Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHIGH-LIFE Crash

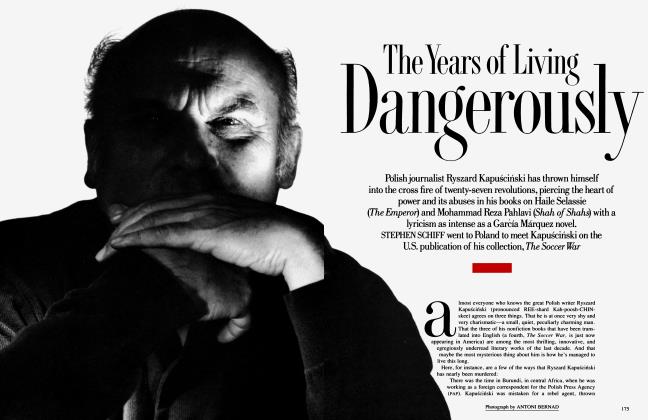

Like a jet-set Icarus, journalist Taki Theodoracopulos, the noted (and notorious) "High Life" chronicler, tempted a few too many Fates when he flew into Heathrow with twenty grams of coke— and landed in Pentonville, London's most gothically gruesome jail. In an excerpt from Nothing to Declare he recounts his harrowing odyssey

"We cant have a millionaire like you pissing in an old pot and giving Pentonville a bad name, can we now?"

It's impossible to be lonely in Southampton during the sparkling summer months, especially if you happen to own a spacious house with a swimming pool and tennis court, a cellarful of wine, and a courteous staff in attendance. Southampton, for the benefit of anyone who has spent the last fifty years in Albania, is the luminous little village on Long Island which serves as seaside refuge for New York's civilized rich during the unbearable heat of urban summer. As full of socialites as it is free of socialists, Southampton has been described by the glossy magazines that describe such places as an antiseptic, overrefined backwater of grand houses, wicker chairs, yellowand-white umbrellas, and long green lawns.

It is, of course, much more than that, the more being the people who live in the grand houses. For a few glorious months each year, they create a community which might be the nearest we'll get, in this forlorn age, to the countryhouse culture the English gave to the world and which once seemed the only way to live. No doubt this, too, will be extinguished by the unsparing barbarism of modem life. Southampton falls into the category of things governed by what I call, in the appropriate parlance, "The First Law of Sociodynamics." Any social tradition which depends for its survival on the absence of change will especially attract those who have made the greatest profit from change. And so with Southampton, where the Old Guard is increasingly under siege from the not-so-old Guard, the out-andout nouveau, and the funny-money people from both continents.

I go on about Southampton in this mildly obsessive way partly because it represents the last refuge of the ancient social regime whose morals and manners I always supported against the drug-and-celebrity circus replacing it— only to find that, one day, I, too, had become part of that circus. And, further, because the perfect tranquillity of Southampton now seems a little eerie, arousing superstitions in me which were supposed to have died out with my ancient-Greek ancestors: I've grown wary of nemeses in exalted places. For it was from this sanctuary of privilege that, within forty-eight hours in the summer of 1984, my life chose to take a sudden dive to the lowest of the lower depths. That is to say, one day I was playing tennis and cuddling my children in sunny surroundings; the next day I found myself under arrest on drug charges at London's Heathrow Airport.

July 23, 1984, a day I shall not soon forget, dawned bright and hot. Planning to fly to London that night, I spent several hours on the tennis court, getting nice and tired for the ride. About ten guests were visiting and we had a long softball game on the lawn. Then, after a late and very liquid lunch, my wife, Alexandra, and an English couple drove me to the airport. Alexandra was to meet me a week later. From London, we would fly to Italy to stay with friends; from there, on to Greece and my boat.

But I had left my passport in my Manhattan house. That meant I had to miss my flight and drive into the city instead to fetch it.

Leaving me with a free night.

So I headed for a disco.

I went to the barman, whom I vaguely knew, and asked if he had anything. "I've got the best there is," he answered, "but you've got to buy the whole thing or nothing at all." I was not surprised. People who sell drugs are hardly sensitive souls. But no one pushed me to buy. I fished out my wad and paid $1,800 for twenty grams of coke, stuffed it into my back pocket, and headed for the bathroom.

I still often wonder: had I taken any of it that night, would matters have turned out differently? But I didn't. The bathroom was a scene out of Dante, so I fled the whole place and went home to sleep. In the morning, I went for a run, did some ⅛ karate with my sensei, got my papers together, and caught an early flight ⅝ to London, congratulating myself on not having gotten wrecked the night before.

The flight was perfect. I had a sound sleep and, upon arrival, was the first one out of the plane and through passport control, with no luggage except a small carry-on. The rest of my clothes were in my London flat. Passing through customs, I was asked if I had anything to declare. I said I had nothing. The officer looked through my small bag and waved me on. Then, as I was leaving, I heard a voice say, "You're going to lose that envelope."

Being Taki, I replied, "Oh, thank you. If only you knew what was in it."

The man crooked his finger. "Come back here," he said.

And that was it.

The first thought that crossed my mind as I entered the holding cell was that life would never again be the same. The word "never" has a permanence I've always found hard to digest. Yet I remember distinctly that on this occasion I had absolutely no doubt that some terrible dark shadow had caught up with me for good. I had now become one among many whose money and privileges had led them from self-indulgence to self-destructiveness to criminal misconduct.

