the small details of this dinner last June were as flawless as ever. Marietta's brown leather seating chart with its tiny paper flags indicating placement was by the door; her waitress offering champagne was wearing a starched black bombazine skirt reminiscent of New York in an earlier era.

It was a warm night, and she had thrown open the bay windows of her Sutton Place apartment to the great lawn and beyond, to the shimmering necklaces of lights on the Queensboro Bridge, which spans the East River. "Wouldn't it be wonderful if our city's bridges were lit?" Marietta had remarked years earlier to the then mayor, John Lindsay. "New York could seem so much like Paris!" Lighting the bridge that now twinkled in her back windows was so like Marietta Tree, for she was one of the rare people in life who appeared to believe that if she did something for the world, the world might come back to her.

Everyone dressed up to go to Marietta Tree's house, and this night was no exception. The men in their dark suits were like glamorous black shadows, as if they expected Jock Whitney to burst through the door at any moment to set the standard. The drawing room glittered, the lighting illuminated her shelves of good books lining the west wall, her portrait by the English society painter Molly Bishop, her fine porcelains, antique mirrors, worn brocade sofas, and stacks of leather albums filled with the clippings of her accomplishments over the decades.

Later, when they thought about the evening, several friends remarked that Marietta had looked thinner and a bit wan, but they passed it off as fatigue, for her voice was light and bright, and her laughter filled the house. It was impossible to believe that she was sevenfyfour years old. She was dressed exquisitely in ivory gauze and wore dangling earrings, which were "crazy Indian junk," as she said. Marietta often dressed like a torch singer; she told one of her brothers that her real career desire had been to belt out "Mr. Sandman" at El Morocco. Even in her seventies, she invariably wore gold shoes under her ball gown, or a plunging neckline, or black fishnet hose. She was a sensualist with the soul of a bluestocking. She was said to have had discreet affairs with John Huston and Adlai Stevenson, but her relationships with men were mysterious, as was the way she lived. It was thought that she was tremendously rich, but in fact she had comparatively little money. The one good emerald she owned she had recently sold, as if, at this point in her life, she was determined to return to the plain ways of her forebears.

Politicians, Oxford dons, bankers from Abu Dhabi, theater people, and Pakistani ambassadors attended her dinners, as did playwrights, journalists, and editors, for she had an able and impatient mind and thrived on serious conversations. "It is time for 'gen con,' '' she often said, by which she meant general conversation. She would turn to a guest such as her friend Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and say, "Arthur is just back from Washington, where he had a fascinating conversation with the president.'' Only Marietta Tree could get away with this and not seem autocratic. "There is no music more beautiful than a lot of informed people shouting over public affairs past and present," she wrote to her friend Shirley Clurman.

There was, however, no "gen con" or shouting this night in June. After dinner, the guests moved into the drawing room and Marietta settled into a green velvet window seat. Inexplicably, she began to talk about the past. This too was out of character, for Marietta was a woman who was deeply personal about impersonal matters—politics, issues, world affairs—"fixated on the future," as her daughter the writer Frances FitzGerald phrased it.

"The first time I was kissed, I was desperate to know what it would be like," she said that night. Franklin Roosevelt was president then, and Marietta had marched with a boy out onto the lawn at her grandmother's large house on Mount Desert Island, off the Maine coast. She said she imagined that at that moment her life was about to begin. "I closed my eyes tight and I waited and waited. When the boy finally kissed me, it was so disappointing! I wanted something more. I don't know what I wanted, but I did want more." The story was small and rather inconsequential, but her guests laughed appreciatively. Then Marietta Tree looked out at her lights and smiled.

The day of her last party, she had remained in bed until dinner in order to have the strength to get through the evening, for she was determined that no one except her older daughter should know that she had inoperable cancer. She had been reared, her brother George said, to be "a Christian gentleman," thus did not want to be a burden, and, more, could not admit to herself or anyone else that her body had let her down. "She was trying desperately not to sink, which was the running theme of her life," Frances FitzGerald said. In the last year, a close friend had taken her home from a party. "How are you?" he asked. "Very, very lonely," she replied, much to his astonishment.

"Good God, Marietta, I have never seen such a rejecting family as yours," Ronald Tree told her.

Marietta Tree managed to have immense power in New York without anyone's being quite sure where it came from. She was a Peabody, a Boston Brahmin, the daughter of Puritans and rectors, an exemplar with perfect manners who had been imbued with the notion of public service. Her grandfather Endicott Peabody had been Franklin Roosevelt's mentor. All her life, Marietta Tree was a devoted Roosevelt Democrat. As a schoolgirl of fifteen, she was at Hyde Park with the Roosevelt family on Election Night in 1932. Her devotion to fairness was honed during the Depression. She had first-class instincts and believed that work was, as she told her daughters, "the real fun in life." Marietta Tree was an egalitarian; she loathed snobbism and fought prejudice her entire life.

As a young glamour girl during the war, she once sat next to the Duke of Windsor at a dinner. She was barely out of the rectory then, twenty-five years old, working as a researcher on the editorial page of Life magazine. In her spare time, she was working to integrate Sydenham Hospital, on the border of Harlem. At dinner, Marietta bombarded the Duke with questions. "Sir, could you describe to me the process of the Salic law?" "Did the laws of British royal succession start with the Empress Sofia of Hanover?" Windsor gave her, she wrote, "a piercing look," told her to wire his mother at the palace, and then asked, "Why are you asking me these extraordinary questions?" "Because, sir, we are doing a story on the rise of British democracy in connection with the British general election next week." "Well," said he, "if the Socialists win, that is the end of democracy in Britain." Marietta later wrote to her parents:

I can say without boasting that I gave him a lot of information, as I think him a stupid as well as a prejudiced man. He is psychotically anti-Communist and also anti-Semitic. He has got good manners and therefore a certain charm and on the whole it was an interesting evening to examine the fabric of his mind and how it got that way.

Once, her brother George Peabody asked her to explain power. "Always tell the truth, but not all of it," she told him. She was a contradictory figure who combined gravity with gaiety. In the 1950s, she was a passionate advocate of civil rights. Her congressional district in New York was then controlled by a legendary Republican reactionary named Frederick Coudert. Marietta ran for state committeewoman of the Democratic Party, a seat formerly held by Dorothy Schiff, owner of the New York Post, and won. She worked tirelessly to defeat Coudert by giving progressive speeches condemning his isolationism. She was also a standard-bearer in Brown v. The Board of Education, the 1954 Supreme Court ruling on school integration, and spoke at length against "apartheid in America,'' as she later called it. She helped to write the plank on civil rights for John Kennedy's 1960 campaign.

Kennedy rewarded her by naming her to the Human Rights Commission at the United Nations. Eleanor Roosevelt had drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a document covering a whole range of covenants, from asylum to unjust imprisonment to the treatment of refugees. It fell to Marietta Tree to persuade dozens of emerging nations in Africa to adopt these principles and incorporate them into legal treaties. Marietta was brilliant at this, traveling all over Africa and America giving speeches and persuading obstinate caucuses to see it her way.

For Marietta, the frustrat ing work of the United Nations was never drea ry or beside the point. She found a strange kind of glamour in the endless diplomatic re ceptions, for she had ac cepted the tedious assignment not for self-promotion but to contribute to the commonweal. She fought a move by the Ukrainians to gain power on the Human Rights Commission. Her State Department adviser Marten van Heuven described her combination of "girlishness and feistiness," which was perhaps the key to her success in extending the human-rights agenda into the Third World. But she never lost her feminine appeal. In Geneva, assisting in negotiating a treaty, Marietta enlisted her State Department aides to help her find a good earring in the elevator shaft. A Swedish diplomat had been so overcome with her that he had lunged for her, she told them laughingly, and van Heuven recalled that Marietta "thought nothing of having us get her earring back."