The cell was located somewhere in the bowels of Heathrow Airport. As I waited for a body search, another thought flashed over me: the morbid fascination with danger I had always felt was over. After a complete search, the officers read me my rights and the grilling began in earnest. It went on for ten hours. While it was still continuing, two agents drove into London and took apart my flat. They found nothing, and upon their return, the atmosphere relaxed, the questioning became softer, less hostile. In fact, I was even offered a cup of tea. A while later, we packed it up and headed for a police station. Once there I was booked, fingerprinted, and locked up for the night in a windowless cell.

As everything had been taken away from me, I could tell time only by the activity I could hear outside. Finally, the door was banged open and someone told me to follow an officer. We drove in a Black Maria for about half an hour and then, once again, I was put into a tiny cell and instructed to wait. About three hours later, an officer stopped by and asked me if I had a lawyer. I said no, and was assigned one by the court. Eventually he came in and I told him everything. I also asked him to make sure that no newspapers got hold of the story. He seemed like a nice man who knew his way around, and my spirits rose. But when I was ushered into a courtroom above the cells, my heart sank. The whole press gallery was full, and I could see some familiar faces among them.

I pleaded guilty to the charge of importing twenty grams of cocaine. Then the officer who had busted me took over. He said that he was convinced I had been carrying the stuff for my personal use, that I had been cooperative and truthful, and for good measure he told the court how I had pretty much given myself away by volunteering the contents in the envelope even before any question of a search arose.

From the comer of my eye, I noticed a couple of hacks sniggering. My lawyer got up, and in two seconds flat I knew my destination was definitely going to be indoors. Although I had instructed him not to mention that I was a writer—I was then and am still a columnist for The Spectator—the presence of a small company of Fleet Street hacks made my request superfluous. So he banged on about what an important journalist I was, how the pressure of my work had driven me to cocaine, and, for good measure, he threw in that I was almost as rich as the Queen herself. He went on to add, "In the group he runs around with, cocaine is considered a lesser evil than a good glass of red wine." After that remark, of course, there was loud sniggering from the press section. But the kind old boy and two ladies who made up the troika of magistrates neither approved nor were amused. I raised my hand and asked to be recognized; I was given a minute to confer with my lawyer. "He now tells me that cocaine is not as widely used as wine in his circle" was the way my counselor put it when we resumed. More sniggering and a warning from the bench followed that pearl of wisdom. Finally the three magistrates retired, and I sat waiting while every pair of eyes in the room took in my unkempt appearance, which became more unkempt by the minute as I began to sweat profusely.

When they returned, the old boy said, "The importing of cocaine into Britain is a serious offense. Although the defendant is of previous good character, and the court is convinced the cocaine was meant for his personal use, I nevertheless sentence you to four months in prison."

I was then taken back into the cells, where my attorney appealed and I posted bail pending that appeal. By midafternoon I was free, and I drove into London, five pounds thinner and £5,000 poorer. The English summer was just beginning, but to me it felt like the last days of autumn—gloomy, depressing, and fraught with a sense of foreboding.

Too embarrassed to return to the old life, I fled to the country, to deepest Wiltshire, and remained there for the duration. I took a different lawyer and volunteered to have spot drug tests made in order to show, when my appeal came up, that I was being a good boy and a reformed character. My wife and children came over, but the climate between us was icy. Alexandra simply could not stomach the fact that I had done what I had. She thought, and rightly so, that I had compromised the future of my children, something that made me feel even worse than I already did. My appeal was scheduled for December 14. I tried to envision what prison would be like, but I still couldn't believe that I would actually end up there, serving time. All my life I had gone to the brink, yet somehow escaped disaster. It's unwise to become too dependent on the last-minute intercessions of Lady Luck.

Two days before my appeal, The Spectator gave a dinner for me. The next evening, there was yet another good-bye party, given by John Aspinall, England's greatest gambler and poshest party giver, in his club, the Aspinall Curzon. Married to Sally Curzon, Aspinall is an English swell, a sort of Elizabethan aristocrat. Fearless, indomitable, and deeply civilized, he loves to be surrounded by fierce, wild animals and people of spirit. On the night of the party in my honor, he filled his fabled club with my poshest friends, and there were speeches galore. The English aristocracy loves nothing more than to get up and crack jokes about the imminent demise of one of their friends. I got drunk and later, at Annabel's, suddenly realized that I was acting silly. Alexandra, too, was upset at the circuslike atmosphere gripping my friends and me. I said my good-byes quickly and took her home.

Unable to sleep, I wrote my last column, shaved, showered, and had a barber come at seven in the morning to give me an old-fashioned crew cut. At eight, a driver took me to south London, to Southwark Crown Court, where my appeal would be heard. Meantime, the children were sent off to America with the explanation that their father was about to leave for Australia—as indeed he would have had to a century ago—to do research for a book about prisons. As they left, I felt suddenly afraid that I might break down. But I didn't; I held up and, to my surprise, found myself telling jokes, even managing to make them shriek with laughter, the way children sometimes do. Separating from them, I wondered what other men go through, how they behave with their families in the last moments before departing for a long prison sentence.

For someone who has always been an unshrinking supporter of law and order, I was already wavering on the question of prison and its benefits. The car sped through the still, inanimate streets, and, with London rolling by, I noticed that for the first time in my life I had taken no money with me. I felt a strange satisfaction. The relentlessly privileged life was about to end and a great curiosity, mine, was beginning.

As I walked into court, a light rain had begun to fall.

Finally, the day of judgment. Judge Trapnell, resplendent in wig and gown, is flanked by two lady magistrates. A bad sign, I think to myself. During my first trial, both ladies insisted on a custodial sentence, whereas their male counterpart did not. He revealed this to my brilliant lawyer immediately following my trial, in a nearby pub.