At times Marietta Tree seemed as flawless as a painted set. She was consummately social, and had mastered the gracious entrance, the witty aside, the admiring word. With her immense discipline, she knew how to keep her figure and her appointments. She also knew how to preserve friendships by ignoring feuds and feigning optimism at all times. She couldn't stand being called a great lady or a grande dame, for she believed it implied that she was frivolous. "What do I have to do not to be called a socialite?" she once asked me.

However social her instincts, she remained determined to give back to the world. She worked for six months in Albany in 1967, helping to draft a possible new constitution for New York State. She became a member of the Trusteeship Council at the United Nations overseeing territories such as Micronesia. She became a factor in American political life, picking up honorary degrees and trusteeships at colleges and on councils. When she was in her fifties, she returned to college and took a degree in city planning. She became a partner in an international design firm and fell in love with its senior partner, Lord Llewelyn-Davies, a visionary city planner "who thought twenty years ahead," according to one of his associates. Outside Adelaide, Australia, she guided the firm's plans for a model city, and, near Melbourne, its plans for a teaching hospital which would service the working class. She traveled often to Teheran, before the fall of the Shah, to oversee the development of a two-thousand-acre model city with the national library in the center of town. She worked on a rehabilitation strategy for Times Square and helped on urbandevelopment projects in Pittsburgh and San Antonio. Privately, she helped support African students in this country and often sent checks to people in trouble who asked for her help.

She was determined to live in the largest arena possible. Not a highly original thinker, she was intuitive, a fast study who knew how to captivate powerful men. Marietta was admirably never embarrassed about her affinity for the opposite sex. As one of the first women to belong to the Century Club, she attended a black-tie dinner for members. There was only one other woman in a sea of two hundred men. "Don't you find this ratio deplorable?" the other woman asked Marietta. "I find it perfect," Marietta replied.

She was commandingly tall and had an extraordinary body; she was one of those rare women with an elongated torso, a tiny waist, and an enormous bosom. When she put on a Madame Gres draped chiffon gown, she resembled Athena, but her face had small, perfect features. She radiated intelligence as well as a cool inaccessibility. In 1960, John Hustoh cast her in The Misfits to do a sexy goodbye scene with Clark Gable at a train station in Reno. Marietta looks awkward embracing Gable and ing, "Remember, I have the secondbiggest laundry in St. Louis.'' Huston's camera could not capture her sexual magnetism.

One night in 1960 at her grand house in Barbados, Marietta was with Arthur Schlesinger and Adlai Stevenson as Stevenson labored mightily, writing and rewriting the speech he planned to give at the 1960 Democratic convention. Marietta supported Kennedy; she was desperate for Stevenson to throw his delegates to Kennedy, but she was careful not to hit too hard, Schlesinger remembered, for she knew Stevenson and Kennedy did not get along. She never forced the issue as Stevenson endlessly rewrote into the night.

Marietta Tree was active in New York in a naive and agreeable time when many Democrats were elitists who argued about integration, the Cold War, and McCarthyism. She lived in a vast house on East Seventy-ninth Street provided by her second husband,

Ronald Tree, an Anglo-American investment banker who was a grandson of Marshall Field and who had once been a British M.P. Tree was often mystified by Marietta, who used her house "as an extension of the Lexington Democratic Club,'' recalled Russell Hemenway, an officer of the club. "There were receptions and fund-raisers several nights a week, and Ronnie never knew what he would walk into.'' "Who are all these rotters?'' Ronnie Tree once demanded when he saw his house filled with strangers.

In the mornings, Marietta would wake up in her immense canopy bed in her beautiful third-floor bedroom with French doors that overlooked her garden. Her personal maid, Alice Butler, would enter Marietta's room early and wake her by opening the silk curtains; then she would draw her bath. Marietta had her breakfast in bed and then took care of her morning correspondence, dictating notes to go out on her fragile blue tissue stationery from Smythson's, with an old-fashioned telephone and her number engraved in the upper-left comer. She carried on extensive correspondence with senators and presidents and wrote frequent charming notes to her closest friends, who included Evangeline Bruce, Jacqueline Kennedy, Susan Mary Alsop, Mary Warburg, Polly Fritchey, and Kitty Carlisle Hart.

At the height of her career, Marietta would leave her house by nine A.M. to be briefed at the U.N. She was a dogged student of diplomacy and could talk for hours about the question of Chinese representation or banning the bomb. Arriving at the U.N. in her black wool suit and triple strand of pearls, she would race to the delegates' lounge and carry on two conversations simultaneously, in French and Italian. If Stevenson was obtuse about the necessity of winning blocks of votes with social pleasantries, Marietta knew how to cultivate the delegations, particularly those from Latin America and Africa. She would open her house night after night for diplomatic receptions, inviting a mix of celebrities and internationals who spoke the same languages as her other guests. Her English butler, Collins, would pass champagne on an antique silver tray while the delegates gaped at the Trees' eighteenth-century furniture and the Coromandel screen they had imported from Ditchley Park, their former stately home in England. Marietta was adept at finding out how the delegates intended to vote, using the same technique she would later teach her two daughters about dinner-party etiquette. "Ask them about their childhoods," she said, and that simple trick enabled her to hear, as she put it, the delegates' hidden agendas "almost like a dog hears supersonic sounds.''

Years later, she was able to use that same talent as a member of the CBS board. She once returned from a month at her house in Tuscany to discover Bill Paley feuding with the head of the network, Thomas Wyman. Her first day home, she set about visiting every board member in order to coolly assess the situation. Roswell Gilpatric, a CBS board member, recalled that she was close to Wyman, but angry that he was attempting to sell CBS to Coca-Cola, thus robbing it of its independence. At the climactic board meeting, she spoke first and movingly, calling Wyman "a fine man" who did not have the "taste and ability" to run CBS. According to Ken Auletta in his book Three Blind Mice, Marietta said, "I think the company should remain independent and that Bill and Larry [Tisch] should take over the company."

Marietta bloomed in crowds, as if she were hungry for affection. Despite years of psychoanalysis in the 1950s, she could never transcend a dislike of being by herself. Her brother Sam Peabody was always surprised when she confided in him about her lack of selfconfidence, but she transformed her particular pathology into a strong record of public service. "Analysis gave me such energy!" she told her brother George. "I much prefer going to a boring dinner than being alone with a good book, because the book is always there, but the dinner will never come again," she told a friend.

All her life, Marietta Tree had an inordinate fear of death and illness. "I do not want to die!" she used to tell Susan Mary Alsop ferociously, as if she believed that by the force of her discipline she could stop the passage of time. When her sister-in-law Judy Peabody decided to dedicate her time to the care of AIDS patients, Marietta told her, ''I think it is wonderful what you are doing. Just please never tell me about it." She was terrified of death, perhaps because the first death she ever witnessed was that of Adlai Stevenson. Walking with Marietta in London in the summer of 1965, he suddenly said, ''Keep your head high. I am going to faint." He collapsed, and Marietta bent over him, trying desperately to revive him with mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. As he fell, his briefcase came open; pink classified cables flew all over Grosvenor Square.

Marietta Tree spent her life with men with a passion for discretion, men who knew how to keep secrets, just as she kept their secrets and many others. She had learned to keep her own counsel in her childhood, and that lesson served her well in her love affairs. She rarely told her own daughters much about her life. ''I knew there were many questions I could never ask my mother," Frances FitzGerald told me. She said it was ''inconceivable" that she would have curled up on her mother's bed and asked her about her long romance with Adlai Stevenson. "My mother called that kind of thing 'toe curlers'—questions that were so embarrassing they curled your toes! But that was the kind of family she came from. They never talked about anything! And certainly not sex."