The first case is that of a large black man, pleasant-looking, who was caught trying to smuggle five kilos of hash into the United Kingdom. He is from Ghana. Trapnell throws the book at him. Then it's my turn. My Karamazov-size hangover evaporates as I step up to the dock. While various clerks shuffle papers and confer with barristers, I keep my eyes lowered. I couldn't raise them to save my life. I feel so embarrassed. Sitting in the dock awaiting a sentence as a common criminal, accused of a nonpolitical crime at that, will unman the stoutest heart.

The press section resembles a Japanese subway train during rush hour. The prosecution reads out the charges in one minute flat. It does not ask for a custodial sentence, Then John Mathew, Queen's Counsel, begins to plead for the defense. Q.C.'s are called "silks" because of the silk robes they are required to wear. Well, John Mathew's language today matches his robe; in fact, he lays it on so thick that for a moment I fear the judge may praise me rather than condemn me. Mathew speaks for about one hour, which, I am told afterward, is a good sign. Usually, judges ask the defense to get on with it, but on this occasion Trapnell behaves attentively, even nodding his head a couple of times. Mathew argues that here is a man of considerable wealth who could have chosen to live an indulgent life, but had instead become a war correspondent, etc. He points out that throughout the late sixties and seventies, and in places like Vietnam and Cambodia, I had never taken drugs, having succumbed to them only lately, owing to my work covering nightclubs in London and New York. Mathew sums up by asserting that prison is the last place to send an overworked and sensitive man like myself, that I have already been punished enough, since I am now professionally destroyed.

Judge Trapnell nods—understandingly, it seems to me—and my spirits soar. The three then rise to ponder my fate.

Ten minutes later comes the familiar knock, the bailiff's "Everybody rise," and the judges return. Trapnell fixes me with a look and utters only a few brief words, "We feel bound to dismiss the appeal." Immediately, I am seized by the elbow and led out of the courtroom through a small door next to the dock. As I go, I turn and look at Alexandra. She seems confused, not having yet realized that those words mean I am to be a guest of Her Majesty's in prison for the next four months. I have time only to wink at her and give her a smile.

Southwark's holding cells, as they are called, are small and clean, but windo wless and oppressive. Knowing that for the next four months I will be deprived of that most precious of privileges, freedom, does not help matters. The horror of incarceration dawns on me immediately, a combination of claustrophobia and deep depression. It is hard to describe the feeling. I try to compare my plight with that of American pilots who were kept in cages by the North Vietnamese for years, but that doesn't help. The pilots had landed there after answering their country's call, while I have landed myself in this shit simply through self-indulgence and arrogance.

(Continued on page 198)

With the first whiff of freedom came and attack of paranoia.

(Continued from page 190)

Self-pity and disgust rule the day.

At six on the dot, my door is opened and I am handcuffed to the large black man from Ghana. He smiles sheepishly at my obvious discomfort. Then, along with a half-dozen others, we are led into a bus headed for Pentonville, the Dickensian jail that will be my home for the next few months.

Pentonville is one of the filthiest and oldest prisons in England. Built when Queen Victoria was still wetting her knickers, it has remained unchanged ever since. As we drove through the massive steel door, I took one last look at the outside world. It was dark and depressing. The rain came pouring down.

Few places inspire so many myths and misconceptions as prison. Unlike the scenario in Hollywood movies, inmates do not come up to a newcomer and introduce themselves. Those who have done time before know how to get around the waiting and get processed early. They also know what jobs to go for and what to say to the screws, or guards. That day, most of the people waiting to be processed were recidivists, and a surly lot. I was fingerprinted, then taken into a room where I surrendered everything in my possession except my watch and a small radio with one frequency. After a cold shower, I was issued two pairs of blue jeans, two whiteand-blue striped cotton shirts, two pairs of gray socks, one sweater, one denim Eisenhower jacket, one toothbrush, a small mirror, one pair of black plastic shoes, one towel, two blankets, two sheets, and one pillowcase. The blankets were soiled and dirty, but the clothes, although old and falling apart, were reasonably clean.

Stripped and washed, ritually divested of my outer self, I was uniformed and processed into becoming an inmate like any other. Now there was nothing left to do but to start serving time. I had yet to exchange a word with an inmate; no one had paid me the slightest attention. When my name was called out, I passed through a large steel door and into a cellblock.

Pentonville, with its four long, high, and narrow cellblocks, looks like the fingers of a hand. At its palm, so to speak, is a central area with a glass enclosure from which officers bark out commands through a loudspeaker. Each outstretched block has four landings, long galleries with iron railings giving access to innumerable steel doors. The landings are connected by catwalks. Wire nets enclose each landing to prevent people from being thrown down. My cell, No. D-31, was mind-numbingly small: nine by thirteen feet, and seven feet high. Some cells sleep as many as four prisoners, but to my relief only one man was waiting when I entered.

The cell held two steel beds, two wooden desks with two chairs, and, in the corner, two chamber pots and two plastic pitchers for water. My cellmate looked less than overjoyed to see me. He grunted something that sounded more digestive than verbal. I assumed that it was a prison custom to play as tough as possible upon meeting a new man, so I made no effort whatsoever to break the ice. After a while he went to sleep, still without saying anything. I got partially undressed, made my bed, and got in. I tried to close off my mind and go to sleep. Needless to say, it was impossible. I could detect other men's smells on my blanket. I could hear people talking through their windows— mostly obscenities with racial overtones, all in harsh, bragging sounds. Near the ceiling was a window with thick bars stretched across it; I could see a little bit of black sky. I spent the night mournfully gazing out at the odd star that fastmoving clouds allowed me occasionally to glimpse.