'Good God, Marietta, I have never seen such a rejecting family as yours," Ronald Tree used to tell Marietta, according to her brother George. It was difficult for anyone in the Peabody family to earn parental approval. Marietta and her four younger brothers had the same taut bones, a similar laugh, a passion for the irreverent, a need to contribute to society, and a subtle resentment of one another. They grew up in a crowd with more than thirty first cousins, but their parents were not affectionate. As the only daughter, Marietta appeared to have suffered more than her brothers: Endicott, known as "Chub," Sam, George, and Malcolm junior, whose nickname is Mike. Perhaps as a result, she became deeply competitive with them, except for Sam, whom she felt close to. "We all competed with each other for what little affection there was," Sam Peabody told me. "My brothers and my cousins on both sides of the family were absolutely amazed by Marietta, and also very jealous of her. They tried to catch up with her, but she was impatient and had other things to do." She was the powerful sibling who had a difficult time sharing center stage. Almost unwittingly, she often made her brothers feel insignificant.

"I always assumed that Adlai Stevenson was in love with my mother,"Frances FitzGerald said.

Marietta Tree was the firstborn child and the first grandchild of her generation of the great Peabody clan, whose original fortune came from merchant sailing ships. Her father, Malcolm Peabody, was an Episcopal bishop; her mother, a Parkman from Boston, was so unpretentious that, once, when she was taken sailing on a vast yacht, she called out to everyone she passed, "It's not ours! It is not ours!" Another time, she slammed on the brakes of her car when she realized that her son Endicott was holding hands with his girlfriend in the backseat. "I had such an awful relationship with my own mother, I was determined not to repeat it with my daughters," Marietta once told a friend.

Marietta Tree's mother was, however, a powerful role model. A stem matriarch and a passionate advocate of civil rights, she was once arrested at a demonstration in St. Augustine, Florida. At the time, Marietta was at her great house, Heron Bay, in Barbados with her husband, Ronnie. "Don't you dare leave Florida unless you get arrested! Otherwise there is no point," Marietta shouted at her seventy-four-yearold mother on the telephone. Several days later, a telegram arrived during lunch. "Oh, good news, everyone! Mrs. Peabody has been released from prison!" Ronnie Tree announced at the table. As it happened, the Queen Mother was a guest that day. "Mrs. Peabody released from jail? Oh dear, she will be so disappointed," the Queen Mother said, according to Marietta's brother Sam.

As a child, Marietta often felt isolated, and learned that her complaints would not be heard sympathetically. She had to assert herself from an early age if she wanted attention. "Go ahead and hit me with a stick!" she shouted at one brother. "I dare you! You won't do it." When her brother took her up on the dare, she began to sing so that no one would see her cry. "She had an expression we all picked up—'sib riv,' " George Peabody told me. "She was the most generous person in the world, but only on her turf. If there was any suggestion that / was getting any power, then the needle came."

The "sib riv" played out in small ways and large ways. When her brother Mike was deputy assistant secretary of HUD, he learned that his sister was meeting privately with his assistants, "trying to get her projects through." "They would come in all starry-eyed and say, 'Your sister is just wonderful!' I had to blast her for going behind my back!" When Endicott was running for governor of Massachusetts, Marietta did "very little" to help his campaign, according to several members of the family. "She didn't like it that Chub was getting in the national arena—that was her turf," George told me. She also was opposed to his conservative views on the Vietnam War. "Endicott was fighting the Kennedys in Massachusetts, and they stuck together as a family. He was upset that he didn't feel' the same support," Sam said. When George became a management consultant, Marietta said to him, "None of us quite understand what you do." Even Sam was not immune from "the needle." "I learned not to ask her for favors," he told me. "Let's make a list of the four or five real stars in our family," she said, as an adult, to George.

Marietta's childhood winters were spent in Philadelphia at the rectory in Chestnut Hill, her summers in Northeast Harbor, a lovely town of New England lobstermen and aristocrats off the coast of Maine. Northeast Harbor was only thirteen miles, but a psychological world, away from Bar Harbor, the elegant summer colony favored by Pulitzers and Morgans. "To the Bishop and Mrs. Peabody, Bar Harbor was a dangerous place! The bishop thought of it as entirely populated by very decadent rich people who spent their mornings lying by a large heated swimming pool at the Bar Harbor Club waiting to drink their first martini before lunch," recalled Susan Mary Alsop, who as Susan Mary Jay became Marietta's first and closest friend.

Marietta's grandfather Endicott Peabody was a rector, who founded the Groton School with financial support from J. P. Morgan. He ran it for fiftysix years, educating Roosevelts, Dillons, and Harrimans in the classics and the benefits of cold showers, using up much of the Peabody fortune in the process. He was "a monster," one of his grandsons told me, a frightening figure who treated his own son, Marietta's father, and his grandchildren as "Groton first-formers. Sex was verboten, smoking, drinking—all those things! Divorce was out of the question."

On her mother's side, her grandmother Parkman, a rich Bostonian, was a considerable scholar who knew classical Greek. A trustee of Radcliffe College and a glamorous rebel, she waited until she was thirty-five to get married, after having had "scores of famous affairs," according to Mike Peabody. After having five children, she decided child rearing was not for her. She turned the responsibilities for her children over to her firstborn child, Marietta's mother, and resumed a love affair. Not surprisingly, Marietta's mother resented her ever after.

She was determined to live in the largest arena possible.

Continued on page 288

Continued from page 220

Marietta was subjected to "prayers every morning, grace at every meal, and Sunday school,'' Sam Peabody said. "But damn it, the Peabodys stood for something!" A family expression was "a Peabody or a nobody." During the Depression, Marietta and her brothers were often taken to call on the poor. Politics was discussed constantly, as well as the family history, comprising all sorts of worthies, including early abolitionists. Jane Addams, a founder of Hull House, was a frequent visitor to Northeast Harbor and a close friend of Marietta's mother. Mrs. Peabody was active in the Girls' Friendly Society, but when her granddaughter Penelope Tree, Marietta's second child, married a South African musician, she was very upset. "Oh, come on, Mother, you went to jail over civil rights," Sam Peabody told her. "1 believe in justice, not intermarriage," Mrs. Peabody snapped.

Almost from birth, Marietta confounded her mother. "They couldn't believe it! Mrs. Peabody once read to Marietta and me a bit of a diary she kept," Susan Mary Alsop told me. "It was written in 1921, and I remember it very vividly: 'Malcolm and I find it increasingly difficult to comprehend Marietta. She is enchanting and everybody is crazy about her. . .but she is also very independent-minded! Happily, we are going up to Groton next week and Malcolm has already written to his father to ask if he would see Marietta and talk to her and help us understand.' "

Marietta bucked her parents constantly. When she was a teenager, her father lectured her about smoking. "During the argument, Marietta lit up a cigarette! I remember my father hit the ceiling!" George Peabody said. But Marietta had forged a strong ally in her grandmother Parkman, for they were kindred spirits. Marietta and her grandmother had "a common enemy," Frances FitzGerald said. "That had to be very difficult for my grandmother—their enemy." Marietta's alliance with her grandmother appeared to infuriate her mother. " 'Mapa,' as we called her, worshiped Marietta," Mike Peabody said. "They were so much alike, and they understood each other. Mapa would do anything for Marietta." She even counseled her on her techniques with men. "Always remember what fragile creatures men are," she said. "They are even more scared than you."

By the time Marietta was a teenager, "every boy in Bar Harbor was in love with her," according to William McCormick Blair Jr., the former U.S. ambassador to Denmark and the Philippines, who was a close childhood friend. "When Marietta used to come to Groton to visit her grandfather, the dining room would stop." Her parents did everything to try to tamp down her spirit, even insisting that she leave the dances at the Bar Harbor Club long before the band stopped. She was seething inside, according to Susan Mary Alsop, but never complained except about one thing. "When she would drive in with a date, her father would be on the porch with a watch, and Marietta was never allowed to linger in the car. That infuriated her!"

She was educated at St. Timothy's school in Maryland, then went to finishing school in Florence, where she perfected her French and Italian. She returned and expressed a desire to get a degree in political science. Her father insisted she attend the University of Pennsylvania, because she could remain at home, although her younger brothers were allowed, she recalled bitterly, "to go to Harvard, to do anything they wanted."

It was 1939. Marietta was in the middle of her junior year at Penn. Susan Mary Jay was engaged to Bill Patten, who introduced Marietta to his friend Desmond FitzGerald—"Desie," as he was called. He was a Republican lawyer, "devastatingly handsome" and "intolerant of fools," Sam Peabody said. The Peabodys were suspicious of his family, for they were from Long Island and spoke with clenched teeth, as if they were "social people." Marietta's parents were furious when she fell in love. "They called him second-rate," Frances FitzGerald said. Later, he would become deputy director of the C.I.A. Perhaps to escape her parents, Marietta determined to marry before she finished school. "My mother used to say to me that her whole childhood could be summed up with a song from Porgy and Bess: 'There's a Boat Dat's Leavin' Soon for New York,' " Frances FitzGerald said.

They married on September 2, 1939, while Hitler was invading Poland. The guests listened to the radio all during the reception, and it was obvious to everyone at Marietta Peabody's wedding that their lives would soon be turned upside down. It was less obvious that the war would begin to free Marietta FitzGerald, as it freed scores of other women.

A few years ago, Marietta Tree started to draft her memoirs. "Write down what you really think about everyone," Arthur Schlesinger told her. "Tell the truth." It was an impossible assignment, for Marietta always camouflaged her opinions in the gentlest of casings, even phrasing most negative thoughts as questions. She was able to write only a few pages of detached and girlish prose. Some of the observations she made about her life were quite telling, however. For Marietta FitzGerald, the war was "heady liberation."

I don't think anyone realized we were pioneers of the feminist revolution. My new friends were trade union officials, politicians, reporters, movie directors, and I was particularly fortunate in my new women friends. Mary Warburg, Minnie Astor (later Fosburgh) and Dorothy Paley (later Hirshon). . . . They led me into a world a long way from the rectory in Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia, and introduced me to Valentina clothes, Ed Murrow, the Rockefeller Institute, Orson Welles, house parties, mahjongg, a good skin doctor, the Urban League, smoked salmon at "21," interior decoration, psychoanalysis, Thomas Mann (the man), "The Game," Bill Hearst, mascara, the American Veterans Committee, Edith Sitwell, impressionist and fauve paintings.

She was twenty-three when she arrived in New York with Desie. She couldn't cook, knew almost no one, and immediately became pregnant with Frances. "Oh, she was so dowdy then!" her friend June Birge said, but she was determined to learn. She registered for classes at Barnard and pushed her pram in the park with her new friends Mary Warburg and Ethel Roosevelt, the president's daughter-inlaw, whom she knew because Franklin junior was a Groton boy. When the war began, she and Mary Warburg went to work for Nelson Rockefeller, taking visitors from Latin America all over New York. Even then she was passionate. Touring a prison infirmary, she tugged at Warburg's sleeve. "Look at that marvelous gangrened toe!" Another time, at Riker's Island, Marietta was served "the most disgusting scrambled eggs with the inmates," Warburg said. "How can you eat this?" Warburg asked her. "Someone has to," Marietta said.

She was hired by Life magazine as a researcher. She wrote in her memoirs, "After the Personnel Officer of Life Magazine telephoned me to say that I had been chosen. . .1 sang, hugged myself, danced around the room, and must have frightened the people below with my entrechats. ... It was my first real job. ' '

Her first day at work, she looked up her friend Mary Warburg's name in the Life research stacks. "Marietta called me and said, 'You know what they have you down as? A socialite! How could they?' To be called a socialite was the most disgusting, nauseating thing in the world!"

No longer dowdy, Marietta was soon discovered to be a major beauty. Horst photographed her for Vogue. With Desie posted in the Far East, Marietta was quickly the toast of the town. When her brother Mike came down to visit from Groton, he answered the telephone. "This is Tony," a man said. "Who is Tony?" Mike asked Marietta. "Anthony Eden," she said. "We're going to dinner tonight." Eden was then the British foreign secretary, in New York to drum up support for the war. Marietta wrote her parents of parties she was giving: "Great fun—had the Astors, the Bennett Cerfs (he's a publisher), the Warburgs, Covarrubias (a Mexican painter), Barbara Mortimer [later Babe Paley]... and the Larry Lowmans (he is in charge of CBS television)—everyone on their toes and they didn't leave until 3. Feel a little drawn today."

What did her parents make of such behavior? Attempting to rein her in, as always, they wrote to her, counseling her to get pregnant when Desie came home on leave. Marietta was furious.

Thank you in a way for your two letters ... counselling me to be affectionate to Desie and to enlarge my family. I am 28 years old.... What I would like every once-in-awhile is a little approval from you both—as a matter of fact that is what I have always wanted all my life from you, and never felt—or certainly rarely felt that I had it—as compared to what you give Endicott and Mike, for instance. You have done so much more for me than most parents that I have no cause for complaint and overflow with gratitude—but I do get approval from others (even in the family) and can't be entirely wrong—and naturally I would rather have it from you two than anybody else—except Desie.

She was beyond her parents' stem bromides now, beginning to live life on the pinnacle. One night Bill Paley invited her to dinner with Ed Murrow and the English publisher Lord Beaverbrook. Beaverbrook was then the czar of British arms and airplane production, with a reputation for "force and a wicked charm used to manipulate people," she wrote. That night, the German army had advanced to the suburbs of Moscow. "If Hitler defeats the Russians, which he probably will," Beaverbrook told them, "we are in for a thirty-year war." After V-E Day, Marietta encountered Beaverbrook again. Fearlessly, she reminded him of his prediction. "He turned purple," she wrote, "and said, 'I never said any such thing.' The Life researcher, always trying to be accurate, [said], 'Oh, yes, Lord Beaverbrook, you did say that, and Bill Paley and Ed Murrow are witnesses!' "

She shared an office with Earl Brown, the Time Inc. expert on city politics, baseball, and unions. "He was the first black that I had ever met and I was sweatily polite to him to show how unprejudiced I was," she wrote. One day Marietta lost a phone message for him from the union leader Walter Reuther. Brown yelled at her, and she yelled back. "But in my anger," she wrote, "I suddenly saw a person . .. not a black man. ... I never saw his color again nor did I see anybody's color after that." She was a woman of her class and her era, and had been reared to believe that unions were "corrupt or Communist." At Life, she was made aware that the Newspaper Guild had fought for the benefits she enjoyed. She joined and became the shop steward, collecting dues and attending meetings, where she "learned to outmaneuver the few Communists in the union. Afterward, I generally went dancing at El Morocco, and enjoyed the contrast of white plastic palms, champagne and dancing with men in black tie and uniforms."

Early in the war, Madge Kingsley, the wife of the playwright Sidney Kingsley, called her. "Come meet us at '21,' because we have two extra men for dinner. ' ' Mary Warburg went along. "We got to '21' and there was John Huston! There was immediate electricity between John and Marietta.... I wasn't so lucky. The other extra man was an embalmer." Huston was the son of the actor and singer Walter Huston, and had just made The Maltese Falcon. Marietta FitzGerald was oblivious; in fact, she had never heard of him, she told Lawrence Grobel, the author of The Hustons. "I couldn't think of anything to say, so I said, 'Are you any relation to Sam Houston?' He thought for a bit. 'Who's Sam Houston?' " Huston had the dark charm of a rogue, the complex personality of his favorite character, Sam Spade. At the time he met Marietta, he was carrying on a love affair with Olivia de Havilland, whom he had directed in In This Our Life.