DECEMBER 15, 1984

It is 6:45 A.M., and the realization comes—Oh, God, I really am in prison. I hear warders banging on the steel doors with their heavy keys and jiggling the judas holes as they inspect waking men inside their cells. Yesterday I was warned that if I didn't get up and about in a jiffy the door would remain locked at breakfast time. A loud racket erupts just as I arise. Inmates are screaming obscenities, or singing, or banging on the walls with plastic cups. I have fifteen minutes to make my bed, wash and shave, and get dressed before being allowed out for what seems the most gruesome part of the prison day: slop-out!

As I soon discover, on each landing there are two urinals, which serve more than one hundred men. There are no toilet facilities inside the cells. One uses the chamber pots, which are "slopped out'' each morning. Next to the urinals are two large basins with a faucet over each, and that is where one brushes his teeth, cleans his potty, and refills his bucket with water.

Brushing my teeth is a punishing experience. As the basins are located next to the urinals, I have to brush while others slop out, which for all the world is like dining in a public toilet during a diarrhea epidemic. First I wonder whether I can go for four months without brushing my teeth. Then I wonder whether human nature, mine too, will prove so adaptable that I will one day become immune to others' slopping out while I brush.

After that vile initiation into prison hygiene, I am locked up once again while men from various wings and landings go down to get the first meal of the day. Pentonville has no central dining area; all meals are taken in one's cell. Like most people unfamiliar with prison, except for Hollywood's version, I thought that during mealtime I would sit with whomever I wished in a vast dining room, exchanging "tough guy'' talk with men like James Cagney or George Raft. But, again, reality turns out differently. My cell is unlocked and, as directed, I go down the narrow iron stairs to the bottom landing, where there's a soup kitchen. Talking is prohibited, as is keeping one's hands in one's pockets. I take with me one plastic knife-fork-and-spoon set, plus one plastic bowl and plastic cup.

The breakfast menu consists of four slices of white bread, one piece of margarine, a helping of porridge, and a cup of tea. Walking to and from breakfast, for some reason, the old-timers make the most vivid impression on me. They are extremely pale, but they swagger around with the assurance of old boys in prep school.

On my way back to my cell, an old man comes up to me and slips me a brand-new chamber pot. "Here, this will do for a prince like you," he says, smiling and showing very few teeth. John, my cellmate, tells me that this is Sid, the orderly of our landing, a professional thief who has spent most of his life in prison. Sid likes it inside, according to John. He feels the screws and the inmates are the only family he has. This is the first act of kindness I've received in what already seems like a year, and it occurs to me that, ironically, in terrible situations such as prison, it might well be precisely those acts that are hardest to handle.

Around eight A.M. we are unlocked again, this time to begin work. I thank Sid as he comes around counting the trays. "We can't have a millionaire like you pissing in an old pot and giving Pentonville a bad name, can we now?" he replies. He has read in the papers about my imminent arrival; he is thrilled to meet a rich man face-to-face. I am thrilled to meet a kindly soul inside.

It's up to Sid to hand out the few utensils allowed in prison—knives, forks, cups, and a safety razor once a week. No soap, however, or toothpaste. They have to be bought with one's earnings, which never exceed the equivalent of four American dollars a week, according to my cellmate.

Mr. Wrigley, the superior officer who interviews me about a job, turns out to be a nice man. I list my previous jobs on the outside, as well as the education I've had. He looks up at me and shakes his head. Then he asks me what my crime is. When I answer, he shakes his head some more and tells me I'm a fool. "You're also an embarrassment," he says. I suggest he assign me to the library. "Do you like girls?" he asks. "Then stay away from there. " He tells me to go back to my cell while he tries to find me something to do. And, as I leave, to my surprise he winks at me.

The rest of the day goes extremely slowly. Nothing happens. I sit in my cell and count the hours. But I'm starting to feel better. Even faintly optimistic. As far as I can tell, the worst enemy will be the suffocating routine, the monotony. The daily prison schedule goes something like this:

6:30 A.M.: First bell.

7:00 A.M.: Slop out, shave, and dress.

7:30 A.M.: Breakfast.

8:00 A.M.: Workshops.

11:00 A.M. to 11:45 A.M.: Exercise in the yard, then back to work.

1:00 P.M.: "Dinner."

1:00 P.M. to 2:00 P.M.: Lockup.

2:00 P.M.: Workshops.

4:00 P.M.: "Tea" and then lockup for the rest of the day.

John tells me about the different jobs: laundry, uniform stitching, accounting (prison wages), library, and gym orderly—according to my cellmate, the best job in the whole prison. I find myself believing in Mr. Wrigley, believing that he'll come up with the best job of all.

DECEMBER 16, 1984

I have already spent most of the night awake, my optimistic mood ebbing as I realize that the second day in prison is worse than the first. The natural curiosity one has about penal institutions departs as soon as the doors slam shut and the routine is established, which happens almost immediately. You wake up, you slop out, you go to work, you have dinner, you go to work, you have tea, you slop out, you go to bed. That's it. You don't look forward to the food or to the work or to the company. All I do look forward to, with the desperation of a dog pining for a bone, is the newspapers and books I hope will be delivered on Monday. English prisons allow inmates to receive newspapers so long as they have been arranged and paid for beforehand. I was so anxious about that that I left nothing to chance. Two weeks before my trial, I went around to the prisons in the London area and prepaid the newsagents in the respective locales to deliver the four English dailies and the International Herald Tribune to each of them. I trust someone is enjoying them in Brixton, Wormwood Scrubs, and Reading Gaol.