He was taken with Marietta, and later said, "She was the most beautiful and desirable woman I had ever known." He would become, according to Dorothy Paley Hirshon, "the passion of her life. She was radiant when they were together." Huston exuded danger and masculinity, although he was quite circumspect with Marietta when they were with friends.

Marietta Tree appears to have been consistently drawn to men who could expand her dimensions, yet not enslave her with their demands. No one could have been a better teacher than Huston. He swept her along into his New York; they stayed out all night drinking at P. J. Clarke's while he told her amazing stories, including the entire plot of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. He took her to meet Lillian Heilman, whom she adored, and each weekend he was in town he would follow her out to Long Island, where she often went to stay with her close friend Minnie Astor.

On Long Island, Bill and Dorothy Paley were right down the road at their estate, Kiluna Farm. At that time, Dorothy Paley set the tone in New York; she was a dark, brainy beauty on the international best-dressed list and as passionate about interventionist politics as Marietta, much to Bill's discomfort. Marietta and Dorothy became fast friends; they worked together to open a nursery in Harlem. "We painted like crazy," Dorothy Paley Hirshon told me. "And that was not the sort of thing she liked." But she showed up when she promised, as she would all her life.

Marietta FitzGerald fit in perfectly in her new world with John Huston, but she was, from time to time, overcome with guilt when she thought about Desie in the Burma theater, for she "had a very high idea of duty," Dorothy Hirshon told me. Her friends knew that Huston was desperate to marry her. He had begun to pressure her to tell Desie about their relationship. Marietta resisted, for she was not "head over heels in love" with him, and she was well aware that he was impossible as "marriage material," in Mary Warburg's phrase, for he had a whole string of women.

Her marriage to Desie, however, had been destroyed by the war. "I had been waiting for him to come back—I mean literally every day—and when he finally did, it was wonderful and just as I imagined it would be, and then, boom, the divorce," Frances FitzGerald told me. Having learned what it meant to be truly free, Marietta was not about to return to the staid life she envisioned as the wife of a Park Avenue lawyer. "Now I was expected to give up my job, give up my new friends, as Desie naturally wanted to see his old friends," she wrote, adding selfmockingly, "and the last straw, give up half of my closet space."

As she had once escaped the rectory through her marriage to FitzGerald, she appeared determined to get away from her husband. When Desie came home on a leave, she told him about John Huston. "I didn't hear from her for three days," Huston remarked. "I could see that she'd been through an ordeal; her face was drawn and her eyes were swollen. Desmond had agreed to give her a divorce, but only on condition that she see an analyst and undergo therapy before starting proceedings."

FitzGerald was cleverly attempting to buy time, but his ploy did not work, for one weekend at Kiluna, Marietta met the man she would ultimately marry, Ronald Tree. Tree was twenty years older than Marietta, polished and extraordinarily discreet. Tree's wife, Nancy, of the Virginia Langhome family, was a niece of Lady Astor; she was, like Ronald, an AngloAmerican who had taken on the ways of her adopted country. She had filled the seven reception rooms and twenty-four bedrooms of their eighteenth-century home, Ditchley Park, with important furniture and "had a way of making a room look so old and so perfect," William Paley once told me. Later, she was a principal of the design firm of Colefax and Fowler.

Tree had the same chiseled features and slicked-back hair as Desie, but he was international and very, very rich. He had been reared as a generalist, and believed that he would live out his life in the style of an English lord, occasionally writing a book of architectural history. Tree's immense estate in Oxfordshire was the retreat of Winston Churchill, Brendan Bracken, the British Cabinet, and the London smart set—the David Nivens, Noel Coward, Diana and Duff Cooper. And, more than John Huston, Tree shared Marietta's passion for politics. The Office of War Information sent Tree on a speaking tour to help shape public opinion in favor of the British; Archibald MacLeish dispatched him to Harvard to speak to the Nieman fellows, according to Tree's memoirs, When the Moon Was High. For Marietta, Tree must have seemed incredibly romantic, sweeping into New York from harrowing journeys on the Pan Am Clipper from Lisbon; once, he was trapped with an alleged Vichy traitor for three days by bad weather. Inevitably, he would call Marietta when he arrived in the city, for his marriage to the witty but high-strung Nancy Tree had fallen apart.

One day at the end of the war, a package was delivered to Mary Warburg's apartment. "It was a box from Ronald Tree. I thought, How strange. I opened the box, and inside was the most beautiful blue-lacquered Faberge box. On the lid was an 'M'. made from diamonds. I thought, Ronnie has gone out of his mind! Later, I learned that that box was for Marietta.

... But until then I had no idea that anything was going on.''

Marietta was overcome with guilt when she left Desmond FitzGerald. Her divorce, according to her brothers, would become a central fact of her life, for it pitted her finally and definitively against her entire family; there was no turning back. The divorce would as well color her future relationship with her daughter, for she knew that Frankie worshiped her father, yet she moved her an ocean away. "I felt my life was over when she married Ronnie," Frances FitzGerald told me.

Marietta's father was now the bishop of central New York in Syracuse. One day Marietta announced dramatically that she was arriving to discuss "the situation." "A plane flew over," Sam Peabody recalled, "and I can remember my father saying, 'That's Marietta's plane.' He was dreading it! My father was closeted with Marietta in his study for what seemed like days. My mother was furious! She was saying, 'There never has been a divorce in this family and there never should be one!' Not only did she announce that she was going to Reno to be divorced but that she was going to marry Ronald Tree! This was outrageous!" Marietta suffered tremendously, for her parents enlisted her brothers to move against her. "I remember writing a letter to her saying how terrible this was. Endicott did the same thing. Marietta wrote me back, saying how hurt she was by my letter. And that, of all people, she depended on me for support. I wrote her back and said, 'I'm with you,' but I don't think she ever forgave Endicott, and that was the beginning of the split."

There is a wonderful picture of Marietta Tree as a bride posing in front of one of the great doors of Ditchley. She was smiling and looked joyous, very Hollywood, as if she were playing a role. Her petticoats caused her skirts to billow out. The caption in the scrapbook read, "Owner!" Far from the fairy tale the picture implied, however, the new mistress of Ditchley arrived to find a gloomy and hostile environment.

Nevertheless, it was very grand. She wrote in her memoirs of their arrival:

The huge front door was open revealing part of a hall of height, depth and grandeur beyond my experience and imagination. [There were] busts of gods and ancient heroes, bosomy beauties, huge statues of classical heroes, a painted ceiling of gods and goddesses, [with] acanthus leaves and eagles and flags strewn all over them....

Each time Marietta made a suggestion, the housekeeper would say, "Well, the first Mrs. Tree always liked to have it done this way."

Lined up from the door and reaching far back into this huge, pale and gilded space were the indoor staff who served in this palace numbering over thirty people.... Never did I think I would walk into my next house with my beloved and my sweet little daughter, a pale and bewildered six-year-old, into what looked like the First scene of "Marie Antoinette Comes to Versailles."

Marietta Tree was then twenty-nine years old, thrust onto a vast estate of more than three thousand acres, run in preWorld War I-style grandeur in the grim winter of 1947. Rationing was in effect; there was little fuel or food. The Trees relied on the farm for supplies. Marietta was without domestic skills; she was a magazine girl who liked to talk politics. Her first assignment as the mistress of Ditchley was to hire "a cook for the servants," according to Sam Peabody. Frankie "had to eat her dinner alone on a tray in one of those great gloomy halls," Dorothy Hirshon remembered. "She was a very unhappy child." Her school in Oxford had little heat. "We used to warm our pencils in a fire so our hands wouldn't freeze," she told me. Marietta had little support from her parents, who had forged a new closeness with Desmond FitzGerald, even encouraging him to purchase land in Maine.

Additionally, the acerbic and popular Nancy Tree remarried and mounted a campaign against her former husband's bride. Lady Astor, her aunt, called Marietta "Mrs. Reno Tree," according to Sam Peabody. "It was Nancy Tree's house! Everything in it was Nancy Tree. She had done the whole house... the servants... everything! It was not easy. She was the intruder!" said Dorothy Hirshon. The chief housekeeper was loyal to Nancy Tree. Each time Marietta made a suggestion, she would say, "Well, the first Mrs. Tree always liked to have it done this way." Marietta later wrote that the woman "was so like the sinister housekeeper in the movie Rebecca that I was determined to get rid of her as soon as I learned her job myself."

It was said that Marietta opened up a drawer in her dressing table on her first night at Ditchley to discover a note from Nancy Tree: "Who's the puss in my boots?" Sometimes during weekend house parties, Nancy Tree would appear and make a terrible row, wanting one or another of her pictures or urns back, according to Susan Mary Alsop. Overwhelmed, Marietta's puritan character caused her to be overly solemn with the sardonic British upper class, and she was an instant social flop. Taken to visit Henry Moore by the art critic Sir Kenneth Clark, Marietta stared at Moore's monumental statues in his garden. "Could you tell me what you mean by these images, Mr. Moore?"

Her first encounter with Winston Churchill was "frightful," she wrote. She had no idea that Churchill did not address women at the table. She drank "three glasses of champagne and [it made me] feel warmer and more relaxed." Churchill decried "the rationing system after the war, which he condemned as a drag on the free market." Marietta, with her populist heart, challenged him, saying it was unfair that the rich could luxuriate in "self-indulgence." "I was John Calvin addressing the sinners," she later wrote. "Goon, giveitto him," Sarah Churchill, his daughter, whispered in the silence. "The argument was dropped like a lead balloon," Marietta wrote, and for the rest of the meal she stared "remorsefully. . .at my plate."

In her misery, she set a pattern that would remain all of her life. She became a woman who solved her problems by assiduously doing her homework. If Ronnie's interest was furniture, she would learn it. If the British upper class wanted to be frivolous at dinner, she would not insist on talking about the machinations of the Labour Party and the new prime minister, Clement Attlee. Perhaps as an antidote to this passivity, she began to make her own set of friends. "I remember the first time I met her, in Paris in 1948," Arthur Schlesinger told me. "She was wearing a beautiful scarlet dress. She was so ravishing, and she was starved for news of America. The election was just over, and all she wanted to do was talk politics. I fell madly in love with her."

Ronnie needed her more now, for he had been swept out of Parliament by the triumph of the Labour Party. The new British tax laws crippled him, for as an American in England he was forced to pay double tax, and, worse, his old friend Anthony Eden had done nothing to help him create a position for himself after the war. Tree felt betrayed, according to friends, for he had backed Eden during the Munich crisis and had gotten no reward. "It was quite lazy and selfish of Anthony," a friend said. Tree felt as if he were losing altitude; he made the decision to sell Ditchley and recoup in America. But before they left, Marietta and Ronnie gave one last great ball.

It was July 1949. Marietta was just pregnant with her second daughter, Penelope. She wore billowing peach chiffon and looked glorious, for in her two years in England she had turned her former antagonists around. The night of the ball was astonishingly warm. The great trees of Ditchley were illuminated with hidden lights, a new French technique at the time. "It was the most beautiful ball I had ever attended," Susan Mary Alsop said. The terrace was filled with titles, including young Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip, who "stood by themselves" for much of the evening, according to Sam Peabody.

Marietta had invited every American friend she had in London, including a man from Northeast Harbor she hadn't seen in years. "This man drank a bit too much of Ronnie's excellent champagne and. . .he lurched onto the dance floor and cut in on the future Queen! It was to die!" Susan Mary Alsop said. "Immediately, one of the members of the royal household rushed to Marietta and said, 'Mrs. Tree, this guest must be removed.' Supremely loyal, Marietta answered, 'What do you mean, remove him? He is an old friend of mine. He is a beautiful dancer, and I am sure that Her Majesty is enjoying herself very much. I only hope that he will dance with me!' Then she turned away from this dastardly woman." After midnight, her guests ate cold salmon, delicious cheeses, and salads, and Susan Mary remembered Marietta feeling wistful. "I'm going to be so homesick for England back in New York. What am I going to do without this wonderful place and our lovely life?" she asked her old friend.

She was entering the fourth phase of her life, the New York years in which she would become a public figure, but it would take her some time to find her way. Returning to New York in 1949, she complained of "low energy" and developed psychosomatic illnesses from stress. Marietta had to start all over again in New York; she was a rich woman who had once worked as a fact checker, married to a man who had no defined work. "Ronnie loathed New York," Sam Peabody said. "He had many friends, but no position or focus." At first, Marietta felt compelled to take on a superficial role as her husband's hostess, "trying hard to amuse Ronnie with constant entertainment," Peabody said. Marietta adored the pace of New York and the intelligent conversations, but Ronnie was avid to escape for much of the year to Barbados, where he built a Palladian retreat on the water. Not surprisingly, Marietta "would go crazy after two weeks there," for she couldn't stomach more than a few weeks of the lazy, tropical life.

Marietta always believed psychoanalysis saved her. For five years, she went every day. She developed the cool, disaffected style of the professionally analyzed; later in life she appeared to behave as if her years of therapy had freed her from feeling any restrictions from her family. Marietta and Ronald began to lead separate lives. They spent much of their time apart, although they remained loyal and close companions. "I know that at times I've not been easy—leaving my beloved Ditchley & starting life again here caused me much pain which in turn I must have communicated on to you," he wrote her, adding, "You have given me Penelope & words cannot express the wonder of that."

Ronald Tree became a colonial power in Barbados, where he developed a large resort called Sandy Lane. Marietta threw herself into reform politics in New York and worked as a drone at the Lexington Democratic Club, often taking Frankie with her. It was then considered a noble calling to fight the clubhouse politics of New York, where machine bosses such as Carmine DeSapio, in his silk suit and dark glasses, delivered the votes to the county leaders.

In the Trees' fabulous house on East Seventy-ninth Street, Marietta began to entertain her old friends from the war as well as everyone she met in New York politics. In the dining room at "Little Ditchley," as the house quickly came to be called, Lillian Heilman might go at it with Bill Paley over Stalin, or Arthur Schlesinger, down from Harvard with his then wife, Marian, would decry McCarthyism and Cold War Republican politics. Ronnie was absent from many of these dinners; his dislike of the smart, brittle talk of the New York intelligentsia drove him to spend much of the year in Barbados. In retrospect, the era was golden, and the dinner conversation was naive and xenophobic. Marietta's friends argued over reforms, but they were unable to see the larger picture, to imagine that the ramifications of the Kennedys' machinations to obtain power were possibly dangerous for the country, that Manhattan could unravel without the domination of the party bosses, or that an incomprehensible wild man like Barry Goldwater might just reflect the new populist mood in the country, for theirs was a tight group that confirmed one another's opinions.

In the winters, the Trees would return to Barbados, where they used Heron Bay as a retreat for their circle of friends. Kitty and Moss Hart came every winter, as did Barry and Mary Bingham from Louisville, and Evangeline and David Bruce. Claudette Colbert was down the beach, as were Ingrid Bergman and her husband, Lars Schmidt. On Christmas Day, Marietta would present each member of her house party with a small red engagement book from Smythson's, embossed with their initials in gold. Her presents were beautifully wrapped by Penelope's nanny, Mabel, in shiny pink-and-green paper with elaborate bows. The house staff wore crimson-and-gold sashes over their uniforms. Marietta often invited local black politicians to lunch, and she and Ronnie brought an ambitious literacy program to the island and started a "meals on wheels" food-delivery service for the elderly and infirm.