John spends all his time lying in bed looking at the ceiling. Occasionally he rolls some tobacco. He reads nothing and gives the impression he's happy he doesn't. Today we each received our one sheet of paper and one envelope, as we shall every Sunday.

For the first time in my life, I am truly able to understand what it is to be grateful for small mercies. This morning we had cornflakes for breakfast. We also had an egg, which I gave to Sid, who immediately gave me some soap in return. So finally I am able to wash my hands with something more than water, as I haven't since leaving home. On Sundays (and on holidays, Sid tells me), we have an extended exercise period in the yard. I looked forward to exercise, for all the obvious reasons, of course, but also because in Hollywood movies this is where it all happens. Once more, though, the reality left me bitterly disappointed. The yard has turned out to be just a small space between two wings, a space about the size of a small backyard tennis court. In it the prisoners walk hopelessly round and round in a clockwise direction.

The Rastafarians, and there are plenty in Pentonville, just stand about in front of the toilets, smoking, looking sullen and threatening. The rest walk at a doleful pace. I try to walk as fast as I can, covering approximately two to three miles in forty-five minutes, by my reckoning. But it is unpleasant work, dodging gangs of men who block the narrow path, spit nonstop, and hoot at me scathingly for trying to get some benefit from the exercise period.

I notice four men in the yard with large stripes of bright-yellow cloth strapped onto their uniforms. This means they tried to escape. They are not allowed to mix with the rest of us, except in the yard. One of the four looks very worn, as if he has given up altogether. Another has a disturbed, scrambled expression on his face—the look of someone just after a major car crash. He belongs in an asylum for the insane, poor fellow, certainly not among criminals, some of whom are making fun of him. The other two look as normal as the rest of us: angry, glum, and caged-up.

After dinner, served on Sunday at noon or earlier, once again we are locked up for the duration. I wonder whether to write a letter to Alexandra, telling her I'm all right, or to use the paper for my diary. Paper and keeping a diary were forbidden me in prison. So far I've been writing in between the lines of a bricklike paperback book, the only book I was permitted to bring.

DECEMBER 17, 1984

On my way to breakfast, a man yells down to me in Greek from another landing, calling me by my name and making a sign that we should speak later, just as the screws grab him and tell him to shut up. Then, while I'm walking in the yard, he approaches and introduces himself as Pavlo. He is a Greek Cypriot, doing six years for drug dealing. He seems an awfully nice fellow, giving me endless advice on how to beat the system. Most of it, alas, has to do with how to smuggle in drugs. "You have your wife or girl," he says, "put the stuff inside her mouth, and then when she comes in to see you, she kisses you for a long time. Then you slip it inside your bottom, as it's the only place the screws are not allowed to look." Pavlo is obviously high while he's telling me all this. "The day goes fast when you're high," he says. He shows me a picture of his wife and the daughter he's never seen outside the prison visiting room. Abruptly I stop feeling sorry for myself and feel sorry for him.

As I was warned might happen, the exercise period is cut short when it begins to rain. Once locked up, however, I find the first pleasant surprise to come my way. Four beautiful newspapers await on my bed, along with a letter from Alexandra. Just as I embark on the first newspaper, the door is unlocked and I am told to report to the gym immediately. The guard escorts me down the landing, past the "Rule 43" cells ("Rule 43" means that one is not to come into contact with the rest of the prison population—the group in these cells comprises mainly child molesters and stool pigeons, or "grasses," in English slang), and on to the gym.

The gym, it appears, is basically a basketball court with a few trilmmings—a punching bag, some parallel bars, a badminton net, and an old-fashioned weightlifting machine. At the end there's a small office where the instructors have tea. Mr. Leggett is the superior officer in charge, which means he wears a white shirt rather than a blue one, and sports two stars on his epaulets. He tells me he's been a prison officer all his adult life. He is a short but muscular man, avuncular-looking, and he turns out to be very kind. It just so happens that the previous gym orderly is being released from prison, and Mr. Leggett has called Mr. Wrigley to ask if there's anyone reliable for the job, truly— as John, my cellmate, mentioned—the best and most sought-after in the slammer. It means one can shower every day, change clothes twice a week, and avoid the steaming laundry and the bag-stitching assembly line. Above all, it's an end to those extra hours stuck inside the cell.

After a brief interview, Mr. Leggett informs me that the job is mine, with one small condition—"if you can make a good cup of tea." I tell him I'm a quick learner.

I'm supposed to hand out sneakers, T-shirts, and shorts to those who have not become too cynical to stay in shape. Then there's a certain amount of sweeping up and putting away of things once each hour is up. Then I repeat the procedure when the next group comes in. My first day in the gym goes rather smoothly. After I clean up, I'm allowed to walk back to my cell unaccompanied, the rest of the inmates having already been locked up fifteen minutes before me. This gives one a sense of superiority; it offers a rare opportunity to feel a bit different from the rest.

An odd thing happens after the evening exercise period: I am approached by a con who tells me he has just swallowed seven morphine tablets, and asks if I want one. I thank him but decline, as I think I've learned my lesson in that regard. Sid offers me two razor blades because, he says, I'm about to be moved to another cell for reasons unknown. I don't know what this means or whether I should be worried.

After slop-out the following morning Mr. Wrigley comes into my cell and says that I am moving. He offers no explanation. My new cellmate in Cell D-16, I discover, is the same man who tried to pass me some morphine yesterday.