Once, Marietta had fought the Establishment; now she was at the center of it. By the Kennedy years, she was written about frequently in the rotogravures. She posed for the Times in front of her coromandel screen, or swathed in fur on her way to the United Nations. The U.N. job catapulted her into national fame—"Our Top Girl at the UN," Look magazine called her. Her recipe for loin of pork appeared in the columns, as did her views on international life. "She still blushes when the Russians anger her," one writer wrote in Look.

For years, those closest to her have speculated about Marietta's long relationship with Adlai Stevenson. Stevenson was Marietta's "calling card," a friend said. He called her Zuleika Dobson, after Max Beerbohm's bold English heroine, and became her mentor. When he lobbied for her U.N. appointment, Marietta wrote him, "My gratitude to you flows like Victoria's cataract for appointing me to the U.S. Del—for I realize now that all my life has been in preparation and in hope for the last two weeks. I only hope that the results [are] as constructive as the soaring fulfillment." The intellectuals of the "silent generation" revered Stevenson and jockeyed for his attention. A circle of rich, accomplished women fought over him, including newspaper heiress Alicia Patterson, Ruth Field, and Jane Dick of Chicago, but his sons have always believed that the woman he intended to marry was Marietta Tree.

Marietta first met Stevenson in 1946, through Ronnie Tree. In those days he was a rather whimsical idealist whose desire to be Illinois governor seemed a fantasy. Marietta contributed to his first campaign and wrote him from Ditchley when he swept into the statehouse in 1949. "No one can believe the vote! All congratulations!"

Back in New York, she was determined to be at the 1952 convention and got a menial job on the state committee so that she could be part of the crowd. In Chicago, she was sharply observant. Adlai, she later told one historian, looked "like a pyramid" addressing the crowd. "I was irritated by his views on civil rights and Arab-Israel affairs—they were not my views," she said. "Marietta was always trying to move Adlai to the left—those conversations I can remember," Frances FitzGerald told me. Stevenson respected her nerve and listened to her as much as he did to the cynical Alicia Patterson. "[Alicia] scorned my liberal views," Marietta said. Marietta was not afraid to be tactless to get her point across. She told Stevenson's biographer John Bartlow Martin that she sensed Adlai was "antiSemitic," and that that infuriated her. "Why do you always have to say a 'Jewish banker'? " she would scold him.

Within Marietta's circle, the relationship was commonly discussed. She worked doggedly in the 1956 campaign as the New York head of the Volunteers for Stevenson and traveled with him and Alicia Patterson around the world. At campaign headquarters in New York, Marietta often walked around in her stocking feet. More and more, Stevenson drew closer to Marietta. Once, in the late 1950s, he was staying in a Lake Como villa. Alicia was his guest. Hearing that Marietta was set to arrive on her departure, she refused to leave. "It was a nightmare," said a man who was Stevenson's aide at the time. "Alicia was in a rage that Marietta was coming. I had to walk her around the lake until she finally agreed to get on the train."

She sensed Adlai was anti-Semitic. "Why do you always have to say a 'Jewish banker'?" she would scold him.

What was their relationship? At the Seeley G. Mudd Library of Princeton University there are dozens of letters and notes from several unpublished interviews with Marietta Tree that suggest a true intimacy. Marietta told John Bartlow Martin that Stevenson spoke constantly to her of his mother. "He told me she was massaged on her bed and he used to watch her, and he was very interested [in this], especially her bosoms. ... She turned him into an aural man. Through all that reading aloud. You know he couldn't learn anything by reading—he had to listen. ' ' He talked to Marietta about his first encounter with a prostitute: "It horrified him."

Her later letters to Stevenson were quite intimate. By then they had developed pet names for themselves: he sometimes playfully referred to her as "that lump," and they called each other Mr. and Mrs. Johnson. Once, in her U.N. days, she wrote him from London, where she was on a trip with Ronnie.

A., Have been here a week, and it seems eight. We have been feted, entertained, wined, dined, balled, teaed, theatered etc. by the warmest friends.... Why can't I enjoy all this? Real answer. Because am far away from Johnsonville. ... I pray [your trip to Los Angeles] not too exhausting and overladen with pate de foie gras. Heedst the five pound promise.

I know a bank where the wild thyme grows and keep enclosing myself in the dream of it. M.

"I always assumed that Adlai Stevenson was in love with my mother," Frances FitzGerald said. "The fact that she wasn't going to do anything about it made it all the more interesting." She had long ago made the decision never to leave Ronnie, for they appeared quite content leading separate lives. Once, at a dance at Brooke Astor's, Adlai and Marietta danced the whole night, and "his hand was way below her waist," a friend said. "It was clear that he was crazy about her." "She hated the whole subject of sex," FitzGerald told me, although she had a clear memory of traveling in Spain with her mother and Adlai. "Our rooms were quite close together, and I had the feeling that Adlai was roaming around." Stevenson stayed at the Waldorf Towers in New York, and Marietta confessed to Susan Mary Alsop that when he was in town she came home at "four in the morning." Friends learned never to ask Marietta certain questions, for she was not beyond telling lies to protect her private life. "Marietta, did you go to bed with John Huston?" the publishing executive Parker Ladd once demanded. "No!" she said, then swiftly changed the subject.

She always camouflaged her morbid fear of death, perhaps because of the terrible effect Adlai Stevenson's heart attack had on her. "When they got Adlai to the hospital, Marietta was standing up at the top of the stairs absolutely sobbing as if her heart would break," Mary Warburg said. Susan Mary Alsop flew back to Europe with her from the funeral. "She just reminisced about him.... It was quite apparent how much she loved him. When we got to Paris, I was desperately worried that she might jump into the Seine, and I called her at the crack of dawn every day." Grieving terribly, Marietta left to join Ronnie in Florence at a villa they had rented. She remained in bed for much of that month, but Ronnie didn't comment. "His courtesy and his good manners never deserted him," Susan Mary Alsop said.

She became even more determined that nothing would throw her off course. When Ronald Tree died in 1976, he left her only her two houses, which, despite a real-estate slump, she immediately sold. The mansion on Seventy-ninth Street, now a consulate, brought her only about half a million dollars. She was desperate with grief. Once, staying at Mary Warburg's, she opened a top drawer in the guest room to find some of Ronnie's shirts that he had left there. She began sobbing "uncontrollably," Mary Warburg remembered. She set about reorganizing her life. "I made a list of what to do," she told a friend, "and I realized I had every qualification to go on corporate boards." She went back to college and studied accounting to prepare herself.

Marietta Tree lived to see Manhattan fill with crack addicts and the homeless, but she remained without cynicism, so optimistic that she became active in the Citizens Committee for New York City to try to alleviate the new misery. She "spent thousands of hours and she raised millions of dollars for us," Michael Clark, the director of the Citizens Committee, told me. Each year she would write "four to five hundred personal letters" to raise money for youth programs, drug-counseling services, and block associations, but ironically she gave very little money herself. "A cousin of Marietta's told me that the P in Peabody stands for parsimonious," Clark said.

Once, Frankie and Marietta were out walking during a garbage strike. "As we were stepping through tons of trash on Fifty-seventh Street, my mother kept saying, 'Isn't New York wonderful? I can't think of anywhere else in the world I would rather live!' "

" What would you have liked to ask your mother that you never got to?" I asked Frances FitzGerald.

"I wish I truly could understand how my mother moved away from her family and became what she became," she said.

We were sitting in Northeast Harbor in the small cottage on the water that FitzGerald shares with her husband, the writer James Sterba. FitzGerald has her mother's posture and perfect elocution, but she measures her words carefully. She writes examinations of American culture and politics and lectures on foreign policy. She won a Pulitzer Prize for her study of the Vietnam War, Fire in the Lake. She waited until she was fifty to marry.

Frances and Penelope have always called their mother Marietta, as if they understood from an early age that she was not maternal. If they wanted her attention, they had to enter her world. The same isolation that Marietta experienced in her childhood with her mother, she unwittingly repeated with her daughters. In later life, when she saw in herself certain traits of her mother's, Marietta would "go bananas," FitzGerald said, but she could never transcend her emotional legacy with her children. Like her mother, Marietta didn't "analyze personal relationships. She pushed away a lot of things," FitzGerald said.

As a mother and a wife, Marietta was unfailingly correct, but as her own mother had been with her, she was, as Dorothy Hirshon said, "fairly detached." Frankie saw her mother as "a glamorous and incredible figure," but she never felt intimate enough with her to work her way through her closets or borrow any of her clothes. As a young woman, she was often wary of bringing boyfriends to Barbados, because her mother, perhaps unconsciously, would dazzle them. "I was often in a rage," she told me, but later she began to understand that her mother couldn't help pulling the focus in a crowd. "My mother had to have all the guys in the room," she said.

One year ago, FitzGerald and her new husband were visiting her mother on Sutton Place. Suddenly, Marietta dropped to the marble floor of the foyer and did "fifteen perfect push-ups," as if to demonstrate her physical superiority. Marietta, however, did include Frankie in many of her activities, taking her in the summers to Venice or with Adlai Stevenson to Africa, where she met Albert Schweitzer. "I got the sense from my mother that I could do something from the earliest age!" she said.

Frankie appeared to suffer less than her half-sister, Penelope, for she was uncommonly bright and her mother encouraged her accomplishments. When they came back from England, her I.Q. was tested for school. "I remember Marietta saying, 'Frankie is so brilliant! She has an I.Q. of 151! I know I am going to be taught by her. I feel so insecure!' " Sam Peabody said.

When FitzGerald was in her twenties, she left for Vietnam to write about the war. "My mother arrived on a tour for the State Department. I went to meet her in my jungle khakis, and she was all in white with this fabulous hat! Here was this vision! I remember being furious, but also very proud because she was so beautiful.... I went to join her somewhere in the jungle, and my plane had to make an emergency landing. I looked down from the plane, and I saw her doing laps in the South China Sea next to a destroyer. I was having anemic hallucinations, and she was being feted with tea dances. But when she saw the horrible condition I was in, she said, 'We are leaving.' She took me to Singapore and stayed with me in the hospital for weeks. She saved me then. I was able to get back to Vietnam, and then months later I returned to New York. When I arrived, there was Robert McNamara in the library! I had expected to be the conquering hero in my house, and there was the enemy being entertained." (Marietta's brother Sam had also observed her need to accommodate men in power. "It irritated the bejesus out of me that she would sit down with Henry Kissinger and see nothing wrong," Sam Peabody remarked.)

Penelope was a toddler when her mother attempted to regroup in New York. By then, Marietta, like her grandmother Parkman, appeared to have lost interest in child rearing. Penelope became a shy, fragile child who would often cling to the curtains when visitors came. She was, however, doted on by her father, who would spend hours with his daughter, appearing to find in Penelope the empathic companion he longed for in his wife. "Your mother says it is time to come out of the water," Tree used to tell Penelope, as if trying to drive a wedge between them. "Ronnie is so permissive with Penelope," Marietta would complain to her friends. "He lets her do anything!" On the night of Truman Capote's legendary Black and White Ball in 1966, Marietta and Ronnie encountered sixteen-year-old Penelope in the library, dressed in "ravishing but very scanty black leotards," Susan Mary Alsop recalled. Capote himself had invited Penelope to the ball; Betsey Johnson designed her outfit. The next morning, Penelope recalled later, Diana Vreeland called to tell her she should become a model. Within two years, much against her parents' wishes, Penelope left home and moved in with the English photographer David Bailey. Later she moved to Australia, where she now lives with a psychotherapist with whom she has a twoyear-old son.

For years Penelope appeared to believe, according to friends, that she had never really gotten a chance to know her mother. "My feelings are so complicated about her that I don't understand them," she told me. I asked her what she knew about her parents' early relationship. "I know they met at a party. That's really about all. My mother never talked to me about anything like that." When Penelope's daughter, Paloma, was bom, Marietta, according to a friend, "began to realize what she had missed not being close to her daughters." She attempted to make up for lost time, flying to Sydney frequently to see her grandchildren and calling weekly on the telephone.

Penelope and Frankie learned to come to terms with a basic fact: "Marietta was the least introspective person we had ever known," Frances FitzGerald told me. "Anything that might have hurt her, she just wiped out."

She had long kept her cancer a secret. Eight years ago, she asked her brother Sam to take her to the hospital, where she had a lump removed from her breast. "She never mentioned it again," he said. Marietta appeared to believe that she could will her recovery through the sheer force of her exuberance. She never slowed down until this year, when the cancer recurred. By the time the lump was visible on the mammogram, the cancer had spread. Marietta concocted an elaborate hoax for her brothers and friends. "I have antibiotic poisoning," she told even her closest friends Susan Mary Alsop and Kitty Hart. Only Frankie knew the truth, and she was uneasy about being the keeper of the secrets. Marietta increased her activities, attending every lunch and dinner she could. Winston Churchill had told her when she was a young woman, "Age is a somber period." She determined that for her it would not be so. In June she ran into Robert Caro at the Century Club. "I have decided to write my memoirs, and I want your help," she told him. "Call me in the fall!" She was wearing bright-red stockings, Caro remembered, and looked "stunning."

In Maine in late June, Sam Peabody walked into his sister's bedroom. She was in bed, staring into her hand as if, he said, "she were facing the end of her life for the very first time." For much of the month, she was too weak to get out of bed. "I don't know what is the matter with me," she kept saying. "I haven't been in bed since I had Penelope." She flew back to New York with her close friend Joe Armstrong, a publishing consultant involved in many New York charities. Armstrong held her hand the entire way. Fading then, she called her close friends and her brothers, saying, "Please come to see me! I do miss you so. Let's just be cozy."

One night in July, she went to dinner with Punch and Carol Sulzberger, the owners of The New York Times, and former Times executive Sydney Gruson and his wife, Marit. The Grusons and the Sulzbergers had been close to Marietta for more than thirty years. They were overcome with worry, for Marietta was wearing a black patch over her eye and complained of double vision. She had lost twenty pounds. The evening was fraught with portent, but the next day Marietta left a message on Sydney Gruson's answering machine: "That was simply the best and finest time I ever had in New York."

She wouldn't admit that she was dying, not to anyone, not to herself. Sitting in her doctor's office once with Frankie, she suddenly turned to her and said, "You know, I am not sure that I would have done this for my mother." "Don't be silly," Frankie said, then thought, My God, she is probably telling the truth. "I said to her, 'Well, you are a much better mother than your mother was to you.' And she said, 'I am afraid that isn't so. I would love to do it all over again.' "

In late July, Penelope arrived in New York for her annual visit. She was told then that her mother was gravely ill. To friends who would call, Marietta said, "It is so marvelous having Penelope and Frankie here with me. They are taking care of me so beautifully!"

Several days before she died, Marietta instructed her secretary to accept all invitations for the fall. She wrote to a friend in Australia, "I am thrilled you are going to be here before Thanksgiving and look forward to it greatly. ... At the moment I am laid up, but expect to be on my feet by Labor Day." She never gave in, even at the moment she died. "Get me out of here," she told Frankie. "She went down swiftly like a beautiful sloop hitting an iceberg," FitzGerald later wrote to Marietta's dear childhood friend Bill Blair.

Marietta's funeral was in Northeast Harbor at the tiny stone church where fifty years earlier she had married Desmond FitzGerald. Brooke Astor brought flowers from her own garden and arranged them "as if for a party." Frankie and Penelope taped Marietta's tiny scarlet leather 1991 appointment book from Smythson's to the top of the box containing her ashes as it went into the ground. The book was filled with appointments through Christmas. The last thing George Peabody remembered seeing of his sister was a bright flash of red.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now