I smell trouble.

"Tony the Loon" he calls himself. He tells me he is doing nine years for a bank job and has about three years to go. He's short, blond, bearded, and muscular, with Gene Wilder-like eyes and a swaggering manner. According to him, he's been a criminal all his life. He sees me as an amateur, probably a fool, who got caught doing something that had no monetary reward and involved very little danger. Tony prides himself on being the best getaway driver in London. The only reason he got caught, he explains, was that he was too stoned while pulling a job and skidded off the road with the fuzz right behind him.

After breakfast he rolls the biggest joint I've ever seen and offers me a drag. I politely decline. Drugs accentuate one's mood, and I'm hardly in the kind of mood that needs intensifying. But Tony makes me nervous. If a screw should happen to barge in, we'll both end up on "the block," the punishment cells, where, I'm told, one stays naked without bed or other furniture or anything to read.

DECEMBER 20, 1984

Once again I sleep badly, if at all. Tony plays the radio all night, smokes joints nonstop, and pops pills. He becomes progressively louder and more incoherent and almost abusive as I keep refusing to join him in his morphine-induced utopia. (Earlier on, he told me that he gets his dope from his wife, who visits him daily because he's been serving time in the boondocks and is here only for the Christmas holidays. The rest of us are allowed one visit every thirty days.) Furthermore, now that I know how dope gets through, I have one more good reason to decline.

I ask Tony what he's been doing for sex the last six years. "Boys," he answers. "I'm no queer, mind you, but we have these male whores that we use." In return, he says, the whores get protection and tobacco, in that order.

DECEMBER 23, 1984

I've been moved to a single cell, which provides certain comforts of privacy, yet it makes the time drag ever so slowly. With a stranger, one lies awake, aware of every noise, every move, hoping that one's vigilance will pay dividends. Fear and anxiety are antidotes to boredom. But, God, how slowly time passes once the door is banged shut and one is alone. The period from five in the evening until sleep comes, sometime around midnight, is the worst. Today I begin to walk diagonally across the seven-footby-thirteen-foot cell, daydreaming and longing to exhaust myself, but to no avail. Sleep is the most cherished commodity in prison.

This morning I gave all my tobacco to the wing cleaner of C-5 in return for a small bar of soap and some paper hankies, which he promised to provide after dinner. But when I looked into his cell, his things were gone and I realized that I'd been had. On his last day, he lied in order to get my smokes, knowing that he had seven hours to go and I have almost four months. I made it a point never to trust anyone again. He seemed like a decent chap, even going to the trouble to ask me what soap I liked.

The Christmas carols I hear over my tiny transistor make me gloomier than usual. Memories of happy times come flooding in, and I am sad, despairing. The weather helps, however. There is no snow to remind me of Gstaad and Christmases past. There's only rain and more rain, and gray ness.

DECEMBER 24, 1984

The prison is emptying out as screws are leaving for home, and being filled to the brim by what the English refer to as "dossers." These are bums, mostly elderly winos, who have nowhere to live. For Christmas, these unfortunate souls throw a rock through a large department-store window or assault a policeman in order to get themselves arrested, thus ensuring three square meals a day during the hols. Everyone in prison lives in fear of having a dosser put in with him; they smell to high heaven, and although one's sense of smell is deadened after a couple of days' living with the urine, the dossers have been known to make even old-timers throw up. Harry, who occupies the cell next to mine, tells me that two years ago he had one die on him, and as he had just been locked up for the night, he had to wait almost twelve hours before he was unlocked and the body taken out.

That is all I need for Christmas,.I tell myself, and then discover that Landing No. 4 of C Wing has broken pipes, so our solitary toilet will have to accommodate an extra seventy-five men this morning.

After breakfast I'm told to report to the canteen to collect my week's wages. The canteen, like the library, is nothing more than two connecting cells with the middle wall missing. I have earned the princely sum of £2, or $3.40. The screw who doles out the money tells me that mine is the highest salary in the whole nick, a fact I find extremely ironic, as I have never in my life been able to outeam anyone, least of all two thousand crooks.

DECEMBER 25, 1984

Breakfast today is a feast. Tea with toast, plus cornflakes and one egg. Later, after slop-out, we all receive our presents from the governor of the jail: one packet of butter, a bag of sugar, and a cake.

Mr. Leggett, from the gym, and another officer bring me three mince pies and a bottle of lime juice, which I devour almost immediately. They also bring me a Christmas card and a forbidden pack of ciggies. After a dinner of turkey and more goodies, the Salvation Army singers are heard caroling away. But they are soon drowned out by inmates yelling "Fuck off" in unison. Poor Salvation Army volunteers. I feel for them, but I also understand why everyone is outraged.. We all want the day to be over. And it's the longest one yet. I imagine my children and Alexandra asleep in America, or opening presents, and get more depressed.

DECEMBER 26, 1984

Suddenly, after breakfast, a screw I've never seen before comes into my cell and tells me I've got two minutes to pack my belongings. "You're moving," he barks. I try to tell him that there must be some mistake, but he smirks and gives me the choice of moving quietly or going to the punishment cells. My mind races. Am I being let out? Am I being transferred to an open prison, the British equivalent of what Americans call a country-club jail?

I gather all my meager belongings, including my two sheets, one pillowcase, two blankets, books, and clothes. I try to take my utensils with me, and my most loved object of all, the potty, but the screw, who is watching me like a hawk, orders me to leave those behind. He marches me out, down the landing and one stairway, and on to D Wing again, but not to my old landing, but to D-4, Cell 30.

To my utter horror, the cell is in a state of such filth that even the screw seems embarrassed. The two beds are both covered with excrement, the walls with graffiti, and the potties that have been thrown aside are still full of human waste. The smell of urine is all at once unbearable, so I turn and plead to be allowed to see a superior officer. The screw says nothing, just walks out, slamming the door behind him. I spend the rest of the morning standing up against the door, too disgusted by the squalor to touch or go near anything.

DECEMBER 28, 1984

I find it hard to believe, but things get worse as soon as I wake up. An officer comes into my cell and informs me that I am no longer the gym orderly. I have been assigned to Workshop No. 3, which means I shall be sewing buttons on army uniforms. I have also taken a pay cut to £1 per week. The reason for this is that the Home Office has instructed the prison authorities that I am a security risk and likely to try to escape.

The workshop is a long, rectangular room with gray walls, overhead fluorescent lights, and sewing machines screwed onto wooden benches. About one hundred inmates are assigned to this particular shop. A supervisor shows me how to work the machine, gives me some jackets, and tells me the quota I need to hand in during the three-hour morning session. After a couple of hours I am hopelessly behind.

DECEMBER 29, 1984

During slop-out this morning, I hear that a man has hung himself in his cell. Apparently, the suicide was facing forty years for murder and drug dealing, and took the easy way out. On remand, when prisoners are allowed to wear their own clothes, he used his belt to hang himself.

Later I learn that the screws have sometimes leaked false information to inmates they dislike, such as the death of a loved one, or impending divorce, and prisoners have been known to hang themselves as a result.

DECEMBER 31, 1984

The last day of a disastrous year. It dawns in typical fashion—gray, gloomy, wet, depressing. After three weeks of trying, I am the first to reach the loo and slop out this morning. It is a good omen, I am told. I'm not so sure, however, because just as I am in the process of slopping out, a rat jumps from the wastebin and disappears among the rushing inmates.

After breakfast I go to see Mr. Wrigley—who by now thinks I'm a con man because of the Home Office instructions—and ask permission to go to Landing No. 1 and say good-bye to Sid. The old boy is getting out today, although, as Mr. Wrigley tells me, he should be back in a month or two, since poor Sid has no family other than the prisoners. "Send the Rolls for me and we'll have lunch at the Ritz," he says in bidding me good-bye, and I feel as if I'm losing my closest friend. Which I am.

An older Pakistani man who sits two benches down in the workshop tells me a funny story during a cigarette break in the bathroom. A professional pickpocket, he was working the Regent Palace Hotel in Piccadilly when he picked up a briefcase from a man paying his bill, and disappeared \yith it into Hyde Park. Once in the park, he opened it up and found a bomb ticking away. He raced off and was almost immediately tackled by Special Branch detectives who had been following him ever since he had picked it up. They thought it was a transfer between conspirators. He had spent three months sticking to his story, and then another six waiting for trial. He got two years. If his story is true, he's the unluckiest pickpocket in London.

The supervisor is complaining about my lack of output, and I tell him that I have no experience with machines. "You're the worst I've ever seen," he tells me, and I can't help asking him if Oscar Wilde (who spent almost a month in Pentonville) was any better. "If you think I keep records of who comes in here, you're mistaken," he answers.

JANUARY 26, 1985

On my way to the gym this morning I dropped a piece of paper near the garbage can rather than in it, and a screw named Scanlon yelled at me to "retrieve that at once!" Scanlon has a vile reputation with the cons. He is one screw who likes being a screw and throwing his weight around, so I tried to pull his leg a bit and asked him where in the world he had learned such a long word as "retrieve."

Well, I've been warned about being sarcastic with the guards. I should have listened. No sooner did I open my big mouth than Scanlon—a huge man—was on me, grabbing me by the back of my neck and forcing my head down to the floor, shouting insults and threatening me with the block. Although I felt deeply mortified, I said nothing and did even less. Guards are known to fake taking a shot in the gut, and "retaliate" by sending the prisoner to the block for the maximum two weeks.

Once he had let go of me, I threw the paper inside the can and began to walk away, but he came at me again and ordered me to stand at attention facing the wall. In the meantime, all the cons on their way to work stared at the spectacle. I swallowed hard, but followed Scanlon's orders to the letter.

After about an hour, I was summoned to the gym. The other inmates there accused me in no uncertain terms of being a coward, of playing footsie with the enemy. I got furious and told them to go and fuck themselves, but I felt ashamed and terribly humiliated.

FEBRUARY 25, 1985

Eddie Hayes, an American lawyer friend of mine, has come to visit. Lawyers do not have to be invited and can drop in at will. But Eddie has flown over for an express purpose. I have asked him, through Alexandra, to sneak out my diary, which I have continued keeping by writing between the lines of the letters I've received. During cell searches, the screws have not even come close to looking inside the envelopes, but I'm getting nervous that they might, especially as Scanlon has it in for me.

We embrace and he leaves with my diary safely inside his shoe. When I tell him there is no search for lawyers, he says he's Irish, so in his case they may make an exception. I go back to the gym feeling relieved and happy.

Days are getting longer and longer, literally. When I look out my tiny cell window, I can still see the gray sky at teatime, 4:30 P.M. It feels much like the end of a school term. Gate fever getting worse and worse.

FEBRUARY 27, 1985

This may sound like a Hollywood ending, but my hunch to send out the diary was certainly lucky. Just after gym this morning, the assistant governor called me in and told me that I will be released early for good behavior. Perhaps as early as tomorrow.

When you hear such news in prison, the reaction is the same as when you were sentenced to go there. In an instant your whole life flashes by. Incredibly, I feel a sense of sadness. Of guilt. As if release will mean trouble.

I say nothing to my mates, because, frankly, I'm too ashamed. I'm getting out and they're staying behind. I make two exceptions: Warren, a Rastafarian friend from the workshop, and Pavlo, the Greek Cypriot. I'm going to leave them my extra clothes, the stuff I stole from the gym, things like extra shirts and socks, and also a radio, my watch, soap, toothpaste, food, and four joints that were given to me by Tony the Loon long ago.

FEBRUARY 28, 1985

Just before six A.M., I hear the one jingle of keys I've been waiting to hear since December 14 of last year. As I pass Pavlo's and Warren's cells, I sense them up and listening. I knock. "Good luck, have fun!" they yell back. They were wideawake. It is hard to feel happy under the circumstances.

Once in the processing room, I am given my gray single-breasted suit, my black shoes, striped tie, blue shirt, signet ring, and £50, courtesy of Her Majesty, and told to step right out as a free man. One of my favorite guards, Mr. Gordon, is waiting in the yard, and he takes me to a side entrance. He opens the door, looks out, and waves me on. It is 7:33 A.M. and I am free.

With the first whiff of freedom came an attack of paranoia. I felt sure that people in the street were looking at me. I window-shopped and walked slowly down the Caledonian Road. I wasn't keen to go home right away. I wanted to savor the feeling of being free to do as I pleased. But the gloom persisted.

Not for long. Suddenly a taxi screeched to a halt and two friendly faces appeared at the window. Next came two hands, beckoning me in. Then the window lowered and out floated two voices. "Come on, hop in. We know you've been out all night..." It was Michael Medwin, a film producer and a fellow member of the Turf Club, and the actor Albert Finney. Neither of them had a clue as to where I'd been, but when I told them, they grew even more convivial and insisted I go with them for a drink. I declined. Their attitude, however, cheered me no end. Eventually I hailed a cab and went home.

It is strange, but even Hollywood gets it right on this point. You don't go for the bright lights on the first night out of jail. On the contrary, when some friends rang up to invite me to a party the next day, I feigned illness. I was much too embarrassed to be seen living it up, especially in merry old England. The next morning, Alexandra and I flew to Switzerland, where the children were waiting for us in Gstaad. The news had gotten out and the staff of the Palace Hotel lined up in the lobby and greeted me like the conquering hero I wasn't. I was very moved.

That evening Bill Buckley and his son, Christopher, gave a large dinner party intended to welcome me back to the lawful world. At the last minute I got cold feet and phoned Christopher, who, along with being one of my closest friends, was also my best man when I married Alexandra. He dismissed my fears by reminding me that I would be among people who liked me. "Besides," he added, "having cavorted so brazenly in nightclubs just before you went in, it is ludicrous to be ashamed now that you have paid your debt to society." Then he went on to tell me with his typical facetious wit "how eager we all are to meet someone who has been the guest of the Queen of England" for several months.

Trouble, though, seemed to be stalking me. As soon as I arrived at the Chateau de Rqugemont, the Buckley winter abode, a weird accident happened. Roger Moore, the actor and longtime Gstaad resident, walked smack into a lintel and knocked himself out cold. Later I heard that he had just turned to tell his wife to cool it—she was saying something about prison, a taboo subject for that evening—and thus failed to see the low beam before him. So, while first aid was being hurriedly administered to James Bond, I slipped into the room without fanfare. Christopher was convinced I had done a "dirty" on poor Roger: "One of your new prison tricks, I suppose."

The group Bill had assembled did not exactly resemble the crowd I'd left back at Pentonville. John Kenneth Galbraith, Alistair Home, Prince Romanov, Bamaby Conrad III, Sam Vaughan, and an assortment of Scandinavian royalty. Professor Galbraith was among the first to engage me in conversation, something he had not often initiated in the twenty-odd years I'd known him. Later on in the evening, Bill told me how Galbraith had recently done more for me than simply start our idle chitchat that night.

Among the things I'd neglected to do before my trial was to resign from the Eagle ski club. The truth is, I plumb forgot, especially since I have always thought of the Eagle as a glorified place to lunch, not as a gentlemen's club. So, while I was elsewhere, paying my debt to society, a Belgian multimillionaire, Louis Franck—since deceased—began a movement to drop me as a member. Although his efforts came to naught, a letter sent in response on my behalf from the good professor did cause an uproar. Galbraith, who has consistently refused to join the Eagle, wrote that "since half of the membership of the club belongs behind bars, it is unfair to pick on Taki.''

Still, despite the congenial atmosphere and the marvelous Buckley wine, the old spark wasn't there. I was nevertheless extremely grateful to Bill for his show of solidarity when I most needed it.

I stayed in Gstaad for a while, spending time with the children, but even there I felt awkward. My wife had doubts about whether our marriage could survive, and my little girl was suspicious about where I'd been—she's smart and the invented job in Australia hadn't convinced her— and finally I had Alexandra tell her the truth. I wasn't brave enough. When I returned to London, I stayed away from the bright lights and saw only close friends such as John and Aliki Goulandris, Harry Worcester, and Oliver Gilmour.

After a few months, Alexandra decided to stay with me, the devil she already knew so well, and we have remained close and happy ever since. My mentor, Ernest Van Den Haag, had a lot to do with my redemption. His advice was simple. "If you do it, don't brag about it" was all he said, and, as always, he turned out to be correct.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now